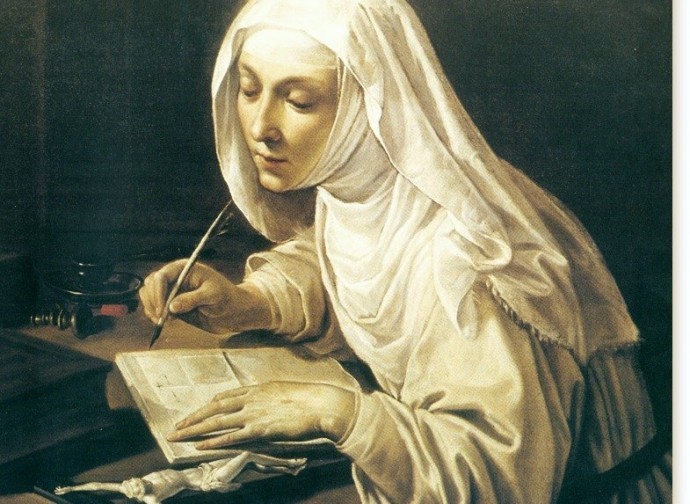

Catherine of Siena, a saint who craved love and justice

Determined to do God's will, Catherine overcame various difficulties in her family in order to join a religious order. Finally she was accepted into the Mantellate, Dominican tertiaries. She helped her fellow human beings and wrote over three hundred letters, assisted by the 'beautiful brigade'. She fought to bring the Pope back to Rome, offering continuous fasting and penance, until she returned to the Father at the age of 33.

- THE RECIPE: CRESPEOU D'AVIGNON

The kitchen was filled with scents, vapours, and voices. Large wax candles, taller than a man, sent a wavering light across the high vaulted ceiling. The cook's helpers ran from station to station, some plucking chickens, some overseeing sauces, cleaning vegetables, and arranging cheeses on large trays. The cook is perplexed, His Holiness has invited some Italians who are passing through for dinner; with them there is a nun who has said that she will eat nothing but some vegetables. He, who is the best cook in France, has to cook vegetables? He scratches his head indecisively: it's almost an insult to a master of the kitchen like him. He decides that he will make a vegetable dish, but in his own way: he will make the best crespeou that the nun has ever eaten: it is the typical dish of Avignon (see recipe). He will prepare it himself.

The cook is Bastien Le Gaillou, chef in the kitchens of Pope Urban V (1310-1370). The nun is Catherine of Siena and we are in Avignon, in 1367. Catherine is twenty years old, but she looks older. With her severe and strong-willed face, her charisma, her decisive voice, and her soul-searching gaze, Catherine is intimidating. From a young age she has asserted her own will, from the day she told her parents she wanted to become a nun, going against their wishes.

Catherine was the last of twenty-five children, born in Siena in 1347, in the district called Contrada dell'Oca, the daughter of a family who belonged to the common people. Her father, Iacopo di Benincasa, was a dyer; her mother, Lapa di Puccio di Piagente, was his second wife. From a very young age she was inclined towards a mystical-contemplative life. At the age of six, in the Sienese town of Vallepiatta, she had a supernatural vision of Christ giving his blessing. She was so impressed by it that she devoted herself to ascetic practices and made a vow of virginity: this was the first of a long series of mystical experiences. At the age of twelve, her parents thought of marrying her off, but Catherine, after an initial period of hesitation, decided that she would take the veil.

Her biographers’ accounts agree on the difficulties the young girl had to overcome in her family, where attempts were made in vain to induce her into a “worldly” life. Finally, she managed to obtain a sort of domestic cell in her father's house, where she spent about three years of ascetic and meditative life. At the age of sixteen Catherine was illiterate, but with her characteristic will she overcame this obstacle. She learned to read and write, not only as an autodidact, but also under the influence of her confessors and spiritual guides, all Dominicans: the Florentine friar Angelo degli Adimari, the Sienese friar Tommaso della Fonte - Catherine's acquired relative - and subsequently friar Bartolomeo Dominici, who was the first to perceive her ingenuity and lively spirituality.

An admirer of the Mantellate (an association of pious women who were widows), she had always wanted to join their ranks. But she was a virgin and very young, so the Mother Superior refused to admit her. Catherine did not give in and finally managed to convince her. And so it was that the young girl took the habit of the Dominican tertiaries. She was the first virgin to join; it was either the end of 1364 or in 1365.

Catherine was not made for a cloistered life, but was attracted by the needs and affairs of her fellow human beings, and the possibility of helping them in a Christian way. It is not by chance that the so-called “family” or “beautiful brigade” spontaneously formed around her: a few dozen people, deeply religious and of a certain culture and doctrine, all animated by the same ideal of life, according to the spirit. The group was not organised in a clerical manner, but was united in quite an “emotional” way to Catherine - the “mother” - who in turn was very close to them, as numerous letters from her show. The members were men and women, both lay and religious, from all over the city. Of special importance in this cenacle were four or five lay people, who can be considered secretaries of the saint and who were especially close to her, as experts in writing under dictation, since this was the method Catherine used more than any other to write letters. Almost all of them were of noble extraction and from Siena: Neri di Landoccio de' Pagliaresi, then Stefano di Corrado Maconi, Francesco di Vanni Malavolti, then the Florentine Barduccio di Piero Canigiani, and, another Sienese, Cristofano di Gano Guidini, who was particularly suited to act as secretary since he was a notary by profession. As such he had at his disposal parchment, quality paper, and almost indelible ink: the documents he compiled have suffered very little from the ravages of time precisely because of the quality of the media and writing instruments.

Catherine was not made for a cloistered life, but was attracted by the needs and affairs of her fellow human beings, and the possibility of helping them in a Christian way. It is not by chance that the so-called “family” or “beautiful brigade” spontaneously formed around her: a few dozen people, deeply religious and of a certain culture and doctrine, all animated by the same ideal of life, according to the spirit. The group was not organised in a clerical manner, but was united in quite an “emotional” way to Catherine - the “mother” - who in turn was very close to them, as numerous letters from her show. The members were men and women, both lay and religious, from all over the city. Of special importance in this cenacle were four or five lay people, who can be considered secretaries of the saint and who were especially close to her, as experts in writing under dictation, since this was the method Catherine used more than any other to write letters. Almost all of them were of noble extraction and from Siena: Neri di Landoccio de' Pagliaresi, then Stefano di Corrado Maconi, Francesco di Vanni Malavolti, then the Florentine Barduccio di Piero Canigiani, and, another Sienese, Cristofano di Gano Guidini, who was particularly suited to act as secretary since he was a notary by profession. As such he had at his disposal parchment, quality paper, and almost indelible ink: the documents he compiled have suffered very little from the ravages of time precisely because of the quality of the media and writing instruments.

It can be said for certain that Catherine benefited greatly from the cultural side of her uninterrupted familiarity with them. In any case, in the year our story begins, 1367, Catherine is in Avignon, the papal seat, to persuade Urban V to return to Rome. Urban listened to Catherine's appeal and returned to Rome that same year. But the truth is that the pontiff was more worried about the Hundred Years' War veterans heading for Avignon than about divine vengeance. The proof: as soon as the situation in France stabilised, the Pope returned there.

1374 was a very important year for Catherine because she came into direct contact with Gregory XI. Shortly before Palm Sunday (26 March), she wrote, from Siena, to Bartolomeo Dominici and Tommaso Caffarini, that the Pope “has begun to cast his eye towards the honour of God and the holy Church”, by sending her the Spanish prelate Alfonso di Valdaterra, who had already been confessor to Saint Bridget of Sweden (who died on 23 July of the previous year), to invite her to say a “special prayer” for the pope and the Church, “and as a sign he brought me the holy indulgence”. It can be assumed that this mission had an exploratory purpose and was desired by the Pope himself, who wanted to obtain reliable information about the Sienese Mantellata, whose fame had certainly reached him (perhaps accompanied by comments and rumours that were not exactly benevolent). And it may also be that he intended to use her for a very special and challenging task: that of taking over from the Swedish visionary as “revealer” of God's will, especially in relation to the difficult question of leaving Avignon and returning to Rome. Of course Catherine did not fail to write to the Pope placing herself at his disposal, but she also took the opportunity to recommend the cause of the crusade, the 'holy passage'. But that letter has not come down to us.

Gregory XI returned definitively to Rome on 17 January 1377. He died the following year and was succeeded in April by the archbishop of Bari, Bartolomeo Prignano (1318-1389), who decided to take the name of the man who strongly intended to remain in Rome: Urban VI. The cardinals, the majority of whom were French, regretted having elected as Pope a man who was motivated by the desire to end the period of the Avignon papacy, and in September they appointed another: this time they elected Cardinal Robert of Geneva (1342-1394), who took the name of Clement VII and took office in Avignon in June 1379.

Thus the Christian world had a Pope and an antipope, who excommunicated each other. The Church was split. Catherine suffered greatly and expressed her suffering by completely stopping eating and drinking, and by piercing her flesh with nails similar to those used on Jesus on the cross. In addition, she did not sleep more than two hours per night. She died on 29th April 1380, at the age of 33, exhausted by penances, distressed by her own failure, with both Christian sides fighting each other, and invoking God with the last breath she had in her frail body. Her funeral was celebrated by Urban VI. She was buried in the Basilica of Santa Maria Sopra Minerva in Rome.

Catherine left an epistolary of 381 letters, a collection of 26 prayers and the Dialogue of Divine Providence. Many of her works were dictated, although Catherine was able to write (and wrote) some letters in her own hand. At her death her disciples collected her letters. The theologian Thomas Caffarini, in charge of the negotiations for Catherine's canonisation, was the author of the collection that is considered official. The Letters were immediately a great success. The editio princeps, edited by Bartolomeo Alzano, was printed by Aldo Manuzio in Venice in 1500. The collection, comprising 353 letters, was reprinted several times during the 16th century. In the 1860 edition, Niccolò Tommaseo attempted to restore chronological order to the letters and provided them with an apparatus of notes that was much appreciated by scholars from both a historical and a linguistic-literary point of view.

Catherine left an epistolary of 381 letters, a collection of 26 prayers and the Dialogue of Divine Providence. Many of her works were dictated, although Catherine was able to write (and wrote) some letters in her own hand. At her death her disciples collected her letters. The theologian Thomas Caffarini, in charge of the negotiations for Catherine's canonisation, was the author of the collection that is considered official. The Letters were immediately a great success. The editio princeps, edited by Bartolomeo Alzano, was printed by Aldo Manuzio in Venice in 1500. The collection, comprising 353 letters, was reprinted several times during the 16th century. In the 1860 edition, Niccolò Tommaseo attempted to restore chronological order to the letters and provided them with an apparatus of notes that was much appreciated by scholars from both a historical and a linguistic-literary point of view.

Catherine of Siena had a strong influence on at least two other great saints, Rose of Lima (1586-1617) and Kateri Tekakwitha. Catherine of Siena was canonised by Pope Pius II of Siena in 1461. In 1866 Pius IX wanted her to be counted among the co-patrons of Rome. Paul VI proclaimed St Catherine Doctor of the Church on 4 October 1970. The beautiful homily that Paul VI gave on that occasion (3 October 1970) is a perfect summary of what Catherine was and represented:

“You all know how she was free of all earthly cupidity […], how she hungered for justice and was filled with mercy as she strove to bring peace to families and cities which were tom by rivalries and atrocious hatreds, how she did wonders to reconcile the Republic of Florence with the Supreme Pontiff Gregory XI, and even went so far as to expose her life to vengeance from the rebels. […]”

We will certainly not find in the Saint's writings, that is in her Letters, preserved in a very conspicuous number, in the Dialogue of Divine Providence or Book of Divine Doctrine and in the Orationes, the apologetic vigour and the theological daring that distinguish the works of the great luminaries of the ancient Church, both in the East and in the West; nor can we expect from the uneducated virgin of Fontebranda the lofty speculations, proper to systematic theology, that made the Doctors of the scholastic Middle Ages immortal. And if it is true that her writings reflect, to a surprising extent, the theology of the Angelic Doctor, it appears there, however, stripped of any scientific coating. What is most striking about the Saint is her infused wisdom, that is, her lucid, profound, and intoxicating assimilation of the divine truths and mysteries of the faith contained in the Sacred Books of the Old and New Testaments: an assimilation favoured, yes, by singular natural gifts, but evidently prodigious, due to a charism of wisdom of the Holy Spirit, a mystical charism.