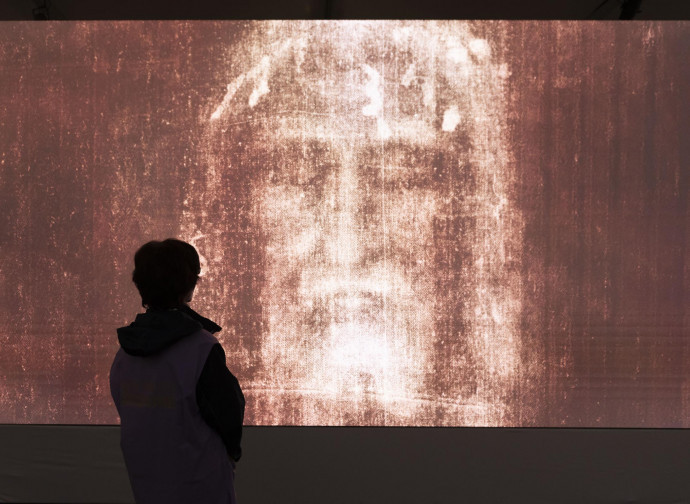

An insignificant study attempts to discredit Holy Shroud

Cicero pro domo sua: Cicero Moraes revisits last summer's catchphrase, which claims that the image of the Holy Shroud is the result of a bas-relief. This is an unfounded thesis, much like his clumsy reply which ignores and distorts the studies of others in order to deny the uncomfortable truth.

We have not forgotten last summer's catchphrase: the news that the image on the Holy Shroud was produced by a bas-relief. Notably, this research has little, if not zero, significance. At the time, on 4 August, we discussed it because, astonishingly, this study was published in the prestigious University of Oxford journal Archaeometry, which in 2019 hosted our definitive refutation of the medieval dating of the Shroud.

The request to publish a commentary was sent to Archaeometry, written by myself, Tristan Casabianca and Alessandro Piana, three Shroud scholars. In the paper, we highlighted some unacceptable points in Cicero Moraes' work, underscoring the most serious one: he deliberately fails to consider all aspects of the Shroud. He disregards the studies of eminent scientists published in peer-reviewed journals. He does not consider studies on aspects that do not concern the formation of the image, such as microtraces and blood, nor research into the origin of the image. On this subject, he makes statements against the authenticity of the Shroud and claims to have the final word. This arrogance is scientifically unacceptable. It is ridiculous to claim to study an object as complex as the Shroud without acknowledging the results of previous research.

Moraes decides a priori that there was no corpse on the Shroud. He therefore embarks on this erroneous path and follows it with confidence, satisfied with his decision. All our criticisms of his work have now been published by Archaeometry and were already known because they were in the August article. What is new is Moraes' response to our criticisms.

In the abstract, he states the following: 'The response to the comments by Casabianca et al. (2025) aims to clarify interpretative misunderstandings and reaffirm the methodological consistency of the study, "Image Formation on the Holy Shroud — A Digital 3D Approach".' The criticisms presented ignore the stated scope of the research, which is strictly methodological in nature and focuses on evaluating morphological deformation in the projection of the body onto the fabric. The exclusive use of the frontal region, the choice of visual sources and the historical contextualisation based on tomb effigies are consistent with the proposed objective and are supported by previous studies. The response emphasises the transparency of the data, the replicability of the experiment and the legitimacy of the scientific approach adopted, refuting accusations of conceptual or historical flaws.'

Nevertheless, Moraes persists in ignoring the studies of others, but with one significant distinction: he disregards those that support the Shroud's authenticity and considers those that deny it. He refers to this when he writes that his choices 'are confirmed by previous studies'.

However, he goes further still, attempting to confuse the reader with partial quotations that distort their meaning.

Here is an example. In his reply, he discusses the 'commonly held assertion that the studies of the Shroud of Turin Research Project (STURP) indicated that the image did not result from pigmentation. However, according to Heller and Adler (1981), who were part of the group, 'It should be noted that although all other organic tests are negative, this does not exclude the possibility that some of these substances may have been present on the fabric at one time and been eliminated through oxidation, degradation, etc.'".

In this way, Moraes leads the reader to believe that, in their article, Heller and Adler admit that the image may have been formed by pigments that were lost over time. Therefore, the image would be fabricated art.

However, let us see how Heller and Adler's text continues: 'For example, the possible presence of fats or oils was verified by applying Hanus and Wij's standard iodine reagents (IBr, ICl). It was found that diluted solutions of this reagent were not released from the yellow fibrils, demonstrating that unsaturated fatty acids are not currently present on the fibrils. This does not exclude their possible past presence and subsequent loss through slow peroxidation. The same would apply to traces of Saponaria.'

Heller and Adler were looking for fats, oils, and Saponaria because they were testing the hypothesis that the image was caused by body sweat and perfumes in an oil solution with which the corpse, or the Shroud itself, may have been treated. Not an artist's pigment.

However, Moraes is so brazen that he even attempts to misquote the authors (Casabianca, Marinelli, Pernagallo and Torrisi) of the radiocarbon refutation published in Archaeometry in 2019. He writes, 'In relation to the carbon-14 study that the authors criticise and refer to, a passage they wrote (Casabianca et al., 2019) makes it very clear that the dating carried out in the 1980s should not be discarded: "Our statistical results do not imply that the medieval hypothesis on the age of the analysed sample should be excluded".'

Moraes wants the reader to believe that the authors ultimately admit that the Shroud is medieval.

However, let us consider the context and meaning of our statement here too. We are not talking about the entire Shroud, but the analysed sample. This is a sample of only three centimetres which is medieval because it has been mended and contaminated, with a difference of about 150 years between the two sides. We also write: 'This variability in nature's radiocarbon dating, within a few centimetres, if extrapolated linearly to the opposite side of the shroud, would lead to a date in the future.' We conclude: 'The measurements made by the three laboratories on the Turin Shroud sample are imprecise, which seriously compromises the 95% reliability of the 1260–1390 AD date range. Statistical analyses, corroborated by the foreign material detected by the laboratories, demonstrate the necessity of new radiocarbon dating to determine a reliable new interval. This new test requires a robust protocol within an interdisciplinary research project. Without this reanalysis, it is not possible to claim that the 1988 radiocarbon dating provides “definitive proof” that the age range is accurate and representative of the entire fabric.'

Moraes' clumsy and dishonest attempt at self-justification makes his claim that the Shroud is fake even more insubstantial. He is not the first and will not be the last. The Shroud bothers those who want to get rid of its uncomfortable presence, which questions and upsets those who do not want to admit its authenticity, lest they encounter Christ in their lives.