War on Traditional Latin Mass: it wasn't the bishops who started it

The desire of the episcopate, invoked by Francis to ‘put an end’ to the Latin Mass, appears quite different according to the documents examined in La liturgia non è uno spettacolo (The Liturgy is Not a Show). No one wanted a war, explains co-author Monsignor Bux; on the contrary, the Church needs liturgical peace.

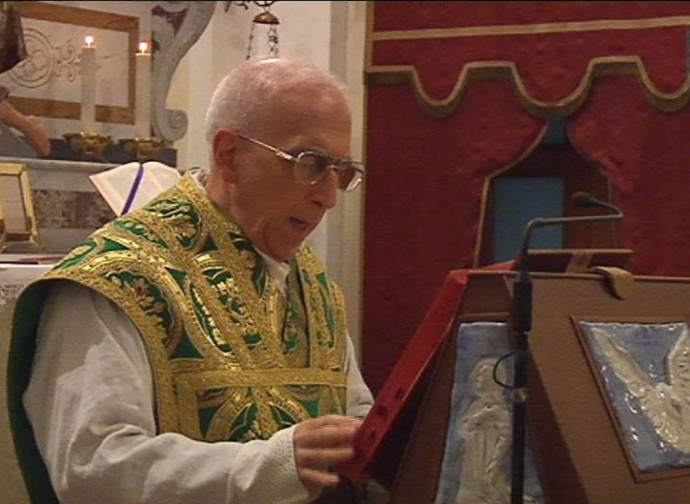

It was not the world episcopate that asked to ‘cage’ the Mass in the ancient rite, as Pope Francis claimed when he declared that the motu proprio Traditionis Custodes was the response to a specific request from the bishops consulted on the matter. A scoop by journalist Diane Montagna, however, shows, with documents in hand, a very different reality about that consultation: no one asked for the total abolition of Benedict XVI's Summorum Pontificum (which had opened those doors then abruptly closed by Francis), nor for the total disappearance of the ancient liturgy (the explicit goal of Traditionis Custodes). Monsignor Nicola Bux and Saverio Gaeta, co-authors of the book La liturgia non è uno spettacolo. Il questionario ai vescovi sul rito antico, arma di distruzione di Messa (Fede&Cultura, Verona 2025), also shed light on the documentation. Monsignor Bux, interviewed by La Bussola, places the controversial genesis and repercussions of Traditionis Custodes in the broad horizon of the ‘liturgical peace’ hoped for at the time by Benedict XVI and dramatically interrupted in 2021.

So, Monsignor Bux, it was not the majority of bishops who pushed to ‘do away’ with the traditional Mass?

The first to be surprised was Pope Benedict, as we know from Monsignor Gänswein's book, Nothing but the Truth. But it was also surprising to many others that the bishops of the world took such a negative stance towards an act – Summorum Pontificum – that had effectively restored liturgical peace, as desired by Benedict XVI himself, and at the same time had done justice to a precious and millennial heritage. Among other things, it is not clear why tradition is being rediscovered everywhere, even in the culinary sphere (the ‘traditional cuisine’), but this should not apply to the liturgy. Not to mention the great heritage of Eastern rites, recently highlighted by Leo XIV.

The measures of Traditionis Custodes were also justified by pointing to alleged anti-ecclesial attitudes. Yet, reading the bishops' responses, one gets the impression that these are limited cases and not such as to call for the abolition of Summorum Pontificum...

It is always difficult to analyse the meaning of the Church and the faith of the people. One could then also analyse all the people who attend the ordinary Mass: whether they have a sense of the Church, whether they feel united with the Church on the truths of faith and morals. We know very well that this is not the case. Therefore, attributing a distorted sensus Ecclesiae to the extraordinary rite is not correct. There has been dissent from all sides, even in progressive circles (think of the Dutch Catechism), but that is not a good reason to keep people out of the Church.

In the questionnaire, some bishops acknowledge the positive effects of the ancient rite even for those who celebrate the new one. But then, wouldn't banning it be a loss for everyone, not just for this or that group?

Certainly. If the ordinary form or Novus Ordo – which its proponents present as a development of the ancient form – has undergone, as we know, ‘deformations to the point of being almost unbearable’ (Benedict XVI, 7 July 2007), this clearly means that it needed that restoration of the sense of mystery that is very present in the Eastern liturgies (as Pope Leo reminded us) and that is equally present in the ancient rite. Even the Orthodox, who sometimes participate in the so-called extraordinary rite or Vetus Ordo, are struck by it. As a scholar of Byzantine liturgy, I can say that if there is a rite very similar to the Byzantine rite, it is the ancient Roman rite. So why sever a relationship that, among other things, is also very beneficial for encounters with Eastern Christians? I would just like to recall that when the motu proprio Summorum Pontificum was issued, the then Patriarch of Moscow, Alexy II, congratulated Pope Benedict because he said that only by recovering our common roots, traditions and liturgies will Christians come closer together.

What have been the effects of Traditionis Custodes to date?

I believe that overall the effect has not been that impressive. Of course, the obedience that must characterise bishops and priests has obviously slowed down the celebration of the ancient Roman rite, but it is unlikely to stop it. The reality of traditio is like the water of a river that grows richer as it flows. But if we reject this richness of faith, prayer and liturgy that we have received, how can we expect the new generations to draw closer to the Catholic Church? Let us look instead at the young people who take part in traditional pilgrimages, such as Paris-Chartres or Covadonga in Spain, and others that are being planned. The hope is that the ideology that tends to cling to ecclesiology and liturgy will be abandoned once and for all, because the Church is always a reality that comes from above, the heavenly Jerusalem that descends among us, not something that is “made”. Pope Benedict insisted on this point: the liturgy is not the result of the arbitrary will of priests or bishops, nor even of the Pope and the Apostolic See. For even the Pope is subject to the Word of God and therefore to the tradition that this Word has handed down to the present generation over two millennia.

Is this why the book opens with an excursus on the Mass throughout the centuries?

Exactly, it is to demonstrate – with a necessarily concise excursus – that what we profess comes from the apostolic tradition, not from someone's inventiveness. In the book, we wanted to place the question of the questionnaire's assessments in its proper context and then conclude with recent events, from Summorum Pontificum to Traditionis Custodes, and then make an appeal to the Pope.

It is too early to say how Leo XIV will proceed, but what can we hope for the future of “liturgical peace”?

We need to get back on the path of the “reform of the reform”, in the sense that Benedict XVI understood it, starting from the observation that the liturgical reform has not really taken off, or has flown very low, to the point that it has allowed deformations, arbitrariness, Masses on mats and so on. This is because it was not “armoured” by canonical norms and sanctions, despite Sacrosanctum Concilium being very clear on this point, warning that no one, “even if a priest, should dare, on his own initiative, to add, remove or change anything in matters of the liturgy” (22,3). Let us ask ourselves what has happened instead in these sixty years and let us resume studying how it went. I make a proposal directly to the Pope and to the Prefect of the Congregation for Divine Worship: let us have the courage to study the documents of the Consilium established by Paul VI for the implementation of the liturgical reform, or the Memoirs of Louis Bouyer, one of the great experts who participated in it... let us have the courage to seek the truth.

And then to recover, not through imposition but with the patience of charity, what has been left on the ground, to graft back the severed branches, to use an Augustinian image. This is the work that I would call ‘reform of the reform,’ without ideological pretensions but as a fact, a respectful confrontation, which certainly cannot happen overnight. In the meantime, let us allow the two ritual forms to “ferment” – as most of the bishops said in their responses to the questionnaire and as hoped for by Summorum Pontificum.

If Jesus speaks of the wise scribe who draws from his treasure nova et vetera, new things and old things, it is not clear why we should not be able to do the same with the great traditional heritage of the liturgy.