The adolescent Jesus in the work of a converted artist

John Rogers Herbert, raised as an Anglican, converted to Catholicism at the age of 30. From then on his art became more profound, the result of his desire to transmit faith through his work. His work influenced the Pre-Raphaelite movement.

There is an important English artist, John Rogers Herbert, whose work inspired the Pre-Raphaelites we talked about last week. He was born on 23 January 1810 in Maldon, Essex, and died in Kilburn on 17 March 1890. The county of Essex, situated in southern England, north-east of London, has an important record: within its boundaries lies the oldest city in Britain, Colchester, which was called Camulodunum at the time of the Roman conquest.

Herbert captures our attention for his painting of the teenage Jesus entitled Our Saviour Subject to His Parents in Nazareth of 1847: it is one of the few existing paintings to depict Christ in his teens and youth. But Herbert is also important to us for another thing: although raised as an Anglican, he converted to Catholicism at the age of 30. His conversion was thanks to his childhood friend, Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin (1812-1852), a Catholic, a brilliant architect and co-author of the reconstruction of the Palace of Westminster, which had been destroyed by a terrible fire in 1834.

It is important to underline Herbert's conversion, because thanks to this choice his art became more profound and more intimate: before this great step, the artist painted exclusively for a living and to earn money (portraits and commissioned works). By embracing Catholicism, John Rogers Herbert felt the need to give his paintings a more spiritual dimension. From that moment onwards, the artist felt invested with a single mission: to transmit faith through his work. He often states that he "works for the glory of God" and that he "feels like a handmaid in the service of the Lord". He is very proud of his religion, to which he devotes time and energy and speaks about it with devotion and love. Many of his works are inspired by the Gospels and characters from the Bible, and there are numerous representations of the Holy Land in his paintings.

In the meantime, he also began to rise in the academic world: first elected a member of the Royal Academy in 1841, he then became a full Royal Academician in 1846. His work influenced the newly founded Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (see here), who asked him to sponsor their publication The Germ.

Herbert's paintings The First Introduction of Christianity into Great Britain (1842) and Our Saviour Subject to His Parents in Nazareth (1847) were the inspiration for the two most important early works by William Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais, the founders of Pre-Raphaelism. The two artists were the authors of the paintings A Converted British Family Sheltering a Christian Missionary (Hunt) and Christ in the House of His Parents (Millais), which were exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1850 to great controversy. But Herbert used his position in the Academy to help the two artists.

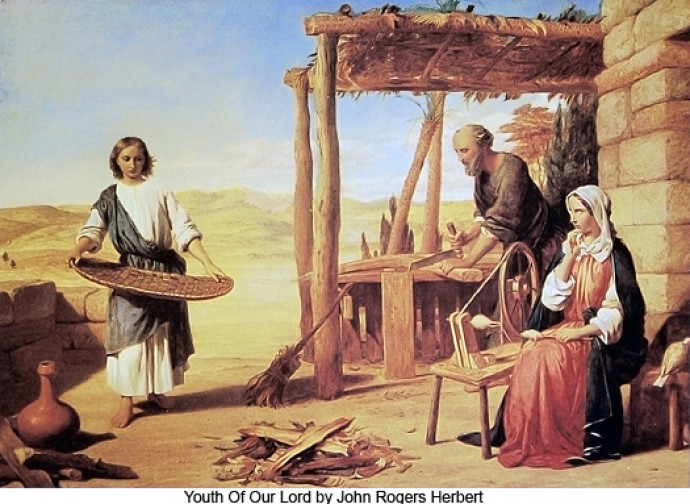

But let us focus on the above-mentioned painting, Our Saviour Subject to His Parents in Nazareth, which depicts Jesus as a teenager in His parents' house in Nazareth. The atmosphere of the painting is very serene, the colours suggesting those of the Holy Land (shades of terracotta, straw yellow and a limpid sky on the horizon). Jesus, barefoot, is busy carrying a wicker basket, while Mary is unravelling wool with a wooden wheel and spindle. A random arrangement of wood in the shape of a cross on the unlit fire catches the young Jesus' attention; Mary looks at him with concern while Joseph works on unaware.

There are two other versions of this composition, in which the background was based on 'a very accurate drawing made in Nazareth'. The work is housed in the Guildhall Art Gallery (see here), which brings together works of art from the City of London. The same Gallery also owns other works by Herbert, which were reproduced several times already in the 19th century (using the then newly invented process of lithography), making them popular, widely known works.

Although his works often depict the Holy Land, the artist was never able to visit it, which he greatly regretted. He worked from his imagination, inspired by books and conversations with those who had been there. For him, everything served to evangelise: not only his art, but also his person. With a dark complexion and piercing black eyes, he grew a long white beard that gave him a hieratic appearance that did not go unnoticed. Many observers claimed that he had the appearance of a saint. He was strict in his judgements and never compromised, a good storyteller who inspired those who heard him speak, an excellent verbal duellist when it came to defending Catholicism, which he did with conviction, whenever the opportunity arose.

Although his works often depict the Holy Land, the artist was never able to visit it, which he greatly regretted. He worked from his imagination, inspired by books and conversations with those who had been there. For him, everything served to evangelise: not only his art, but also his person. With a dark complexion and piercing black eyes, he grew a long white beard that gave him a hieratic appearance that did not go unnoticed. Many observers claimed that he had the appearance of a saint. He was strict in his judgements and never compromised, a good storyteller who inspired those who heard him speak, an excellent verbal duellist when it came to defending Catholicism, which he did with conviction, whenever the opportunity arose.

Herbert can inspire us too, with his unshakeable faith, developed in a difficult century. It was the century of Cardinal Newman and his conversion (which worried even Queen Victoria): a century when it was difficult to be Catholic in England. Yet there were brave men, like Herbert, who used all the means at their disposal to spread the Word.

Which is what we should do too.