Missionary Peter Chanel, protomartyr of Oceania

He had been passionate about the missions since he was an adolescent. He became a priest, but for years he was unable to fulfil his desire to leave. He succeeded after joining the Marists, going as a missionary to the island of Futuna. He cared for the sick, baptised dying children, and converted many to Catholicism. He was killed for his faith, becoming the protomartyr of Oceania.

- THE RECIPE: FISH SALAD FROM FUTUNA

The captain of the French ship stationed in Tahiti, which has been sailing for the last two days towards the islands of Wallis and Futuna, boards the boat moored alongside. On the boat there are six of his crew and the ship's priest, who is also part of the crew. The men are silent, there is always some apprehension when approaching the islands, especially on a small boat like this. The captain savours the beauty of the place as it gets closer and closer: turquoise sea, white sand, green palm trees. The colours create an indescribable harmony. But he remembers that he is not there to admire nature, but for an onerous and unpleasant task. Those damned savages have bestially murdered a missionary and he and his companions have the task of giving the remains a decent burial. He looks at the solemn face of the ship's straight-backed priest.

At last they are close to the beach and two sailors jump into the water and tow the boat by hand. On the beach there is a small group of natives. They have a strip of cloth around their loins and wooden crosses hanging around their necks. Christians, no doubt. The commander knows the work of the Marists, missionary fathers who came from France to Christianise the natives. He knows that they did great things, often at the sacrifice of their own lives, as in this case. What a waste, he thinks.

At last they are close to the beach and two sailors jump into the water and tow the boat by hand. On the beach there is a small group of natives. They have a strip of cloth around their loins and wooden crosses hanging around their necks. Christians, no doubt. The commander knows the work of the Marists, missionary fathers who came from France to Christianise the natives. He knows that they did great things, often at the sacrifice of their own lives, as in this case. What a waste, he thinks.

They disembark and the priest talks to the natives: he knows their language. They all head for the small palm forest and walk for a quarter of an hour. They go deeper and deeper into the vegetation, the commander is hot and sweat drips from the blond hair on his forehead. Finally they arrive and two of the natives start digging. They work quickly and shortly afterwards the edges of a rough fabric appear. The commander expects to smell the usual stench of corpses, but no odour emanates from the makeshift grave. Finally, the two carefully and reverentially extract the poor remains. They place them on a stretcher made of two wooden poles, intertwined branches, and coconut leaves. The ship’s priest steps forward and makes the sign of the cross over the body, then sprinkles it with a small bottle of holy water that he takes out of his pocket. He says a prayer, then makes a sign to the natives. The small procession makes its way back to the moored boat. The captain wipes his forehead and says a silent prayer for the body lying on the makeshift stretcher.

The body belonged to Father Pierre Chanel (1803-1841), anglicised as Peter, a Marist missionary cruelly murdered by the natives who opposed the Christianisation of the island. Born in 1803 in France, in Cuet, in the Ain region, Pierre Chanel came from a modest family: he was the fifth of eight children. As a child he loved to play at celebrating Mass. He had the good fortune of meeting a priest who understood his deep faith and unusual intelligence and who helped him to discern his vocation. Father Trompier, curate of a small village not far from Cuet, took him under his wing and gave him a good religious education, as well as making him a regular altar server.

After his First Communion, on March 23, 1817, he became engrossed in reading the letters of the missionaries sent by Bishop Louis-Guillaume-Valentin Dubourg (1766-1833), who had returned from America. He would later confide: "This is the year in which the plan to go to the distant missions took shape in my mind". At his Confirmation, he took Saint Louis Gonzaga as his second patron. After his studies at the minor seminary, he attended the major seminary. On 15th July 1827 he was ordained a priest. He was vicar in Ambérieu-en-Bugey and parish priest in Crozet, where he left lasting memories of his kindness. The desire to travel to evangelise distant lands remained strong in him. But his bishop, Monsignor Alexandre-Raymond Devie, refused to let him go and Peter obeyed.

At one point, Father Chanel asked his bishop for permission to join the Society of Mary, founded in 1822 by Jean-Claude Colin (1790-1875). He joined in 1831. He hoped the Holy Father would soon authorise their establishment as an independent missionary society and open the way to the oceans... In the meantime, however, he became a lecturer at the minor seminary in Belley, where there were students particularly fond of him. Following Pope Gregory XVI's decision to send missionaries to Oceania, a mission particularly entrusted to the Society of Mary, Peter Chanel volunteered. He embarked on the Delphine on 24 December 1836, and left Le Havre, in Normandy, for Chile and then Oceania.

At one point, Father Chanel asked his bishop for permission to join the Society of Mary, founded in 1822 by Jean-Claude Colin (1790-1875). He joined in 1831. He hoped the Holy Father would soon authorise their establishment as an independent missionary society and open the way to the oceans... In the meantime, however, he became a lecturer at the minor seminary in Belley, where there were students particularly fond of him. Following Pope Gregory XVI's decision to send missionaries to Oceania, a mission particularly entrusted to the Society of Mary, Peter Chanel volunteered. He embarked on the Delphine on 24 December 1836, and left Le Havre, in Normandy, for Chile and then Oceania.

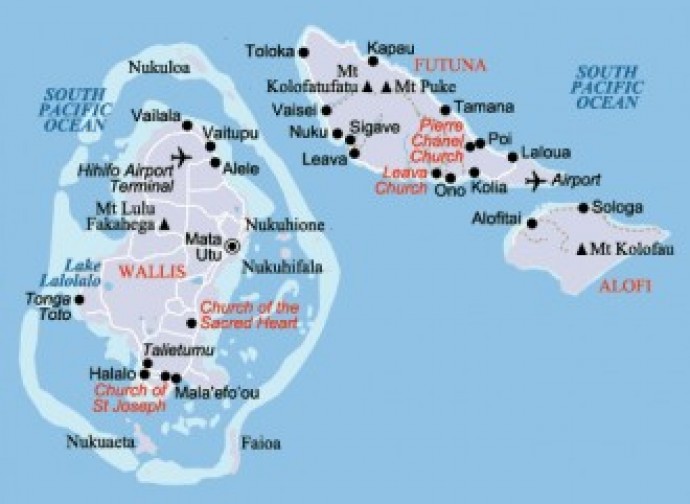

After nearly 11 months of travel, on 7 November 1837, Father Chanel settled with his confrere Marie-Nizier in Futuna, West Polynesia, while another group of Marists landed in Wallis. Discovered in 1616 by the Dutch, the island of Futuna was nicknamed "the lost child of the Pacific" by Bougainville in 1768 because it had never been evangelised. Tribal wars and the practice of cannibalism had reduced the population to a few thousand when Chanel landed on its shores.

Chanel worked hard with faith amidst great difficulties, caring for the sick and earning the nickname “man with a kind heart”. Niuliki, the ruler at the time, initially took a friendly attitude towards the missionary, even calling him 'taboo', i.e. sacred and inviolable. For two years, hosted by King Niuliki, Father Chanel learned the local language and baptised dying children. Following the example of St Paul, he discovered the island, its inhabitants, its customs, and tried to become a Futunan with them. This process of personal enculturation allowed him to begin his work of evangelisation. With patience and charity he cared for the sick and wounded. He acted to end the wars between tribes: in 18 months, he enabled the two kingdoms of the island to make peace.

Chanel worked hard with faith amidst great difficulties, caring for the sick and earning the nickname “man with a kind heart”. Niuliki, the ruler at the time, initially took a friendly attitude towards the missionary, even calling him 'taboo', i.e. sacred and inviolable. For two years, hosted by King Niuliki, Father Chanel learned the local language and baptised dying children. Following the example of St Paul, he discovered the island, its inhabitants, its customs, and tried to become a Futunan with them. This process of personal enculturation allowed him to begin his work of evangelisation. With patience and charity he cared for the sick and wounded. He acted to end the wars between tribes: in 18 months, he enabled the two kingdoms of the island to make peace.

But after several conversions to the Catholic faith (in Futuna less than in Wallis, which had become entirely Christian), King Niuliki became angry when he saw that his subjects were being led away from their idols towards the religion of the white man. He therefore issued an edict against him to discourage conversions. At the same time his son Meitala converted to Catholicism. The king decided to stop housing and feeding the missionaries and began a series of persecutions to drive them out.

Despite everything, the missionaries remained faithful to their ministry, and because of their touching witness there were still a few conversions (including that of the king's son). Perhaps this was the straw that broke the camel's back. The king decided to put an end to the missions in his land: "Religion must die with those who brought it!".

At dawn on 28 April 1841, conspirators hostile to the Catholic faith - led by Musumusu, the king's prime minister - gathered and, after wounding several neophytes caught in their sleep, attacked Chanel's hut. One of them chopped up his arm and wounded him in the left temple with a club. Once on the ground, the priest was attacked with a bayonet, while a third assailant struck him heavily with a bludgeon. While the missionary uttered words of serene resignation ('Malie fuai', i.e. 'good for me'), Musumusu himself, angry at his resistance, split the martyr's skull with an axe. The remains of the missionary, hastily buried, were later claimed by Captain Lavaux, the French commander of the Tahitian naval station, on the day our story begins. Peter's remains were then brought back to France by government transport in 1842. The Congregation of Rites gave him the title of "Protomartyr of Oceania". Beatified in November 1889 by Leo XIII, he was canonised on 12 June 1954 by Pius XII.