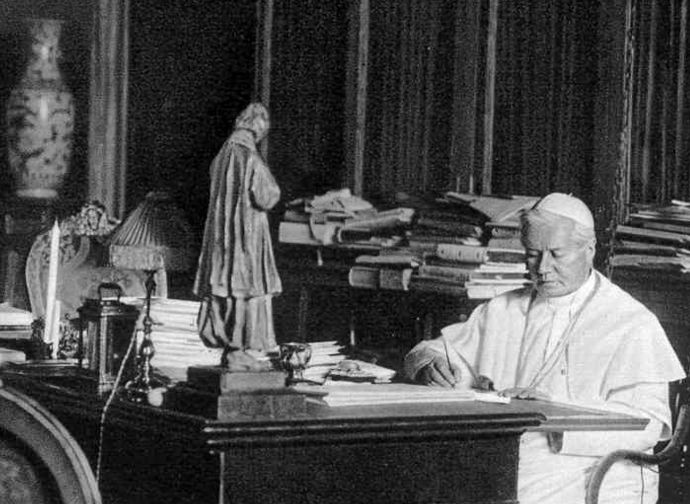

Saint Pius X

He was able to analyse lucidly and condemn the errors of Modernism. His great devotion to the Virgin and love for the Eucharist nourished his holiness. He supported the Cecilian Movement, which wanted to give back the deserved space in the liturgy to Gregorian chant

“Restoring everything in Christ” was the inspiring principle of the 11 years of the pontificate of Saint Pius X (1835-1914), the Pope of humble origins who was able to analyse lucidly and condemn the errors of Modernism. He recognized its evil roots and prophesied that it would lead to an atheistic society. The Holy Father addressed the issue organically in his most famous encyclical, Pascendi Dominici Gregis (8 September 1907), in which he defined Modernism as “the synthesis of all heresies”. Pius X was well aware that this pseudo-Christian current, which arose towards the end of the 19th century with the pretension of adapting the eternal message of Christ to social changes, attacked the very foundations of the faith, giving the nod to Freemasonry.

In the past as in the present, the Modernists rejected the dogmas and teachings of the ancient Fathers, rejected the authority of the Pope, theorized religious indifferentism and the subjection of the Church to the State, extolled modern philosophy by despising Scholasticism; disconnected faith and reason; denied the truth of the Holy Scriptures, the institution of the Sacraments by Christ, the miracles and the workings of God in history. Thus Saint Pius X wrote: “The first step in this direction was taken by Protestantism; the second is made by Modernism; the next will plunge headlong into atheism”. Knowing that he had to act for the salvation of souls, during his pontificate the major exponents of Modernism were excommunicated or suspended a divinis and the teachers - religious and lay - who favoured that system of heresies were removed from seminaries and Catholic universities. He gave priority over the world's consent to the search for and fulfilment of God's will, always with the humility that had led him to call himself “a poor country parish priest”.

Giuseppe Sarto, the second of ten children, was born in Riese (in the province of Treviso) to a family of modest conditions. His father Giovanni Battista was a farmer and his mother, Margherita (née Sanson), a seamstress rich in faith, who at the death of her husband did not consent to her second son leaving the seminary to help the family. Giuseppe was ordained a priest at the age of 23. After being chaplain, archpriest, canon, spiritual director in a seminary, he was appointed bishop of Mantua at the age of 49, and distinguished himself for his focus on religious formation. “Christian doctrine! Christian doctrine!”, he would cry during his pastoral visits to the various parishes, as he was aware that “attending Mass and ignoring the truths of the faith are things that cancel each other out, because it is not possible to accept truths that are not known”.

In 1889 he participated in the first National Catechetical Congress and voted in favour of a new “popular historical-dogmatic-moral catechism written in short questions and very short answers”. He then decided to compose a dialogical text himself. This developed into the famous Major Catechism (later called the Catechism of St Pius X), whose first edition - made up of 993 questions and answers - was published in the third year of his pontificate (1905) and was followed by two shorter versions.

His election to the papal throne, preceded by a decade as Patriarch of Venice, took place on 4 August 1903. Two months later he expounded his programme in the first of his 16 encyclicals (E Supremi): “The interests of God shall be Our interest, and for these We are resolved to spend all Our strength and Our very life. Hence, should anyone ask Us for a symbol as the expression of Our will, We will give this and no other: To renew all things in Christ.”

Along the same lines the new pontiff supported the Cecilian Movement, which wanted to give back the deserved space in the liturgy to Gregorian chant and classical polyphony, in the awareness that “sacred music, as an integral part of the solemn liturgy, participates in the general purpose, which is the glory of God and the sanctification and edification of the faithful” (Inter Sollicitudines).

His great devotion to the Virgin and love for the Eucharist nourished his holiness. He recommended attending daily Mass and brought the age of Confession and First Communion back “to the age of reason” (7 years). Given the growing attacks on the innocence of children, Pius X (like other saints) supported the need to have them approach the Body of Our Lord as soon as possible.

One fact among many reminds us how strong his faith was and how Christ was the centre of his life. A few days after receiving from St Hannibal Mary di Francia (founder of the Rogationists) the manuscript with the revelations of Jesus to the most humble Luisa Piccarreta, Saint Pius X said to him: “Have Piccarreta’s Hours of the Passion printed immediately. Read it on your knees, for it is Our Lord who speaks!”.