Eating blood, a taboo broken in the 19th century

For a long time even in Christianity, the heir to Judaism, it was forbidden to eat food containing blood. It was only 150 years ago that foods containing blood began to be tolerated. In fact, Christians neither knew nor practised forms of food deprivation/exclusion for religious purposes.

- THE RECIPE: SEA BREAM WITH DILL AND PINK PEPPERCORNS

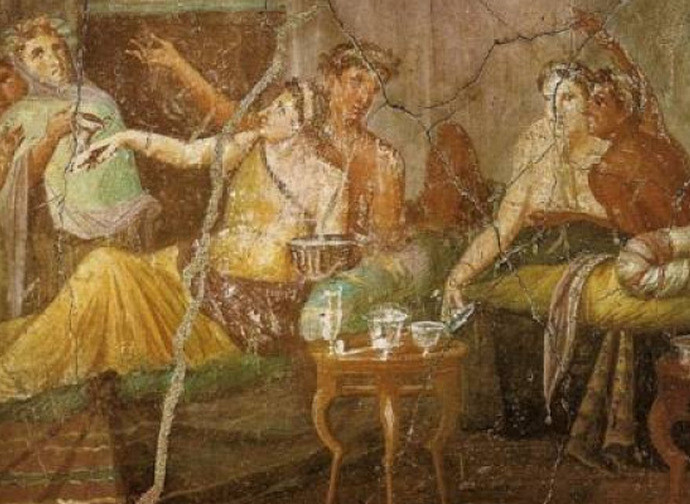

We are in Rome, in the year 57 A.D. In a sumptuous house, two men are having lunch together. They talk about the world, politics, faith. One is dressed in a simple white tunic and wears solid, dusty leather sandals. His thick white beard gives him a hieratic aura. He is the Apostle Peter, invited to share a meal with the Roman centurion Cornelius. Cornelius is elegantly dressed and clean-shaven (the Romans were the most clean-shaven men in history - they waxed their faces with beeswax).

Cornelius is fascinated by Christianity and feels attracted to this religion that makes men serene and - it seems to him - self-confident. But after the meal, Peter is rebuked by a group of Christians who see him coming out of Cornelius’ house with stern words: “You entered the house of uncircumcised men and ate with them!” (Acts 11:3).

The explanation for this reference to circumcision lies in the fact that in the beginning, Christianity followed the dietary rules of the Jews, the central figures of that new religion being all of Jewish origin. In the context of the meal Peter ate with Cornelius, it could not be known how pure the foods they had eaten were. There were preparations from ancient Rome such as pork ventriglium (i.e. the stomach in which scraps of meat and entrails mixed with congealed blood are cooked). As in the Jewish religion, in early Christianity animal blood was forbidden in food.

The most reliable source of this food ban in early Christian times is given to us by Tertullian of Carthage (c. 155-230), in two of his texts: ‘Apologeticum’ and ‘De Præscritpione Hæreticorum’. Tertullian has several merits for Western culture. Among other things, we owe to him the expression ‘free will’: he first used the term ‘liberum arbitrium’ to translate the Greek αὐτεξούσιος (autexousios) of Epictetus.

He is also a fervent advocate of healthy and restrained eating, in fact he writes: “One does not lie down to eat until after a prayer to God. One eats according to one’s hunger, one drinks as modest people should, one satisfies oneself as one who does not forget that one must also worship God at night. One talks like one who knows that God listens”.

At the end of the second century and the beginning of the third, Tertullian is among the first Christian writers in Latin and certainly one of the very first theologians to write in this language. In his writings he uses a specifically technical language taken from the jargon of lawyers and constructs the sentences in a deliberately irregular way, with interrogations, exclamations, wisecracks, puns, anastrophes and metaphors, so as to make the discourse more incisive. His style is vehement, polemical and harsh, both when he speaks of abortion (which he defines as “early murder”) and of food prohibitions, referring specifically to blood, which was forbidden in the Christian diet.

At the end of the second century and the beginning of the third, Tertullian is among the first Christian writers in Latin and certainly one of the very first theologians to write in this language. In his writings he uses a specifically technical language taken from the jargon of lawyers and constructs the sentences in a deliberately irregular way, with interrogations, exclamations, wisecracks, puns, anastrophes and metaphors, so as to make the discourse more incisive. His style is vehement, polemical and harsh, both when he speaks of abortion (which he defines as “early murder”) and of food prohibitions, referring specifically to blood, which was forbidden in the Christian diet.

Moreover, in the 7th century, in 692 to be precise, the Council in Trullo, also known as the Quinisextum Council, held in Constantinople, expressly forbade the consumption of any food containing blood. Not only, but the punishments for those who contravened were severe: excommunication for the people and dismissal for the priests. It was only later, from the end of the 19th century, that foods containing blood as an ingredient began to be tolerated. These include a number of preparations, such as sweet black pudding in Lucania and Campania, black pudding from the British Isles, Schwarzsauersuppe (black sour soup) from northern Germany, Polish czernina (another soup) or Vietnamese tiết canh, made with blood and freshly slaughtered duck meat.

Blood, usually mixed with cubes of pork fat, is also used to make various sausages, such as German Blutwurst, Spanish morcilla, and boudeun from Valle d’Aosta. The blood also acts as a binding agent and can be used to make civet, a brown sauce, or to accompany game.

Consumption of blood is often seasonal and, due to the limited shelf life of the food, is usually associated with the period when animals (e.g. pigs) are slaughtered.

In some populations, the blood of animals can also be used without killing them. For example, the Masai take blood from the arteries in the neck of the cattle they raise and consume it warm or after mixing it with milk; the animal usually recovers relatively quickly.

The prohibition imposed on Noah in Genesis 9:3-6 was valid for all his descendants and did not include only animal blood, a principle highlighted in the 1st century when Christians were commanded at the meeting known as the Council of Jerusalem to ‘abstain from blood’ (Acts 15:28,29).

The prohibition imposed on Noah in Genesis 9:3-6 was valid for all his descendants and did not include only animal blood, a principle highlighted in the 1st century when Christians were commanded at the meeting known as the Council of Jerusalem to ‘abstain from blood’ (Acts 15:28,29).

In biblical Judaism, the taboo on blood, as a ‘sacred prohibition or ban’, dates back to the dawn of time. Genesis describes the first generations of men as vegetarians, eating mainly fruit (1: 29). In the transition from vegetarian to post-diluvian carnivorous diets, the first blood taboo was born. According to the narrative, God gave Noah permission to kill animals for food with a strict condition: “Only you shall not eat the flesh with its life, that is, its blood” (9:3).

How then did the use of animal blood in various recipes of various peoples come to be tolerated, as described above? Well, perhaps because Jesus himself allowed it. A Jew of the tribe of David, he hated Jewish formalisms. Therefore, speaking of food he said, “Do you not understand that whatever enters a man from without cannot defile him, because it does not enter his heart but his belly and goes down into the sewer?” (Mark 7:14,19).

Such a sentence might make one smile, yet Jesus uttered it. We can thus conclude that Christians, with the exception of a few minor groups (Jehovah’s Witnesses, Adventists), do not know or practice forms of food deprivation/exclusion for religious purposes.

Returning to our subject today, foods cooked with blood do not have many takers, except in areas where these dishes are traditional. Beyond religious precepts, this habit remains a matter of taste and as such, very personal.