Therapeutic liqueurs that encourage “leisureliness”

From phytotherapy came elixirs and then digestifs, imbibed for medicinal purposes - until the FDA banned their sale for this use. Fortunately, today Italy is still the country with the highest number of bitters produced in the world. And for this we owe thanks to the monasteries, convents and abbeys.

- THE RECIPE: NOCINO

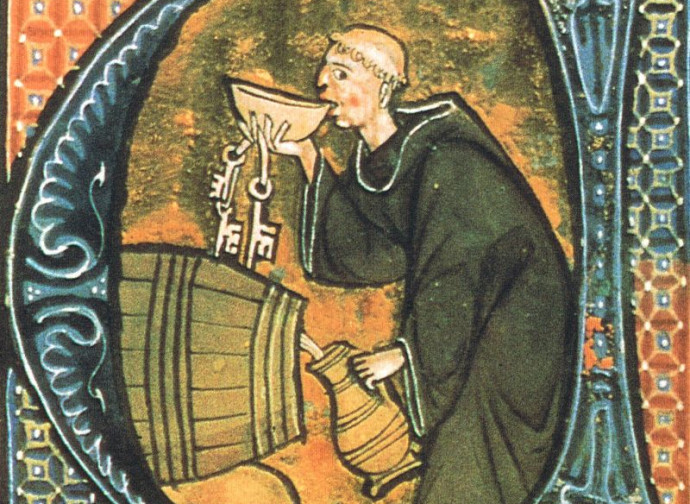

Herbal medicine is a noble and ancient art that has been cultivated and studied in monasteries since the Middle Ages. At that time, monks not only gathered wild medicinal plants, but began to grow them; then they would dry them so that they were always available.

At some stage, however, they discovered that the plants could be preserved for longer by soaking them in alcohol while still fresh. So the monks began to diversify their experiments with different plants and spices, developing potions to cure, tone, and rejuvenate. All parts of the plant were used: leaves, stems, roots, flowers, seeds, and berries. Each part was used to obtain these phytotherapeutic drinks. They called them “elixirs”: there was one for every disease and the final taste depended on the plants used and the length of infusion.

Elixirs are the precursors of the digestifs we know today, especially bitters, developed in a unique way by monastic liquorists. (Although they also existed in ancient times: Hippocrates recommended a bitter prepared with barley, honey and herbs added to wine, to aid digestion of the lavish lunches).

Unlike aperitifs, which are served before a meal and are generally light and dry, digestifs, served at the end of a meal, are higher in alcohol and can be sweet, bitter or even spicy. They can be obtained by maceration of the plants in alcohol, by distillation, or by combining the two processes. The best known digestifs were perfected by monks between the 16th and 19th centuries.

Medicinal digestifs, which are, so to speak, evolutions of the elixirs (created with a merely medicinal purpose), have evolved over time into “society” drinks, sold by the monasteries, but also in pharmacies and herbalist shops. So the bitters were administered as medicines, as stimulants in case of lack of appetite, or as digestifs. But the definition of a ‘bitter’ as a digestive medicine changed in 1906, due to an objection by the American Food and Drug Administration, which decreed that it should be taxed as an alcoholic drink; this led to a fall in sales.

Fortunately in Italy the beneficial properties of bitters continued to be appreciated. In fact, Italy still remains the country that produces the highest number of bitters in the world, ranging from vermouths to liqueurs. And it is all thanks to the monasteries, convents, and abbeys.

The recipe for the medicinal bitter was handed down from generation to generation by the monks. In the IX-X century a real medical school, the so-called “School of Salerno”, was developing, which would see its greatest splendour in the following centuries. Its date of origin is uncertain, but what is certain is that it was born in a monastic environment. In fact, in 820 Archdeacon Adelmo of Montecassino had already founded a hospice for the sick in Salerno, while the infirmary for the monks had already been operating in the same abbey since the time of Saint Benedict.

The digestifs are many and almost all their recipes are more or less secret. One of the closest-guarded secrets is the recipe of Chartreuse, one of the most famous digestifs. According to the history of the Order of the Carthusian monks, who still own the recipe and the brand, it was the Marshal d'Estrées who delivered the original recipe to the monks of the Chartreuse de Vauvert, in Paris, in 1605. But it was the Monastery of the Grande-Chartreuse, in Isère, that took over production in 1737, following the original recipe; this was later improved by the monastery's pharmacist, brother Jérôme Maubec. This formula is still used today by the monks to produce the famous green liqueur, which they also produce in diferent colours.

The digestifs are many and almost all their recipes are more or less secret. One of the closest-guarded secrets is the recipe of Chartreuse, one of the most famous digestifs. According to the history of the Order of the Carthusian monks, who still own the recipe and the brand, it was the Marshal d'Estrées who delivered the original recipe to the monks of the Chartreuse de Vauvert, in Paris, in 1605. But it was the Monastery of the Grande-Chartreuse, in Isère, that took over production in 1737, following the original recipe; this was later improved by the monastery's pharmacist, brother Jérôme Maubec. This formula is still used today by the monks to produce the famous green liqueur, which they also produce in diferent colours.

Bénédictine, produced with the same 27 plants and spices as when it was created in Fécamp Abbey, Normandy, in 1510, is also a digestif known and appreciated throughout the world. In addition to these legendary digestifs, there are some lesser known ones, though they have significant histories. Kylon, for example, is a digestif similar to the Italian Nocino (whose recipe is linked to this article). Kylon is an elixir with digestive and detoxifying properties, the result of a long maceration of fresh green walnuts mixed with thirty-two exotic and alpine plants, among which we find cloves, bitter orange, peppermint, cinnamon, thyme, coriander, marjoram, green anise, lime blossom, chicory root.

The complete list of ingredients is still kept secret by the Brothers of the Holy Family. This congregation has always been present in Belley, France. Expelled from France in 1903, the Brothers of Belley had to move to the neighbouring country, Italy. Only a few elderly and sick Brothers remained in Belley, where they survived for a long period of 35 years, until 1939, when the exiled Brothers also returned to the country, some to be recruited, at the beginning of the Second World War. Over the years, the Congregation developed in other countries on different continents. And they continued to produce their digestif.

In terms of production, there has been minimal or no change. The distillery still extracts the nutrients from the plants in steam stills. And after six months of maceration the time comes for a long period of ageing in oak barrels. The only thing that has changed is the creation (in the Sixties) of an identical non-alcoholic drink called Kario Kylon – Greek for walnut extract - while the original Kylon recipe has an alcohol content of 23°. In the old days, alcohol was necessary to stabilise the recipe, whereas today pasteurisation enables the production of a non-alcoholic drink while preserving most of the active nutrients of the plants.

Other monasteries and abbeys produce a wide variety of digestifs. Some began back in the 18th century, others more recently, taking advantage of the enthusiasm that monastic beverages have always aroused. The monks and nuns of Lérins, Sénanque, Sainte-Marie-du-Désert, Vallombrosa, Monte Senario, Orte and many other places, continue to produce digestifs, some of which are centuries old, others more recent, in the purest tradition of their respective orders, custodians of a magnificent heritage that many people envy.

Other monasteries and abbeys produce a wide variety of digestifs. Some began back in the 18th century, others more recently, taking advantage of the enthusiasm that monastic beverages have always aroused. The monks and nuns of Lérins, Sénanque, Sainte-Marie-du-Désert, Vallombrosa, Monte Senario, Orte and many other places, continue to produce digestifs, some of which are centuries old, others more recent, in the purest tradition of their respective orders, custodians of a magnificent heritage that many people envy.

There is even a distribution company, Terra in Cielo (terraincielo.it) which in its rich catalogue sells the products packaged by the religious of over 50 monasteries, abbeys and convents, mostly in Italy, but also in France, Belgium, Austria and Holland. Currently there are eight hundred products in the catalogue, including beers, wines, honey, candies, natural remedies and other delicacies, all strictly natural.

All digestifs are based on alcohol (spirit) as the main ingredient, which is then flavoured and sweetened. The base is often a neutral spirit, but it can also be a renowned alcoholic drink, such as Scotch whisky used to make Drambuie, or cognac used to make Grand Marnier. The list of ingredients used for flavouring is endless, limited only by the imagination of the liquorist. But many ingredients believed to have medicinal properties have a bitter taste. This is the case with plants such as gentian, angelica and cinchona, for example, known to stimulate digestive functions.

Bitters are certainly the closest to real digestifs. They are numerous - hundreds in Italy alone - and offer a wide range of flavours. Some are sweeter and easier on the palate, although they are still noticeably bitter. Others are extremely bitter and must be “tempered” (with a little water, or better still, with ice cubes). And this is how drinks designed to cure illnesses become “society drinks”.

Digestifs may not have the digestive virtues attributed to them, but the “ritual of the digestif” deserves attention. Ending the meal with a digestif prolongs the pleasure of dinner and the company of friends, of the evening, and of conversation. To relax, chat, and laugh. To savour time. There is something leisurely about digestifs. We never drink them fast. We taste them, we savour them, we linger over them. Perhaps this is their curative virtue: they encourage leisureliness. And there is nothing like the leisurely flowing of time to aid digestion.