Rupnik's works discourages worship, “it’s not sacred art”

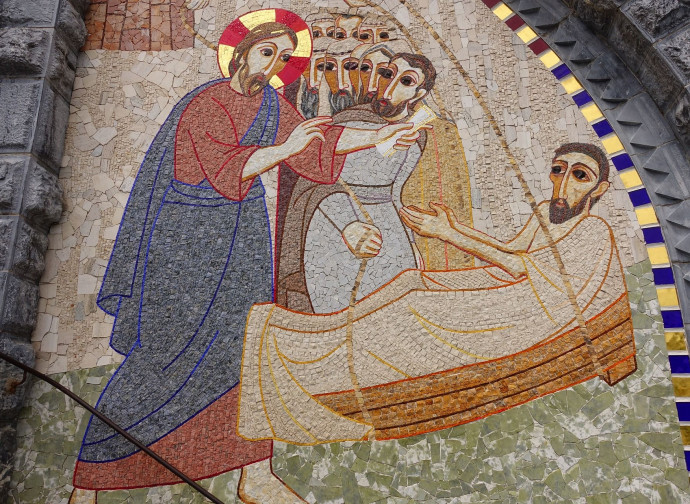

On the debate started in Lourdes about Rupnik's works, which questions all the faithful, the Daily Compass interviewed Fr Nicola Bux: “The situation of sacred art has contributed to secularisation and the loss of faith. And Rupnik positioned himself in this void. The commissioning bishops should ask themselves whether the faithful, looking at Rupnik's art, are inspired to pray or rather to dance around the golden calf, which is ourselves”.

In Lourdes, there is a debate on what to do with Rupnik's works. Besides the moral problem, the question must also be asked whether Rupnik's mosaics are really liturgical art. The Daily Compass interviewed Fr Nicola Bux.

Fr Nicola, let us begin by understanding what are the criteria of authentic liturgical art.

Pope Saint John Paul II, on the occasion of the 12th centenary of the Council of Nicaea II, said that the dictates of that Council had not yet been fully received by the West. Strong words. The Council of 787 dictated criteria for the veneration of images and their production. The central criterion was that the Apostolic Tradition was to be respected and increased organically, so that the decisive fact of Christianity, the Incarnation of the Word, remained the prototype. The icons had to stand in relation to the Prototype.

And was this observed?

In the East, yes, perhaps in a way that may appear somewhat fixist to us; in the West it was developed gradually. One thinks of Cimabue, Giotto, and Angelico, who did not violate the rules of Byzantine painting, but developed them, always with an eye to safeguarding the Prototype, the One who with the Incarnation allowed Himself to be circumscribed in the Virgin's womb. Because when an image is proposed, it is a question of understanding whether the faithful who contemplate it can worship it, cultivate a relationship of veneration, supplication, prayer, which is the meaning of icon production. In my opinion, these canons were gradually abandoned and we arrived, in the West, at a vacuum that had to be filled.

Does this also imply a void of guidance from the Church?

I think the last directives were those of Cardinal Gabriele Paleotti and St Charles Borromeo. Later, yes, speeches were made, but that was it. In Chap. 7 of Sacrosanctum Concilium there are indications on sacred art, but with passages that left gaps open to styles and manners that could not be canonised; in fact, anything and everything was produced, to the point of introducing the abstract, which is the opposite of the incarnate, into the churches. This has left artists free, and even the artist completely unfamiliar with faith and prayer has produced art for the liturgy. The situation of sacred art has contributed to the secularisation and loss of faith.

Does this have anything to do with Rupnik's artistic production?Rupnik followed this wave and stepped into that void I mentioned. The clerics had lost their taste, they no longer had any criteria; they therefore received this vaguely Orientalising art uncritically. However, they never asked themselves whether the faithful facing Rupnik's art were led to prayer or rather to dancing around the golden calf, which is ourselves. I remember that an art critic, Achille Bonito Oliva, used to say that art serves to desecrate. Art is no longer mimesis, which makes the Prototype approachable, but a creation from nothing. I think this can help us understand Rupnik's works.

The Auxiliary Bishop of Warsaw, Michał Janocha, stated (see here) that Rupnik's art is disturbing and repels the gaze of the person in prayer.

That the bishop made this statement is very interesting. I happened to receive a request for an opinion from a parish priest who had mosaicked the apse of his church with a work by Rupnik. I posed the question: do you wonder whether, looking at these images, the faithful pray, enter into a relationship with those depicted? The parish priest was bewildered and this confirmed to me that one of the most important canons of Christian art has been lost: there is no longer a relationship with the Prototype. In Renzo Piano's new church, where they had placed Arnaldo Pomodoro's abstract cross, they removed it and replaced it with a serial crucifix. In Lourdes, in the underground church of St Pius X, years ago, there was a crucifix that was a silhouette of scrap metal. I pointed it out to one of the chaplains and he replied that no one looked at it anyway. So then why was it put there?

You had as a teacher Fr Tomas Spidlik, considered Rupnik's mentor.

A gentle man of faith and very cultured. I remember that he was against Oriental icons in Western churches, because he pointed out that Oriental icons can only be explained within the Oriental liturgy. This makes one thing clear: that the East conceives of sacred art in unity with the liturgy. Whereas here we build a church and then, if there is money and time, we try to place an image of Our Lady or of one or other saint, like postage stamps. For the East, the iconographic programme is one with the design of the church. It is not a matter of placing an image to fill an empty space, but that the liturgy has its own visual element, just as it has its auditory and olfactory elements, consistent with the liturgy itself. That Spidlik had this conviction begs the question of how it was possible that Rupnik convinced him of a transposition to the West of this art which, according to him, should combine the Oriental with the Latin. Oriental in a manner of speaking, because Rupnik's figures take on movements unknown to Oriental art.

Liturgical art, which was already in crisis before the Council, found itself in a liturgical do-it-yourself. And has thus become, in turn, a do-it-yourself art.

I agree. If artists have been able to manipulate sacred art, it is because priests have been able to manipulate the liturgy to their liking. Even if they then took it out on the faithful, accusing them of devotionalism. But no one dares to say that sacred art has become a "sampler of memorised human rules" (Is 29:13). So has worship. And God turns his back, because they have fallen into idolatry.

According to some, however, Rupnik's art is a lifeboat against decay, re-proposing a properly sacred art.

In this debacle, Rupnik may have curbed a total drift. But what has he produced? He may have curbed it from an aesthetic point of view, perhaps, but from the point of view of worship, as we have said, what has he produced? Why is it that so many of the faithful in San Giovanni Rotondo do not want to enter the new church? The faith-art relationship is decisive. It also applies to music.

Have we fully understood what the proprium of the liturgy is, so that everything is suited to it? We have gone from a perception of Christ incarnate and present to a vision that is gnostic and evanescent, abstract and therefore deistic. To the point that today the priest when he prays is no longer able to fix his gaze on an image: he prays in a vacuum, accentuated by his orientation towards the people. How much does the image created by Rupnik help this fixing of the gaze, to contemplate?

The debate has opened on what to do with Rupnik's works. It is usually objected that other artists also did not have a virtuous moral life. But here the issue is different: Rupnik lived a morally reprehensible life supported by a false mysticism and a false Trinitarian theology. How can this not enter into artistic production?Exactly. One can also assume that every man can convey a glimmer of truth. But here the question concerns the mixture between a deformed mystical conception and a mystery representation that is proposed. The moment the believer learns about certain things, the question cannot help but arise as to whether that art is involved with that deformed conception. Today, in particular, one can hardly remain unaware of what happened. If bishops and the faithful have asked themselves this question, this is already a fact and it must be addressed seriously.