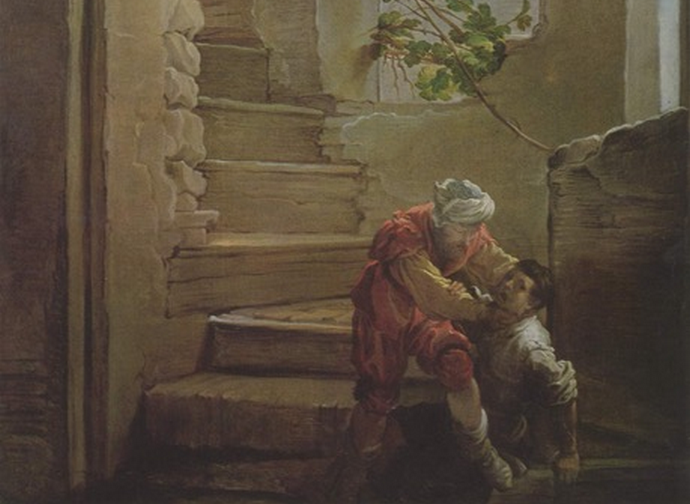

The unmerciful servant in a painting by Fetti

Among the 42 parables of the Gospels, one of the most interesting is that of the unmerciful servant, because it tells us about two different ways of using power. On the one hand divine grace, on the other an ungrateful man. The scene of the servant throtting one of his small debtors is depicted in all its intensity in a painting by Domenico Fetti, known as ‘il Mantovano’.

The parables (from the Greek παραϐολή, parable) of the New Testament are mainly found in the three synoptic Gospels. They are allegorical stories told by Jesus of Nazareth and present moral and religious teaching. Following a process rooted in Jewish tradition, these stories aim to present truths through elements of daily life or observation of nature, but with Jesus they move away from the rabbis’ merely pedagogical form of interpretation of the Law, to evoke the Kingdom of God and the changes that take place at the time of His coming.

There are 42 parables, of which eleven are common to the three synoptic Gospels, eight to two Gospels, one is found exclusively in Mark's Gospel, six only in Matthew's, thirteen in Luke's and three in John's Gospel.

One of the most interesting parables, in this writer's opinion, is that of the unmerciful servant (Matthew 18:21-35) because it speaks of the use of power.

Then Peter went up to him and said, 'Lord, how often must I forgive my brother if he wrongs me? As often as seven times?'Jesus answered, 'Not seven, I tell you, but seventy-seven times. 'And so the kingdom of Heaven may be compared to a king who decided to settle his accounts with his servants. When the reckoning began, they brought him a man who owed ten thousand talents; he had no means of paying, so his master gave orders that he should be sold, together with his wife and children and all his possessions, to meet the debt. At this, the servant threw himself down at his master's feet, with the words, "Be patient with me and I will pay the whole sum."

And the servant's master felt so sorry for him that he let him go and cancelled the debt. Now as this servant went out, he happened to meet a fellow-servant who owed him one hundred denarii; and he seized him by the throat and began to throttle him, saying, "Pay what you owe me." His fellow-servant fell at his feet and appealed to him, saying, "Be patient with me and I will pay you." But the other would not agree; on the contrary, he had him thrown into prison till he should pay the debt. His fellow-servants were deeply distressed when they saw what had happened, and they went to their master and reported the whole affair to him.Then the master sent for the man and said to him, "You wicked servant, I cancelled all that debt of yours when you appealed to me. Were you not bound, then, to have pity on your fellow-servant just as I had pity on you?" And in his anger the master handed him over to the torturers till he should pay all his debt. And that is how my heavenly Father will deal with you unless you each forgive your brother from your heart.

How to explain that a servant owed his king ten thousand talents? What king would have lent such an exorbitant sum to one of his slaves? It is hard to believe, unless these 'servants' were vassals of the king or lords or governors responsible for the administration of a district of his kingdom. Perhaps it is better not to look for an answer to these questions. Jesus needed the sum to be huge for the purposes of his parable. The "talent" represented a certain weight in silver or gold that varied from country to country. In Greece it was equivalent to 6,000 denarii, or 6,000 times the daily wage of an agricultural worker (Matthew 20:2). Ten thousand talents thus represented 600,000 times the debt of the second debtor: it is this disproportion that matters in the parable.

The servant, of course, could not pay such an enormous debt. The king therefore decided to sell him as a slave, together with his entire family. This was also a common practice in Israel (Leviticus 25:39-47; 2 Kings 4:1; Nehemiah 5:5; Isaiah 50:1; Amos 2:6; 8:6). This king is not a tyrant, he acts according to the customs of the time. He is simply righteous. The servant is an illustration of man's enormous spiritual debt, of his total decline. He has nothing with which to repay, to atone for his sins. God holds man responsible for his sins and imputes them to him. Therefore he is enslaved by his sins.

And here the grace of God, who is all-powerful, intervenes. He decides to wipe clean the slate of this unfortunate man's sins and cancels his debt. One would expect much gratitude from the servant. Not only does he show none, but as soon as his debts (read: sins) are wiped away, he thinks about committing new ones. And so he enters the downward spiral of the evil use of power. This is a subject that, unfortunately, is little explored by schools, families, and even the Church. Perhaps because the notion of power has been simplified by linking it to evil: power = evil, badly used. But this is not the case, and this parable shows us so: the first debtor benefits from the good use of power (compassion, mercy), while the second is the victim of the bad use of power (cruelty, impiety). Although he had just been forgiven, the wicked servant is himself incapable of forgiving.

This is something we also observe in our everyday lives: there are people who feel so unworthy of God's goodness that they do not contemplate forgiveness either for themselves or for others (this is the main reason why many do not go to Confession). They are so deeply sunk in sin as a reoccurring action that they consider forgiveness useless. We can deduce that the wicked servant is incapable of forgiveness because he himself lacks the capacity to be forgiven, unconsciously thinking that he does not deserve it. In fact, to the inflexibility of the attitude is also added violence, because, let us not forget, the wicked servant, on meeting his debtor, grabbed hold of him by the throat and “began to throttle him”.

The terrible scene is skilfully depicted by an Italian artist who is little known to most, but whose works can be found in a large number of museums around the world. The work is Parable of the Unmerciful Servant, painted in 1620 and exhibited in the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister (Old Masters Gallery) in Dresden. The artist is Domenico Fetti (Rome, 1589 - Venice, 16 April 1623), or Feti, also known as 'il Mantovano'. He was an Italian painter well known in the Baroque era for the extraordinary naturalistic vein of his works. He was very prolific, despite his rather short life. He was born in Rome in 1589 and served his apprenticeship under Lodovico Cigoli (1559-1613). In 1614 he moved to Mantua where he was employed by the Gonzagas as court painter, thanks to Grand Duke Ferdinand who made his paintings famous. This period gave him the nickname 'il Mantovano' (the Mantuan).

The terrible scene is skilfully depicted by an Italian artist who is little known to most, but whose works can be found in a large number of museums around the world. The work is Parable of the Unmerciful Servant, painted in 1620 and exhibited in the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister (Old Masters Gallery) in Dresden. The artist is Domenico Fetti (Rome, 1589 - Venice, 16 April 1623), or Feti, also known as 'il Mantovano'. He was an Italian painter well known in the Baroque era for the extraordinary naturalistic vein of his works. He was very prolific, despite his rather short life. He was born in Rome in 1589 and served his apprenticeship under Lodovico Cigoli (1559-1613). In 1614 he moved to Mantua where he was employed by the Gonzagas as court painter, thanks to Grand Duke Ferdinand who made his paintings famous. This period gave him the nickname 'il Mantovano' (the Mantuan).

In Mantua he managed to get together the money needed to open his own workshop, where his family also worked. In this city, Fetti was able to devote himself to frescoes and oil paintings, which are among his most famous paintings, commissioned mainly by local churches: These include the Apotheosis of the Redemption, in the apse of St. Peter's Cathedral; the Multiplication of the Loaves and the Fishes (where types of commoners, old people, children, men and women, re-emerge from the poor and pompous 17th-century crowd), various paintings of Martyrs, and other paintings created for the church of Sant'Orsola and now kept in the Ducal Palace in Mantua. These were not the only famous paintings that caught the attention of the Mantuans; those on the Gospel parables (the Blind Leading the Blind, the Good Samaritan, and the Prodigal Son, as well as the Unmerciful Servant) are also worth mentioning.

The artist's role models were Giulio Romano, Caravaggio, and Rubens, who inspired his painting, which featured luminous contrasts, intense colours and rough brushstrokes. In 1622 Fetti left for Venice, where, fascinated by the city, he decided to stay. Unfortunately it was not for long: the following year he died of an illness. From his Venetian period, we have the three scenes of the Passion of Christ in the Corsini Gallery in Rome. Also worth mentioning is Melancholy (c. 1618) on display at present in Paris (in the Louvre): it is a work of profound inspiration.

The artist's role models were Giulio Romano, Caravaggio, and Rubens, who inspired his painting, which featured luminous contrasts, intense colours and rough brushstrokes. In 1622 Fetti left for Venice, where, fascinated by the city, he decided to stay. Unfortunately it was not for long: the following year he died of an illness. From his Venetian period, we have the three scenes of the Passion of Christ in the Corsini Gallery in Rome. Also worth mentioning is Melancholy (c. 1618) on display at present in Paris (in the Louvre): it is a work of profound inspiration.

But the intensity of the painting depicting the unmerciful servant is more striking than all the others and makes one think. For there is no sin worse than the sin against God's grace.