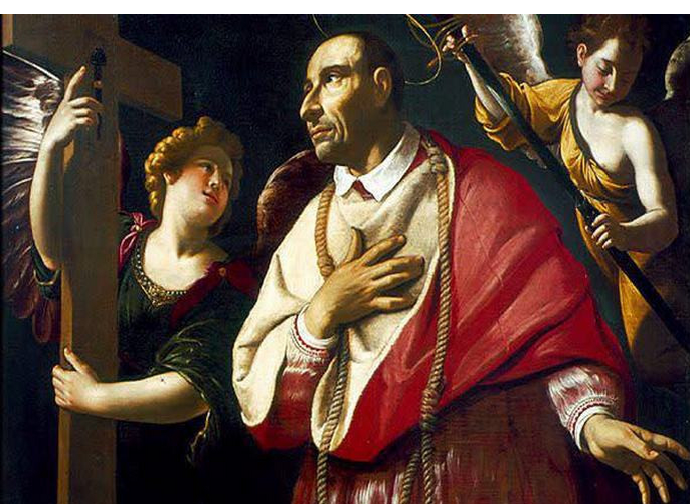

Saint Charles Borromeo

Few people have managed to work tirelessly for the common good and to make an impact on their century and beyond as St. Charles Borromeo (1538-1584). He was rightly called “a second Ambrose” and is considered one of the most shining examples of holiness that animated the Catholic Reformation.

Few people have managed to work tirelessly for the common good and to make an impact on their century and beyond as St. Charles Borromeo (1538-1584). He was rightly called “a second Ambrose” and is considered one of the most shining examples of holiness that animated the Catholic Reformation. He used his family wealth to build hospitals and hospices, personally assisted the plague victims, at the Council of Trent he promoted the establishment of seminaries and defended the faith against Protestant heresies. “Model for the pastors and their flock in recent times”, Pius X called him in the encyclical Editae Saepe of 1910, written for the third centenary of his canonisation, in which he recalled that Saint Charles “was the unwearied advocate and defender of the true Catholic Reformation, opposing those innovators whose purpose was not the restoration, but the effacement and destruction of faith and morals”.

He was born to Count Gilberto and Margherita de' Medici, sister of Pius IV. His was a wealthy family of great faith, from which he received a profound Christian education that helped him to remain humble despite the many responsibilities he was given since he was a child. At the age of 12 he was appointed commendatory abbot of the Abbey of San Leonardo and decided to donate the entire income to the poor. Shortly after obtaining a degree in utroque iure, the newly elected Pius IV wanted him in Rome and appointed him cardinal-deacon at only 21 years of age. The Pontiff was soon impressed by the turn to asceticism of his nephew, who at the sudden death of his brother Federico reacted by abandoning himself totally to God, intensifying his fasting and penance. His life of renunciation was matched with a fundamental trait: he was a man of action, brilliant and without respite, to the point that someone of the standing of Saint Philip Neri said of him: “But this man is made of iron!”.

He positively exercised his influence to reopen the Council of Trent, in which he played the leading role. Not only did he obtain the establishment of seminaries for the training of priests, but he also dealt with other primary issues: he defended Catholic doctrine on the sacrificial character of the Mass, he was president of the commission of theologians in charge of writing the Roman Catechism, he worked on the revision of the Missal and the Breviary and took an interest in the sacred music to be used during the liturgy. When Pius IV died, he could have succeeded him on the Petrine throne, but he preferred to support the Dominican Michele Ghislieri, who became pope under the name of Pius V and favoured the application of the Tridentine decrees.

Saint Charles implemented the decisions of the Council of Trent in his capacity as Archbishop of Milan, a diocese that at that time extended over Swiss, Venetian and Genoese territories and which had been lacking a resident archbishop for eighty years. The saint instead travelled the length and breadth of the diocese, restored discipline in the clergy, ordered parish priests to keep up-to-date records, revived the faith of the people with collective prayers and processions. His reputation for holiness reached its peak during the plague of 1576-77: while the governor and the grand chancellor were leaving the city, he returned there (he had been away on a pastoral visit) to help the sick and organised a procession with the relic of the Holy Nail to calm the epidemic.

He was beloved by the common people, but his work of reform and the defence of the clergy from the interference of the powerful did not please everyone. He suffered aggression from some religious and even a failed attack on his life, in which a friar of the Humiliati - an order later suppressed because of its Protestant tendencies - shot him in the back while he was praying. He died at the age of 46, exhausted by illness, pastoral activity and penance, after having witnessed with his life the inseparable union between faith and works that Luther denied: “Good works are the basis of prayer; take them away, and not even prayer lasts”.

Patron of: catechists, bishops; Lombardy