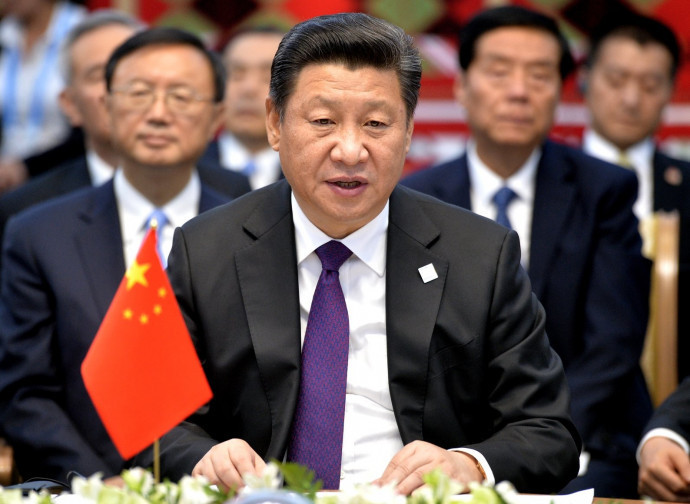

The real problem with the coronavirus is the Chinese regime

Xi Jinping has made a Maoist-style announcement of a “war of the people” against the coronavirus, in order to impress international public opinion. The Chinese authorities are now declaring that the contagion can be spread through paper money: the material of science fiction novels. The door has been opened for the communist party to use brutal means of repression against the people, along with other devices. Does the West really have no objection?

How can the constant spread of cases of the coronavirus pneumonia be stopped? The Chinese President Xi Jinping has no doubts: with a war – actually “the war of the people.” It seems like a return to Maoist times: the Chinese communist leader has called the Chinese nation to a great popular mobilisation, placing in motion the entire mechanism of the State, the health-care industry, the military, and also the structures of the One Party in order to defeat the threat of the virus.

Such a show of muscle seems primarily aimed at impressing international public opinion, which is looking with growing concern at the numbers of those infected as well as the dying, which is constantly increasing. For, as we now know, cases of the new pneumonia outside of China are sporadic, linked exclusively to cases where people with the virus have gone outside of China’s borders.

However, according to the Chinese authorities, there may be a way that the virus is being spread that does not involve direct contact between persons: through paper currency. The vice-governor of the Central Bank, Fan Yifei, announced that all paper money is being placed in quarantine for 10-14 days and being disinfected: all the bills will be cleaned with ultraviolet rays and high temperatures and then sealed. After the time of “quarantine,” the length of which will depend on how serious the epidemic is, the bills will be returned to circulation. Many people throughout the nation are already opting to buy things online.

This news is truly interesting, for many reasons. Banknotes, which pass from one hand to another, and thus can effectively become a receptacle for microorganisms, have never before been the object of medical attention and have never been considered as the means of transmission of illnesses, except for in a suggestive science-fiction novel by American writer Frank Herbert, who is also the author of Dune.

In Herbert’s novel The White Plague, an Irish-American scientist, who has seen his entire family killed in a terrorist attack, decides to take revenge on humanity’s cruelty by spreading a lethal virus through paper money that he contaminates. It is a terribly effective idea, because nothing circulates as widely and rapidly as banknotes. It now seems that the Chinese are taking the hypothesis of this science fiction novel seriously, but the results could be equally worthy of scenarios in a dystopian novel: the sequestering of a huge amount of money, total and absolute control of expenses and consumption by means of the traceability of virtual money, and perhaps even the total elimination of paper currency, all based on hygienic-sanitary pretexts.

This too can be considered part of the so-called “war” declared on the coronavirus by the communist party and the Chinese state. What’s more, the means already being employed are quite drastic: the entire Hubei province, the epicentre of the epidemic, is now confined in a straitjacket of military control, with the use of force authorised and being carried out against anyone who opposes it.

The famous hospitals that were constructed in a matter of days, which the regime boasted about to the whole world (and led some of us also to express admiration for “Chinese efficiency”) are now being revealed, thanks to the communications of neutral observers, as truly horrible, something that makes the memories of the old plague victims pale in comparison. Even if it is not impossible to build such huge buildings in a few days without the forced labor of thousands of workers, something much more is needed for them to truly become hospitals: equipment, medical apparatus, and above all medical personnel and nursing staff who are properly equipped. But all this has not happened. According to scientist Steve Mosher, president of the Population Research Institute, who is monitoring the Chinese epidemic with great attention, these hospitals are in reality, simply huge camps of sick people lying on beds.

But what are the isolation measures that have been enforced to contain the epidemic really like? They are brutal, inhuman measures, motivated by the pragmatic communist vision of the “collective good” that prevails over the good of the individual. This would explain the soaring mortality rate of the last few days: not being able to really win the “war” with pharmaceutical means that are now being proven ineffective, the solution is to isolate the sick. As was done with plague victims in Europe during the much-reviled Middle Ages.

The West seems to have no objection in the face of these coercive measures because there is so much fear that the virus may spread to Europe or other continents. A panic is being created even though we still don’t know how contagious the virus may be. The mortality rate continues to be around 2%, and this concern seems to make everyone close their eyes to everything else the communist party is doing. The great worldwide fear is that the virus will not find any obstacles to slow its path.

For this reason, Western public opinion, driven by complacent media, seems not to be concerned about the means being used by the regime in its war against the coronavirus in order to reach its goal of success. And all this may also reveal a great propaganda operation: China will show to the world that it is capable of defeating even the most threatening epidemics, and it will even be able to boast of having efficiently kept watch over the security of the world. The communist regime will then receive thanks and congratulations, and perhaps the World Health Organization will propose the “Chinese model” as an example to imitate. Which would include the occasion to be pleased with various collateral successes, such as promoting the development of vaccines that will impede other future fears.

Beyond hypotheses, suspicions, conjectures, and imaginary scenarios, or better, coming developments, if – as seems probable – this epidemic proves to be a seasonal flu that ends when temperatures rise and spring comes, there remains the fact that the entire coronavirus operation involves huge amounts of economic, scientific, and human resources. These resources could surely be better invested in efforts to prevent and cure other already-existing epidemics, which claim and impressive and terrible number of victims each year, but which do not make the news, are not on the front pages, and do not evoke scenes from science-fiction stories, but are a tragic reality for millions of suffering human beings.

The real challenges for epidemiology and medicine do not come from potential future pandemics but from actual present ones, which also have a long history behind them: challenges both ancient and new, battles which still have not been won, even if they should have been a long time ago.