Honey and candles: symbols of taste, health and virtue

There is one thing that almost all abbeys produce: honey, the most ancient and traditional sweetener, a mainstay in cookery, in health promotion, and in candle-making, in recipes like those of Saint Hildegard. The bee, compared to the Virgin Mary in the Laus Apium, is therefore dear to monasticism because of the religious quality of its rigorous behaviour and its intelligent and incessant work.

- THE RECIPE: ROASTED PEAR SALAD WITH HONEY AND GORGONZOLA

It is true that many abbeys produce wine, others excellent beer; there are also monasteries that specialise in jams, and convents that bake biscuits.

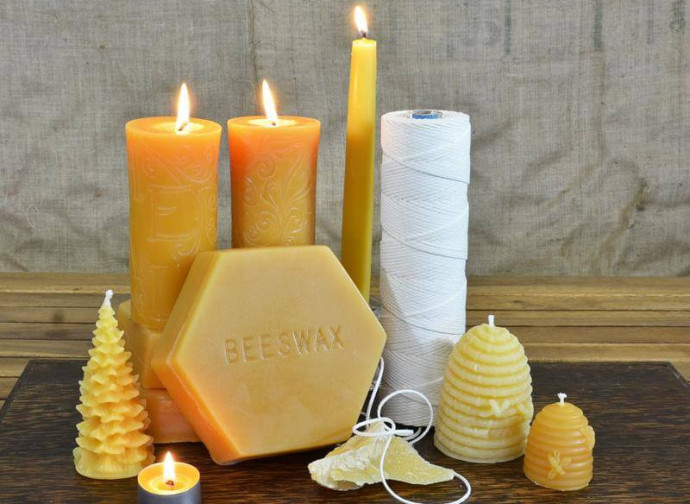

But there is one thing that (almost) all of them produce: honey. Not only because it is the most ancient and traditional sweetener, but because it is the raw material for making tapers and candles, objects that have been used in religious rituals for thousands of years. And also because the bee, such a complex and fascinating creature, mysterious and unique, displays a religious quality in its rigorous behaviour and incessant work.

It is worth mentioning here the Laus Apium (Praise of Bees), which, in spite of the errors, finds a similarity between the bee and the Virgin Mary: “The bee is superior to all other living beings that are subject to mankind. Though very small in body, it nevertheless carries noble intentions in its tiny chest; weak in strength but strong in ingenuity. After having explored the cycle of the seasons, when the freezing winter has stopped whitening and then the moderate climate of spring has swept away the glacial torpor, it immediately feels the urge to go out to work; and the bees scattered in the fields, gently hovering on their wings, barely touch down with their nimble claws to harvest the small flowers of the meadow with their mouths, laden with food they return to their hives and here some with inestimable art build small cells with tenacious wax, others store the fluid honey, others transform the flowers into wax, others give shape to their young by licking them with their mouths, others store the nectar of the collected leaves. O bee truly blissful and admirable, whose sex is not violated by males, nor perturbed by foetuses, nor whose chastity is destroyed by children; just as, in her holiness, Mary gave birth a virgin and remained a virgin”.

It is worth mentioning here the Laus Apium (Praise of Bees), which, in spite of the errors, finds a similarity between the bee and the Virgin Mary: “The bee is superior to all other living beings that are subject to mankind. Though very small in body, it nevertheless carries noble intentions in its tiny chest; weak in strength but strong in ingenuity. After having explored the cycle of the seasons, when the freezing winter has stopped whitening and then the moderate climate of spring has swept away the glacial torpor, it immediately feels the urge to go out to work; and the bees scattered in the fields, gently hovering on their wings, barely touch down with their nimble claws to harvest the small flowers of the meadow with their mouths, laden with food they return to their hives and here some with inestimable art build small cells with tenacious wax, others store the fluid honey, others transform the flowers into wax, others give shape to their young by licking them with their mouths, others store the nectar of the collected leaves. O bee truly blissful and admirable, whose sex is not violated by males, nor perturbed by foetuses, nor whose chastity is destroyed by children; just as, in her holiness, Mary gave birth a virgin and remained a virgin”.

The most ancient testimony of actual beekeeping dates back to an Egyptian painting of 2400 BC. Egyptian beekeepers used to move along the Nile with their hives to follow the flowering of the plants. When the hieroglyphics were deciphered it became clear that various recipes based on honey were used not only in food, but also as medicines, for the treatment of digestive disorders and for the production of ointments for sores and wounds.

Honey in Ancient Egypt was initially a luxury food and was a royal and divine prerogative. Later, in the second millennium B.C., its use became widespread, a fact demonstrated by the discovery of honey pots or combs in private tombs. Furthermore, honey is mentioned as a food-ration during journeys, as spoils of war, payment of tributes, offerings in temples and votive gifts.

The Sumerians used it in creams mixed with clay, water and cedar oil, while the Babylonians used it for culinary purposes: small focaccias made with flour, sesame, dates and honey were considered a delicacy. The Hammurabi Code contains articles that protect beekeepers from the theft of honey from hives.

The breeding of bees for farming, in order to obtain honey and wax, certainly has a very ancient tradition also in Europe, as testified by Pliny the Elder in Naturalis Historia and by Columella in De re rustica. In 30 B.C., at the time of Emperor Augustus, beekeeping was in its golden age. In addition to the aforementioned Columella and Pliny, Virgil, beekeeper and poet, also dedicated the fourth book of the Georgics entirely to beekeeping, expressing his personal preference for thyme honey.

In Antiquity honey was widely used: the Greeks considered it food of the gods (Aristotle defines it, in his treatise De Generatione Animalium, a substance “falling from the air”): in mythology Melissa, daughter of the King of Crete, fed Zeus with this very food.

Both in Greece and in ancient Rome, honey was used both as a sweetener and as a condiment and a preservative. Homer describes the collection of wild honey, while Pythagoras recommended it as a useful food to prolong life.

The treatise De arte coquinaria by Apicius (actually a collection of several authors covering several centuries) is perhaps the richest source of information on the use of honey in cooking. The recipes of this work show a preference for the sweet and sour taste. As a sweetener, honey appeared on modest tables as well as on those of the rich, where it was sometimes served in the honeycomb in which it was contained. Honey was used in the preparation of fish and legume dishes, fruit jams and syrups, but also of meat, bread and focaccias. As a preservative, it was used with fruits such as apples, pears and quinces. It was also a food given to children of the wealthiest social classes.

From its fermentation, mead was produced, which continued to be popular even in the Middle Ages. Another sought-after drink was honeyed wine, for which the most precious and aged wines were used (Massico, Falerno). But the use of honey extended to cosmetics, where it was used to produce aromatic oils and perfumes; to medicine, where it was used as an antiseptic, vulnerary and purgative; to luxury handicraft: it was an ingredient used to give shine to purple fabrics, and in jewellery to make precious stones shine. It was also used to polish wood, and as a lubricant for doors and drawers.

Saint Hildegard of Bingen also created the first recipe for scented candles: “Mix beeswax with essential oil of orange and ground cinnamon, then make candles to perfume the house and ward off evil spirits”.

Saint Hildegard of Bingen also created the first recipe for scented candles: “Mix beeswax with essential oil of orange and ground cinnamon, then make candles to perfume the house and ward off evil spirits”.

Saint Ambrose, patron saint of beekeepers, was also a passionate beekeeper. Honey still played a central role in the medieval diet, even though reduced compared to its value in Antiquity, because it began to suffer competition with sugar. In fact, honey was gradually supplanted as a sweetening agent in later centuries, especially after the introduction of industrially refined sugar.

Nowadays, however, due to its recognised therapeutic properties, honey is returning in vogue in various forms, both as a food and in cosmetics and natural medicine. And monasteries play a leading role in beekeeping and the subsequent spread of honey products.

In Italy, the monastery of Bose is famous for the production of candles, which are processed entirely by hand: the handmade candle is a unique piece and its value is also unique. In Switzerland, at the Sanctuary of Einsiedeln, the candles that make the Black Madonna shine are produced by the Benedictine monastery itself.

In the United States, in the small town of Saint Benedict (evocative name) in Louisiana, the monks of Saint Joseph Abbey had the idea of using the sponsorship of companies and individuals who “adopt” a beehive and their name appears on it. Here they produce honey, candles and even a soap based on honey and perfumed with essences of flowers, such as St Teresa's Rose: they call it Monksoap.

In the United States, in the small town of Saint Benedict (evocative name) in Louisiana, the monks of Saint Joseph Abbey had the idea of using the sponsorship of companies and individuals who “adopt” a beehive and their name appears on it. Here they produce honey, candles and even a soap based on honey and perfumed with essences of flowers, such as St Teresa's Rose: they call it Monksoap.

In Great Britain, in Devon, there is an abbey (the Buckfast Abbey) that has had an apiary since the Middle Ages and continues to produce honey, candles and cosmetic products.

In Italy we find honey and derived products in several monasteries, convents and abbeys: from the Trappist friars of the Madonna dell'Unione of Boschi, to the Monastery of Vasco (Cuneo); the Convento del Deserto of the Discalced Carmelites in Varazze (Savona); also in the province of Savona, in Finale Ligure, we find the Beekeeping Museum of the Benedictine Aviary; then there are the Cistercian abbeys of Chiaravalle in Milan, Chiaravalle in Fiastra, Sforzacosta (Macerata), and Valvisciolo, Sermoneta (Latina); the Benedictine abbey of Vallombrosa in Reggello (Florence); the Benedictine hermitage of Camaldoli in Poppi (Arezzo); also the Benedictine nuns of San Daniele, in Abano Terme (Padua) and Montevergine (Syracuse) have a beautiful production; the Passionist Sanctuary of the Madonna della Stella in Montefalco (Perugia); the Minor Observant Friars of the Sanctuary of San Francesco da Paola, in Paterno Calabro (Cosenza); the Benedictine nuns of the Monastery of Nostra Signora dell'Annunciazione in Laveno, in the province of Varese, and many other wonderful places (I apologise to those who are not mentioned).

Bees, honey, and wax: beauty, goodness, and spirituality. Bees embody a gentle message of “ora et labora”. Honey sweetens not only food, but also life. While candles accompany us on our journey: light, warmth and hope are the elements that symbolise the Christian Church. Our Church.