Accompany without conversion: Belgian bishops' like the Germans

The ad limina visit is now the pretext to endorse the overturning of faith and morals accompanied by (Roman) pats on the back. To clear the way for the blessing of homosexual couples, Cardinal De Kesel relies on the words of Philippe Bordeyne, president of the John Paul II Institute, in the name of an openness to everything – except conversion.

For some time now, the ad limina Apostolorum visits seem to have become a sort of showcase for the bishops to relaunch in the mass media their willingness to persevere in the reversal of faith and morals. A community outing to Rome with a nice chat with the Pope, who would seem to give a pat on the back each time to confirm the most disparate pastoral choices. The German bishops went home saying that the pope encouraged them to keep the tensions alive (see here) while shrugging off Cardinal Oullet's request for a moratorium on the Synodaler Weg documents.

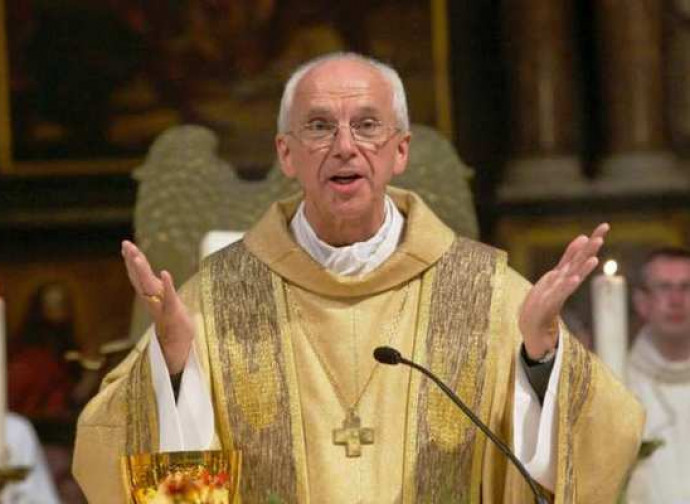

Barely a week later, it’s the turn of the bishops of Belgium, also delighted to have a cordial dialogue with the pope, after some of them, namely the Flemish bishops, had approved a rite for the blessing of same-sex couples (see here). Actually, the ad limina visit was scheduled for the end of September; it is not clear whether this liturgical initiative suggested to the Holy See that it was more prudent to postpone it by a few weeks. Cardinal Jozef De Kesel, president of the Belgian Bishops' Conference, said (see here): "We talked about homosexual couples, we talked about viri probati, we talked about the possibility of the diaconate for women”. No mention of the appalling reduction in priestly ordinations and Catholics attending Mass and receiving the sacraments.

On the blessing of gay couples, De Kesel explained that "what we wanted to do was to slightly restructure the pastoral care, so that in each diocese, within the family pastoral team, there is someone who deals with the problem. In Rome we were able to talk about it and we felt listened to: this does not mean that my interlocutor necessarily agrees with me, but we were able to discuss it. We must help these people, if we don't help them they are lost”. And evidently the creation of a liturgy for the occasion is a way of taking care of the problem in a limited way.

In case it occurs to the benevolent reader to interpret the prelate's pastoral concern in the most chaste way possible, De Kesel himself dispels any doubts about what is meant by pastoral care for homosexual couples: "Can one ask these people to live in chastity? One must be realistic...”. And he adds: “I have read a position on the matter by the president of the Pontifical John Paul II Institute for the Family, Monsignor Phlippe Bordeyne, according to whom no one can be deprived of God's blessing”. We will return to this in a moment.

The Flemish Cardinal also takes the opportunity to lobby again on the issue of ordaining married men, "not to change the discipline of the Church, celibacy; but in certain situations why say no to viri probati?" Now, the least that can be said is that De Kesel fails to see the logical contradiction in his statement; for to allow the ordination of viri probati is precisely to change the Church's discipline on celibacy.

And then, inevitably the female diaconate: “according to historical, theological, exegetical studies, it seems that the female diaconate has existed, and even with the laying on of hands, as a ministry: it cannot be denied”. Once again, the cardinal seems not to notice the blatant contradiction in his statement: if it 'seems' that there was a female diaconate, why then 'it cannot be denied'? Does it seem or is it certain? And the evoked laying on of hands, what value did it have? Are there perhaps testimonies of deaconesses performing the same liturgical ministries as deacons?

Let us return to the blessing of homosexual couples. The president of the Belgian Bishops' Conference recalled a statement by Philippe Bordeyne, who, just a week before the visit of the Belgian prelates to Rome, had ‘coincidentally’ reopened the possibility of this blessing. Bordeyne clearly distanced himself from last year's Responsum of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, in which it was explained that the Church does not have the authority to impart blessings to same-sex unions, since “what is being blessed” must be “objectively and positively ordered to receive and express grace, in accordance with God's designs inscribed in Creation and fully revealed by Christ the Lord”. These unions are not.

Instead, the president of the JPII Institute bases his 'openness' on a convoluted assertion of the anteriority of the good with respect to what is right and what is wrong; the blessing would turn to the good, without thereby legitimising an act. Bordeyne relies on the first chapter of the book of Genesis, when God sees the good he has done: “And God saw that it was good”. This text, however, supports the Congregation's position, which explains that it is the blessing of the person, which God ontologically creates 'very good', that is legitimate, and not the homosexual relationship, which is not the result of divine creation, despite claims to the contrary.

Nor does it make any sense to evoke the evangelical figure of Bartimaeus rebuked by the disciples, in order to claim that these couples ask “from God what they could not get from the Church”; or the customary refrain of Jesus eating with sinners, conversing with the Samaritan woman, etc. Once again, this demonstrates the difference between the sinful person and sin, and not the blessing of an objectively disordered union.

Like De Kesel, Bordeyne also shows, in the end, where the real problem lies: one does not have the courage to believe in the work of grace and in the possibility of human beings to change, to correct themselves: “Let’s be realistic: not all people who cannot marry have the ability to live on their own. Are they not entitled to the support of the Church in their journey of faith and conversion? We must have the courage to be pastorally creative”. It goes without saying that the problem is not living alone or not, but the type of relationship that is established. The sixth commandment simply no longer exists.

In the name of 'creative pastoral work' the Church is meant to accompany people along the path either of a selective conversion – i.e. a conversion that only concerns certain aspects of the person and not others – or of a selective faith, i.e. a faith that has decided to erase an entire chapter of God's Revelation. The latter is called heresy; the former, on the other hand, becomes a practice to end up in hell.