Pius V and Scappi served up illustrated gastronomy book

St Pius V was a remarkable pontiff who did a great deal to defend the faith. Although he ate frugally, he had the finest cook of the Renaissance (inherited from his predecessor): Bartolomeo Scappi. Thanks to Pope Ghislieri, he published ‘Opera dell’arte del cucinare’, the first illustrated book on gastronomy. And in May, a film will be released, ‘Il Cuoco del Papa’ [The Pope’s Cook], based on this historic publication.

Pius V (1504-1572) was a remarkable pontiff. What one has to admire most in him is his consistency, understood as fidelity to the role of priest, who had to defend the Christian faith at all costs. And he always did so, at every moment of his life.

He was from Bosco Marengo, in Piedmont (province of Alessandria), born Antonio Ghislieri. Although of humble economic status, the Ghislieri were the eldest branch of a powerful Bolognese family, who arrived in Piedmont after being exiled from Bologna due to disagreements with the emerging Bentivoglio seigniory over ascendency in the city. His vocation was precocious. At the age of 14 he was already in the Dominican convent in Voghera, where he took the religious name of Michael. He was immediately noticed by his superiors for his uncommon intelligence, but above all for the austerity of his life, which he maintained until his death. This behavioural trait was the basis for all his perspectives and decisions. Therefore, after his solemn vows in 1519 and his humanistic and theological education, he was sent to the University of Bologna to perfect his theological training. There he received a solid Thomist education. Finally, in 1528 he was ordained a priest by Cardinal Innocenzo Cybo.

He was from Bosco Marengo, in Piedmont (province of Alessandria), born Antonio Ghislieri. Although of humble economic status, the Ghislieri were the eldest branch of a powerful Bolognese family, who arrived in Piedmont after being exiled from Bologna due to disagreements with the emerging Bentivoglio seigniory over ascendency in the city. His vocation was precocious. At the age of 14 he was already in the Dominican convent in Voghera, where he took the religious name of Michael. He was immediately noticed by his superiors for his uncommon intelligence, but above all for the austerity of his life, which he maintained until his death. This behavioural trait was the basis for all his perspectives and decisions. Therefore, after his solemn vows in 1519 and his humanistic and theological education, he was sent to the University of Bologna to perfect his theological training. There he received a solid Thomist education. Finally, in 1528 he was ordained a priest by Cardinal Innocenzo Cybo.

As a priest, he was first a professor at the universities of Pavia and Bologna, while at the same time also holding posts in the Dominican Order, of which he was elected provincial superior for Lombardy in 1542, where he remained for a few months before joining the Holy Inquisition as commissioner and inquisitorial vicar for the Diocese of Pavia.

His patron was Cardinal Gian Pietro Carafa, who, after becoming Pope Paul IV, commissioned him to draw up the Index librorum prohibitorum and then appointed him ‘Grand Inquisitor of the Holy Roman and Universal Inquisition’ with unlimited and ad vitam powers. The next pontiff, Pius IV (who confirmed him in the posts), did not have his same intransigence, so differences arose that led to Ghislieri’s transfer to Mondovì, of which he was appointed bishop. Soon, however, on 7 January 1566, after the death of Pius IV, Ghislieri became the 225th Pope.

During his pontificate he did a great deal for the Christian faith and the reorganisation of the Church. He fought with all his might against nepotism, heresy, the immorality of priests, the Lutherans and the Ottomans. He regulated the rule of cloistered female monasteries, issued several bulls, one in particular in defence of animals: De salute gregis, which banned bullfighting, very much in vogue in Rome. With the bull Consueverunt Romani Pontifices he promoted the devotion of the Rosary. He also codified the Holy Mass, confirming the liturgy adopted by the Council of Trent. In 1568, with the bull Quod a Nobis, he promulgated the new Roman Breviary (also known as the Breviary of St Pius V), imposing it on all Catholic secular and regular clergy. He considered the Waldensians and Queen Elizabeth I Tudor, whom he excommunicated in 1570, to be heretics.

He had a different attitude towards the Jews: he hoped to convert them and decided not to expel them from Italian territory, as had happened in Spain (the largest Catholic power at the time). Pius V used the Venetian model: in the lagoon city the Jews who had arrived after the Spanish expulsions were confined to an island. The Roman Jews were confined in the ghetto, located in a specific area of the Sant’Angelo district, from which the Christians were expelled.

He had a different attitude towards the Jews: he hoped to convert them and decided not to expel them from Italian territory, as had happened in Spain (the largest Catholic power at the time). Pius V used the Venetian model: in the lagoon city the Jews who had arrived after the Spanish expulsions were confined to an island. The Roman Jews were confined in the ghetto, located in a specific area of the Sant’Angelo district, from which the Christians were expelled.

Pius V is also credited with having created the first papal secret service, called the ‘Holy Alliance’. It was in this way that he learned in time of the Ottomans’ intention to invade the Papal States and Christendom and promoted the Holy League at the Battle of Lepanto (7 October 1571). With this act of extraordinary courage the pontiff succeeded in uniting Catholic Europe for the time of one battle (except France, which refused to join). In the Vatican Museums there is a splendid painting by Veronese, who participated in the Battle of Lepanto.

The biography of Pius V helps us to understand his complex and sometimes contradictory personality, especially when it came to ‘earthly’ matters. We refer to his relationship with food: he was what today would be called ‘anorexic’ (his basic meal consisted of water and stale bread), but he had the finest cook of the Renaissance, Bartolomeo Scappi (1500-1577), whose genius was put to good use by the Pope to welcome diplomats and pilgrims. Scappi was from Bologna, the city where he spent the first part of his career as a cook in the service of Cardinal Lorenzo Campeggio, for whom he created a sumptuous banquet in honour of Charles V in 1536.

Scappi’s influence was decisive in the evolution of European cuisine. Inspired by his predecessors (Maestro Martino and Platina), Scappi was an innovator: he introduced into his recipes new and hitherto unknown ingredients from the Americas, but also products neglected by medieval gastronomy, such as offal, butter, whipped cream, and poor herbs (the ‘broths’ of nettles, mallow, wild asparagus, and various roots are extraordinary). He created new ravioli recipes and also the first recipe for stuffed turkey (unknown in Europe before the discovery of America). He became the cook of Pius IV and then Pius V kept him in his service.

Scappi’s influence was decisive in the evolution of European cuisine. Inspired by his predecessors (Maestro Martino and Platina), Scappi was an innovator: he introduced into his recipes new and hitherto unknown ingredients from the Americas, but also products neglected by medieval gastronomy, such as offal, butter, whipped cream, and poor herbs (the ‘broths’ of nettles, mallow, wild asparagus, and various roots are extraordinary). He created new ravioli recipes and also the first recipe for stuffed turkey (unknown in Europe before the discovery of America). He became the cook of Pius IV and then Pius V kept him in his service.

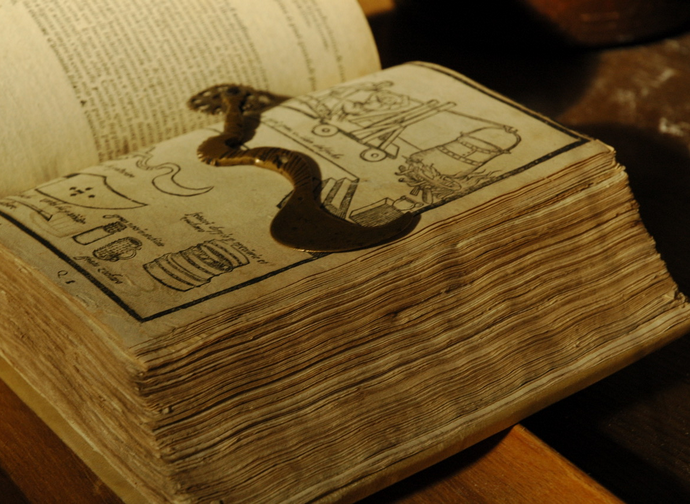

It is natural to ask: what did a hieratic Pope who ate frugally, to say the least, and an extravagant cook who amazed with his spectacular culinary creations, have in common? Perhaps nothing, yet they will forever be united by a book. A recipe book. Written by Scappi and published thanks to funding from Pius V. The book is Opera dell’arte del cucinare, which is the first illustrated gastronomy book in history. The author of the illustrations is Bartolomeo Scappi himself. In 27 marvellous plates we can admire the detailed contents of a Renaissance kitchen: the crockery, the ways of storing food, the cuts, the cooking, the methods of preservation (smoking, salting, drying in the wind). We even see a travelling saddle for the cook, a collection of pasta wheels, a multiple spit created by Michelangelo (which Scappi often used) and a large variety of water buckets: remember that in past centuries there was no running water, so in the organisation of a kitchen part of the staff was assigned to transporting water.

It is natural to ask: what did a hieratic Pope who ate frugally, to say the least, and an extravagant cook who amazed with his spectacular culinary creations, have in common? Perhaps nothing, yet they will forever be united by a book. A recipe book. Written by Scappi and published thanks to funding from Pius V. The book is Opera dell’arte del cucinare, which is the first illustrated gastronomy book in history. The author of the illustrations is Bartolomeo Scappi himself. In 27 marvellous plates we can admire the detailed contents of a Renaissance kitchen: the crockery, the ways of storing food, the cuts, the cooking, the methods of preservation (smoking, salting, drying in the wind). We even see a travelling saddle for the cook, a collection of pasta wheels, a multiple spit created by Michelangelo (which Scappi often used) and a large variety of water buckets: remember that in past centuries there was no running water, so in the organisation of a kitchen part of the staff was assigned to transporting water.

The Pope, who took the time to look at the drawings as Scappi produced them, even decided to put his notary at the cook’s disposal for the drafting of the manuscript, explaining that the latter had good ink and quality parchment, so the text and drawings would last forever. Then, again thanks to Pius V, the printer Michele Tramezzino of Venice was contacted and the book was printed. It contains hundreds of recipes, but is also a kind of ‘diary’ of the banquets prepared by Scappi, where the cook notes down the menus and the names of the participants.

This writer’s production company, Condor Pictures, made a film about the publication of this book and the special bond between Scappi and Pius V, two men who were so different in their approach to gastronomy, but thanks to whom a masterpiece of gastronomic literature, the Opera dell’arte del cucinare, has come down to us. We reproduced all the utensils depicted in the book, even Michelangelo’s spit. The film, called Il Cuoco del Papa [The Pope’s Cook], will be released on DVD in May, together with another film called Il Cuoco del Vaticano [The Vatican Cook], which tells the story of Platina’s book, which we have already mentioned (see here).

This writer’s production company, Condor Pictures, made a film about the publication of this book and the special bond between Scappi and Pius V, two men who were so different in their approach to gastronomy, but thanks to whom a masterpiece of gastronomic literature, the Opera dell’arte del cucinare, has come down to us. We reproduced all the utensils depicted in the book, even Michelangelo’s spit. The film, called Il Cuoco del Papa [The Pope’s Cook], will be released on DVD in May, together with another film called Il Cuoco del Vaticano [The Vatican Cook], which tells the story of Platina’s book, which we have already mentioned (see here).

We are paying homage today to two chefs (Platina and Scappi) who have made not only gastronomy celebrated, but also Italy. Thanks to them, Italian gastronomy was considered the leader in Europe until the mid-seventeenth century, when culinary supremacy would pass, with La Varenne, into the hands of France and would remain there until the twentieth century, when Italy regained the upper hand.