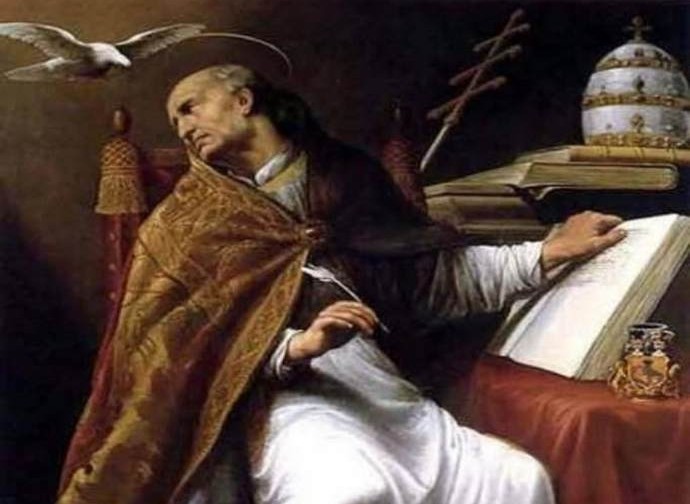

Saint Gregory the Great

While Italy was going through one of the darkest periods of its history, beset by famine and substantial anarchy, the figure of Saint Gregory I (540-604), known as ‘the Great’, was a beacon of light. In the 14 years of his pontificate he carried out a profound moral reform of the Church and played a decisive role as peacemaker in the most dramatic phase of the Lombard invasion.

While Italy was going through one of the darkest periods of its history, beset by famine and substantial anarchy, the figure of Saint Gregory I (540-604), known as ‘the Great’, was a beacon of light. In the 14 years of his pontificate he carried out a profound moral reform of the Church and played a decisive role as peacemaker in the most dramatic phase of the Lombard invasion.

His frail body contained the soul of a true child of light, with an immense faith in Providence. “He was a man immersed in God: the desire for God was always alive in the depths of his soul and for this very reason he was always very close to his neighbour, to the needs of the people of his time. In a disastrous, indeed desperate time, he was able to create peace and give hope. This man of God shows us where the true sources of peace are, where true hope comes from and thus becomes a guide for us today,” said Benedict XVI in a catechesis dedicated to the saint.

Born in Rome, he belonged to the noble gens Anicia (as did St Benedict, of whom he wrote a famous Life) and was the son of Gordianus and St Silvia. Following in his father’s footsteps he embarked on an administrative career and around the age of 32 he became prefect of the city, maturing that sense of order and discipline which he would later transmit to the bishops. It was in this period that he felt the call of Our Lord very strongly. He left all civil office and retired to monastic life in his house on the Caelian Hill in Rome, which he transformed into a Benedictine monastery, named after St Andrew. His years as a monk were spiritually very rich and he lived in contemplation and fasting, studying the Holy Scriptures and the Fathers of the Church. In 579 he was sent by Pope Pelagius II as apocrisary to the court of Constantinople, where he stayed six years to seek help against the Lombard threat.

In the winter at the beginning of 590 a plague epidemic claimed among its victims the Pope, who died on 7 February. In the meantime, Gregory, who had returned to his beloved monastic contemplation, was called to the throne of Peter by the heartfelt insistence of the clergy, the people, and the Senate of Rome. His consecration took place on 3 September (the day of his liturgical feast). He immediately faced the Lombard question with great lucidity despite the inertia and obstacles posed by the Byzantines, based in Ravenna. Using up his own assets he convinced King Agilulf to liberate Rome from the siege. With holy perseverance - thanks also to the good relations established with Queen Theodolinde - he managed to favour the armistice between the Lombards and the Byzantines, pacifying the peninsula and starting the conversion of the former to Catholicism.

In the meantime he had taken care of the aqueducts, implemented an agrarian reform and distributed grain to the needy, especially in Sicily, where his estates were transformed into several monasteries. His indispensable attention to political problems, in that era of desolation, did not therefore divert him from the preeminent care for the Church, eager as he was to lead as many souls as possible to Christ. Under his pontificate the Visigoths of Spain converted from Arianism. Furthermore, in 597, it was Gregory who sent about forty Benedictine monks, led by the one who would become known as St Augustine of Canterbury, to re-evangelise England. He also availed himself of the Benedictines for the reform of the Curia, entrusting them with many tasks in place of unworthy clerics. Humble and determined at the same time, he contested the title of “Ecumenical Patriarch” arrogantly assumed by the Patriarch of Constantinople (John IV) and, remaining unheeded, introduced the new papal title of “servant of the servants of God”.

He promoted that form of liturgical chant that became known as “Gregorian”. He taught that the active ministerium is born of contemplation, without which it is not even possible to imagine the care of souls. He called this care “the art of the arts” and explained that the shepherd can fulfil his very high task only if he recognises his own deficiency and entrusts himself totally to God. With this same attitude of listening to the divine will he wrote the Homilies on the Gospels, the Dialogues, the Pastoral Rule, and his main work, Moralia in Job, an exegesis of the Book of Job, which in the Middle Ages was considered “a kind of Summa of Christian morality” (Benedict XVI).

We are also left with an epistolary of 848 letters, a precious source for understanding his era and a mine of advice and teachings. “What is Sacred Scripture if not a letter from God Almighty to his creature?”, he wrote for example to a man of many talents, but who had lost himself in worldly things: “The Lord of men and of angels has sent you letters concerning your life [...]; learn to discover God’s heart in God’s words, so that you may attend to eternal things with greater ardour”. One of the first four Doctors of the Church (with Augustine, Ambrose and Jerome), he recommended approaching the Sacred Scriptures not with the desire to dominate them (out of pride and a mere thirst for knowledge that could lead to heresy), but as nourishment of the spirit, combining study with prayer.

Patron of: singers, musicians, popes

Learn more:

Catechesis of Benedict XVI (General Audiences of 28 May 2008 and 4 June 2008)