St Patrick's Purgatory: A Preview of Dante's Journey

St Patrick, the patron saint of Ireland, is associated with a mysterious place where anyone who entered would emerge purified after contemplating the joys of the blessed and the pains of the damned. This place became a popular pilgrimage destination and a source of literary inspiration, as seen in the tales of the knight Owein and Dante's Divine Comedy.

Saint Patrick, the patron saint and apostle of Ireland, is one of the most fascinating figures of early Christianity. Born in Roman Britain around 385 AD, he was the son of a Christian and Romanised family. He soon experienced the harshness of life when, at the age of sixteen, he was kidnapped by Irish pirates and sold as a slave in the north of the country. There, amid lonely pastures and unfamiliar languages, he developed a profound faith and a profound insight: the people who held him captive were not crude or barbaric, but rather possessed a tribal dignity and a sense of the sacred that impressed him.

After six years of servitude, he escaped and returned to his homeland, where he had a dream in which he heard the Irish calling his name. He interpreted this as a vocation. He trained in Gaul under the guidance of St Germanus of Auxerre, embraced monastic life on the island of Lérins, and studied the missionary methods of Italian monks. Finally, he was consecrated as a bishop to succeed Palladius in the work of evangelising Ireland.

With intelligence and courage, he won the trust of local kings, introduced monasticism, founded dioceses, and trained a native clergy. He faced the hostility of the Druids and the slander of the Pelagians. He died in 461, leaving behind a profoundly transformed island and a memory destined to become legendary. It is in this context of faith, visions and conversions that the most mysterious story associated with him was born: St Patrick's Purgatory.

This secret doorway to the afterlife was said to have been revealed to St Patrick by Christ himself, and according to tradition, it was located in a hidden cave in a deserted place in Ireland. Anyone with the courage to enter it for a day and a night, animated by a genuine spirit of penance, could witness the suffering of the wicked and the bliss of the righteous with their own eyes, returning to Earth purified. St Patrick had a church and a wall built around this mysterious threshold, with a door guarded by the prior. This became a place of pilgrimage, fear and hope, attracting crowds of penitents and generating stories that were to circulate for centuries.

Sir Owein: A Journey Between Vision and Penance

The most famous of these tales is that of Sir Owein, the protagonist of the Tractatus de Purgatorio Sancti Patricii, which was composed by H. de Saltrey. The author places the adventure in the time of King Stephen, while Matthew of Paris dates it to 1153. Owein recounted his experience to the Cistercian monk Gilbert of Luda, who in turn passed it on to Saltrey — a chain of voices that has allowed the legend to reach us today.

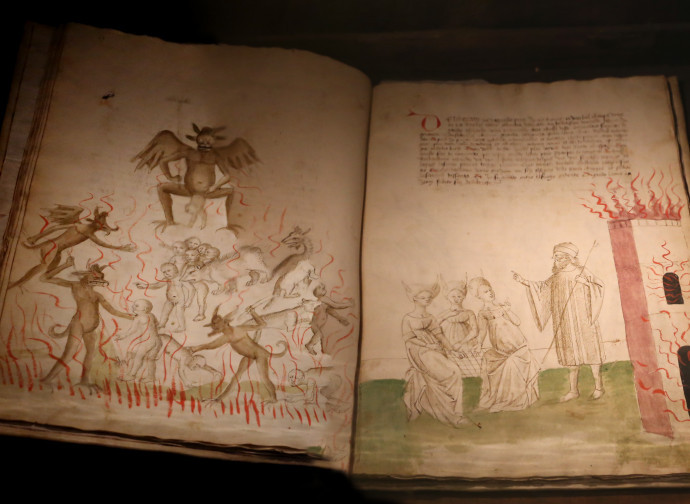

Burdened with sins and determined to redeem himself, Owein approaches the trial as a knightly endeavour. The demons immediately try to burn him at the stake, but fail. The knight then crosses a dark and desolate moor, lashed by a wind that seems to pierce his body — a prelude to the terrible visions that await him. His journey winds through a sequence of places of torment, striking for the power of their imagery, and surprisingly similar to certain episodes in Dante's Divine Comedy.

The Fields of Punishment

In the first field, Owein sees naked men and women lying on the ground with their hands and feet nailed down by burning nails. They cry out, 'Parce!' and 'Miserere!', lamenting their fate. The violent against God in Dante's Inferno come to mind, lying on burning sand, as do the hypocrites crucified in Bolgia XXIII: the posture of the bodies, the crying and the tongue loosened by pain seem to resonate from one text to another, as does the vocabulary.

In the second field, souls lie supine or prone, entwined by snakes, toads, and dragons that sink fiery spikes into their hearts. This scene closely resembles the bolgia of thieves (Inferno XXIV–XXV), where snakes bite, squeeze and pierce and where souls undergo painful metamorphoses.

The third field shows men and women pierced by nails all over their bodies and flogged by demons. The fourth field is a realm of fire where bodies are suspended from red-hot chains by their hair or arms and roasted, fried and burned by hooks stuck in their eyes and ears. Then a gigantic wheel of fire appears, dragging souls into a whirlwind. When one half rises, the other sinks into underground flames.

One of the most impressive places that follows is a thermal building with boiling pools of liquid metals, into which souls are immersed at different depths: 'up to their eyebrows', 'up to their lips', 'up to their chests' and 'up to their knees'. The anatomical precision with which the Tractatus describes the level of immersion is strikingly similar to Dante's description of the Phlegethon in Inferno XII, where violent individuals are immersed in boiling blood at various depths, from their eyelashes to their feet.

Finally, Owein sees a mountain from which a river of fire descends. At the top, an icy wind blows and plunges the souls into the fiery river. This is reminiscent of Dante's 'astripeto regno', where wind and fire coexist in terrible balance. The final threshold is a well from which a black, foul-smelling flame emerges, into which the souls fall like sparks. The demons warn Owein that this is the true gate of Hell, from which there is no return. There are echoes of Dante here, with surprising images, structures and correspondences.

After experiencing so much horror, the knight arrives at a very high wall with golden doors, and a sweet scent fills the air. This is the Earthly Paradise. A solemn procession of crosses, candles, palms and songs welcomes him. Two ecclesiastical figures guide him to a mountain, where he can see a burning door — the entrance to Heaven. A flame descends from the sky and touches each person's head — it is the food of God, the eternal nourishment of the blessed. Owein would like to stay, but he is not permitted to do so. Having been purified, he returns, and the demons can no longer touch him. After spending fifteen days in prayer, he leaves for the Crusades. Upon returning to his homeland, he becomes a servant of the monk Gilbert and helps to build an abbey.

The similarities between the Tractatus and the Commedia are not limited to images of punishment. The sequence of torments also presents striking analogies: in the Tractatus, Owein first encounters souls nailed to the ground and then souls attacked by snakes, whereas in the Commedia, Dante first sees hypocrites crucified on the ground (Inferno XXIII) and then thieves wrapped in snakes (Infernos XXIV–XXV). However, the most fascinating point concerns the macro-structure of Purgatory: both afterlives feature a front area, seven places of punishment, and an earthly Paradise with a symbolic procession. Of course, Dante brings about a revolution: he removes Purgatory from the underworld and transforms it into a luminous mountain. He also introduces retribution, the deadly sins, individual psychology, Thomistic theology and the practice of confession.