Teresa of Ávila and Castilian cuisine

Despite the universal character of her work, the life of Saint Teresa began and ended in the same place, the region of Castile and Leon. A place known for its quality wines, the variety of sweets, its roasts, cold meats and cheeses. Simple but delicious dishes, from the Chuletón de Avileño to the Conejo escabechado. The Carmelite reformer herself, although very austere, loved good food and rewarded her sisters with sweets that became known as Yemas de Santa Teresa.

The year is 1576. Brother Juan de la Miseria, a Carmelite who came from the region of Abruzzi in Italy (his real name is Giovanni Narducci), is standing in front of his easel. His nimble fingers are putting the finishing touches to the portrait of the woman sitting on a wooden chair in a bare room of the Carmel of Ávila. The woman is a nun and intimidates him; he has mixed feelings for her, of veneration and filial affection. But Juan is determined to finish the painting, despite the criticism that the nun has not spared him over all this time, almost a month, since they agreed to painting the portrait, and for which he has gone to the monastery every day, for two hours a day. Now that the portrait is almost finished, Juan is a little sorry. He will no longer come here, to this place where silence is a balm for the soul and light is a gift for a painter. He will no longer listen to the words of the nun, from whom he has learned so much in this short time: while she poses for him, she either prays the rosary in silence, or speaks to him about God and the human soul.

Brother Juan gives the last brush stroke and turns the easel so that she can see the finished work. The nun gets up and approaches, scrutinising the work. Juan does not know if that expression (furrowed brow, pursed lips) is one of reproach, if she likes the portrait or not. Finally, she smiles and speaks in her unique voice: “God forgive you! You have portrayed me bleary-eyed and old!” She was 61 years old. That will forever be the only portrait of St Teresa d'Ávila painted during her lifetime and is now the most frequently reproduced image on souvenirs. And the saint’s response has gone down in history.

Brother Juan gives the last brush stroke and turns the easel so that she can see the finished work. The nun gets up and approaches, scrutinising the work. Juan does not know if that expression (furrowed brow, pursed lips) is one of reproach, if she likes the portrait or not. Finally, she smiles and speaks in her unique voice: “God forgive you! You have portrayed me bleary-eyed and old!” She was 61 years old. That will forever be the only portrait of St Teresa d'Ávila painted during her lifetime and is now the most frequently reproduced image on souvenirs. And the saint’s response has gone down in history.

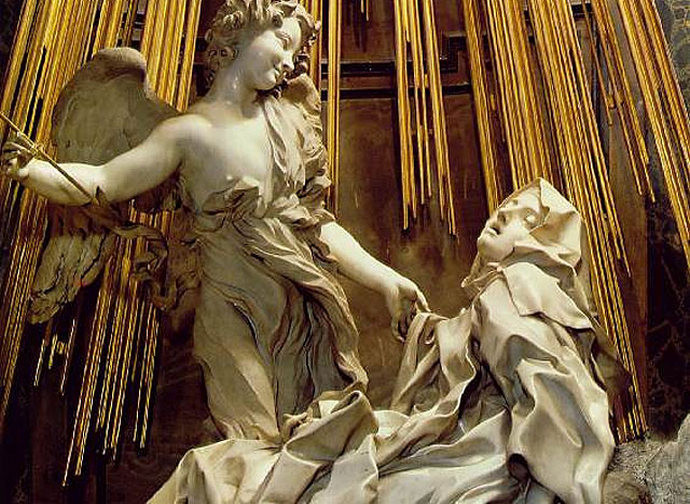

One hundred years later, between 1647 and 1652, another artist, Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680) spent five years of his life sculpting Teresa of Ávila, creating a monumental marble and bronze statue (3.5 metres high) in the collection of the church of Santa Maria della Vittoria in Rome. It took him a long time not only because of the size of the statue, but because the subject was a titanic undertaking: he had to show the ecstasy of Saint Teresa.

How could a human being depict such a thing? Bernini succeeded. And to be precise, it is not an ecstasy, but a transverberation. The work is one of the finest examples of Baroque art, and the artist took professional revenge on Pope Innocent X (1574-1655), who had snubbed Bernini and not entrusted him with any work. But he also had a ‘crush’ on Theresa and this can be seen in the mastery with which he portrayed the ecstasy of the saint. She was undoubtedly a remarkable woman, capable of generating spiritual as well as physical crushes in her contemporaries and beyond. Her charisma and strong personality did not leave those who came into contact with her indifferent.

Her life was out of the ordinary. Teresa (Teresa Sánchez de Cepeda Dávila y Ahumada, 1515-1582) was born into a wealthy family; she had Jewish origins: her paternal grandfather was a Jewish convert. She lost her mother at the age of 13 and from an early age showed an unusual personality, very early on manifesting the two great loves of her life: faith and writing. In fact, she convinced her brother to run away to fight against the infidels and she wrote a chivalric novel with him.

Later, as a grown woman, she was determined, fascinating and captivating, extreme in her choices and at the same time capable of administering monasteries and dealing with the powerful of her time. We are at a time when the Church is in great crisis, beset by deep anxieties, divided and wounded by the preaching of Luther and Juan de Valdés. Teresa was thirty years old at the time of the beginning of the Council of Trent (1545-1563), which represented a stage of reform in the Catholic Church, for the guidance of souls, the foundation of new religious orders, the promotion of a renewed austerity and spirituality. In Spain, King Philip II (1527-1598) championed Catholic orthodoxy. Despite being a great colonial power, Spain experienced a downward parabola. It was in this context that Teresa decided, against her father's wishes, to enter a convent. She ran away from home and entered the monastery of Ávila. This was followed by a period of ups and downs in terms of her health (she suffered from illnesses that were difficult to diagnose and define). Then came the ecstasies. Difficult to explain, except for her: in the state of ‘trance’ that the ecstasies produced, Teresa met God, who spoke to her and gave her various tasks, including the reform of the Carmelite Order.

Throughout the first part of her religious life, she was dissatisfied with the laxity she found in the monastery that initially accommodated her, and her thirst for moral rigour was severely tested. Finally she managed to found a convent, the first of a long series. From the beginning, she was very demanding with her sisters and the various mother superiors of the convents she founded. Her letters are an invaluable document for understanding Teresa's personality, her character, which was anything but easy, but she always spoke out against corporal punishment. She was a severe educator, but at the same time fair and generous. She used to prepare sweets for the other nuns: they are still known as Yemas de Santa Teresa.

Throughout the first part of her religious life, she was dissatisfied with the laxity she found in the monastery that initially accommodated her, and her thirst for moral rigour was severely tested. Finally she managed to found a convent, the first of a long series. From the beginning, she was very demanding with her sisters and the various mother superiors of the convents she founded. Her letters are an invaluable document for understanding Teresa's personality, her character, which was anything but easy, but she always spoke out against corporal punishment. She was a severe educator, but at the same time fair and generous. She used to prepare sweets for the other nuns: they are still known as Yemas de Santa Teresa.

Teresa embraced an austere life that comforted her, lived years of true seclusion and cultivated interior prayer. We are talking about the period in which she often changed confessors - among whom the most famous was another great mystic, St John of the Cross - and of her ecstasies, which remain the most mysterious chapter of her life, which coincided with a time of great spiritual growth and knowledge.

She had a great talent for writing: her mystical texts are among the clearest and most powerful, but also among the most poetic ever written. Her masterpiece is The Interior Castle, which defines the various stages of ecstasy, imagined as seven rooms, representing seven different degrees of closeness to God, up to the soul's union with Him. She is the author of numerous works, biographical, didactic and poetic, which are regularly reprinted throughout the world (here is a rarity: this link allows you to listen to a poem by Saint Teresa of Ávila, Vuestra Soy, set to music).

Paradoxically, the more God entered into communion with her, the more the ecstasies diminished and she achieved, as she writes, true peace, but only within herself, because it was then that the most challenging period of her life began. As mentioned, Teresa received from God the task of reforming the Carmelite Order, which had lost its ancient austerity. The basis of the new rule would be absolute poverty, because a poor order is much freer than one with many earthly possessions.

Teresa spread the reform of Carmel and welcomed the many vocations that were springing up all over Spain and so, no longer young, she left the monastery where she was living and began the difficult work of founding various monasteries. Between 1567 and 1571 she founded convents in Medina del Campo, Malagón, Valladolid, Toledo, Salamanca and Alba de Tormes. The reform she promoted led to the creation of a new branch within the order: the Discalced Carmelites.

Even in her old age she was exposed to the discomfort of travelling and it was while travelling that death seized her. But she had no peace even after her burial: Teresa's uncorrupted body was exhumed several times. Very quickly, her remains proved to be a relic disputed between the convents of Ávila, her birthplace, and Alba de Tormes, her place of death. She now rests in a marble tomb placed in 1760 in the church of the Alba de Tormes convent. Several relics were extracted from her remains and can be found in various churches in Spain.

Teresa was canonised in 1622 and her liturgical feast day is fixed on 15 October. On 27 September 1970 she was declared a Doctor of the Church by Paul VI; she is the first woman to have been awarded this title. Although her spiritual influence, associated with that of St John of the Cross, was very strong in the 17th century, today she remains a reference beyond her monastic family and even outside the Catholic Church.

Despite the cosmopolitan nature of her work, her life began and ended in the same place, the region of Castile and León. A pleasant place, full of beautiful cities, with an extraordinary gastronomic tradition: the region is known for its quality wines, variety of sweets, its roasts, cold meats and cheeses. Simple but delicious dishes: Chuletón de Avileño (similar to Florentine steak), Conejo escabechado (rabbit stewed with wine and vegetables), Morcilla de calabaza (pork with spices and pumpkin), Torreznos (large strips of pancetta fried until crispy), Hornazo (a bread stuffed with chorizo, eggs and pancetta, eaten at Easter), Flor frita (a simple but delicious dessert: flower-shaped dough fried and served sprinkled with sugar). And the list goes on and on.

Teresa herself loved good food: she rewarded her novices by preparing sweets - as we have seen above - and, although she advocated a very austere way of life, she appreciated the joys of the table. There is a famous dialogue between her and St John of the Cross: one day, while they were together for a meal, grapes were served. John said: “I will not eat any because there are too many people who lack food”. Teresa of Ávila replied: “On the contrary, I will eat them so that I can then praise God for these grapes”.

Well said!