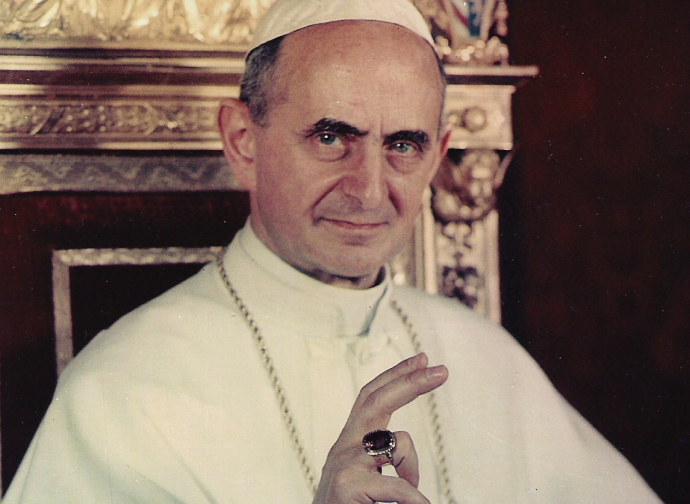

Saint Paul VI to journalists: 'prophets of the word'

An intellectual and a learned man, Pope Montini inherited his love of journalism from his father, equating it with an art and defining it as a ‘courageous mission in the service of truth’.

A lover of words, a fine intellectual and a man of study and prayer. Saint Paul VI (Concesio, 26 September 1897 – Castel Gandolfo, 6 August 1978), whose liturgical memorial is celebrated today, was all of these things. But above all, he was a communicator. This became apparent right from the outset of his pontificate. Five days after his election, his first "outing" as pope was in fact on Vatican Radio on 27 June 1963. Two days later, on 29 June, he held an audience with representatives of the Italian and foreign press. On that occasion, Pope Paul VI recalled his origins as a journalist: "We cannot remain silent about a circumstance that we feel deserves, albeit in a sober manner, a discreet mention: our father, Giorgio Montini, to whom we owe our natural and spiritual lives, was a journalist, among other things. He was a journalist of another era, and worked as an editor for a modest but courageous provincial daily newspaper for many years. If we were to describe the professional conscience and moral virtues that sustained him, we could easily, without being carried away by affection, trace the profile of someone who conceived of the press as a splendid and courageous mission in the service of truth, democracy, progress and the public good.”

Montini's love of words was evident from his time as assistant to the FUCI (the Italian Catholic University Federation), his role as substitute for the Vatican Secretariat of State from 1937 to 1954, and later as archbishop of Milan. During his time as ecclesiastical assistant to the FUCI, he promoted the association's magazines, such as 'Studium' and 'Azione Fucina' (which he himself conceived). During this period, he wrote almost two hundred articles. During his long period of work at the Vatican Secretariat of State, Montini was responsible for overseeing the publication of L'Osservatore Romano. As Archbishop of Milan, he wanted to create two monthly diocesan periodicals. He also devoted much of his time to these publications, publishing numerous articles. As pontiff, his work in the field of communication bore fruit with the motu proprio In fructibus multis of 1964, which saw the creation of the Pontifical Commission for Social Communications. In 1967, Pope Montini established World Communications Day. He also strongly desired the merger of two important Catholic newspapers, L'Italia (published in Milan) and L'Avvenire d'Italia (published in Bologna), which resulted in the creation of Avvenire. The first issue of the new national Catholic newspaper hit Italian newsstands on 4 December 1968.

But let's take a flashback, almost like in a film. Let's go back to the young Montini, the son of a journalist, with his head bent over a typewriter and sheets of paper being filled with words. The year was 1919. At the time, the young Giovan Battista was 22 years old. He had been contributing to the magazine La Fionda for a year. An article dated 2 March 1919 contains a picture of what the editorial office was like and the ideals that inspired the young people who founded the magazine. "We want to be positive people, young people who think; we therefore strive every day to draw from our thoughts and ideas the motivation for our actions. These are the practical applications of our faith. We trace the origins of our initiatives back to the supernatural principle that gives rise to them. Attempts have been made to build without God. Today, countless evils open our eyes". The thinking is crystal clear, as is the prose. The phrase 'young people who think' is particularly interesting, as it refers to writing dictated by thought and reflection. Ultimately, we cannot help but see in this vision one of Montini's favourite authors of the past: St Augustine. This stylistic crossover does not seem far-fetched; it is thought dictating words to the pen. Reflection producing precise phrases.

The value of journalism to Montini is a theme that deserves a separate discussion. Let us try to outline a few key points. A speech that Montini delivered off the cuff to representatives of the foreign press on 28 February 1976 provides the starting point. This remained unpublished until it was included in a small volume entitled Paolo VI, i giornalisti e i geroglifici (Paul VI, journalists and hieroglyphics), edited by Father Sapienza and published by Edizioni Viverein in 2018. Below is the transcript of Pope Paul VI's words. These are concepts that are shockingly relevant today: ‘If we have one observation or desire to express to you, it is this: that you know us in all our complexity and richness, of which we are both heirs and custodians.’ And again: 'You must read us; you must penetrate this little-known alphabet of modern and common culture. We want to be understood deeply, as if deciphering the hieroglyphics of an Egyptian pyramid. If you don't read us, you won't understand what we mean”. This is a clear invitation not only to be journalists in the strict sense of reporting, but also to be investigators of the human soul, or rather, artists. To a certain extent, art and the press were two closely related channels of communication for Montini. In a speech addressed to the foreign press, for example, the Brescian pontiff said: 'Journalists are professionals of the word; they are experts, artists and prophets of the word!'

The impressionistic picture painted so far could only end with a portrait of the pontiff by a journalist. Alberto Cavallari, a veteran journalist of Italy’s most important newspaper, Corriere della Sera, who interviewed Paul VI a few days before he left for New York to deliver his famous speech to the United Nations, wrote, 'I saw a relaxed, spontaneous man who bore little resemblance to the gaunt, tense, introverted, nervous or diplomatic pope he was usually described as. 'We are pleased, you know, to talk about the Vatican,' the Pope said immediately and affably with a witty expression. 'Today, many people are trying to understand and study us.' This is still the case today.'