Temperance and Prudence: self-regulating people and the economy

Temperance and prudence serve not only to self-regulate our passions, but also to self-regulate economies for production, just distribution and fair pricing. Together the two cardinal virtues help us grow spiritually and seek higher goods, but they do not totally reject bodily pleasures. In fact they help avoid economic blacklisting of pleasurable goods.

While prudence is commonplace, temperance is a very old-fashioned word. Sometimes our words go out of style, because certain circumstances or human behaviours they describe are no longer witnessed or practiced much in human culture. This is especially true when in prosperous, yet consumerist, economies we seldom apply the brakes on our personal desires.

On the one hand, self-restraint is not such a popular virtue when our purchasing power is high. On the other hand shrewd judgement is still quite useful, however, particularly in face of physical danger and moral hazard. Investors are asked to be prudent as are firefighters and police.

Think about it. We are not naturally temperate when in good financial health. It is perfectly natural to consider “why not another” thing or pleasure. So in supposedly in good conscience we think: “Hey friends, why not another drink, I’ve got plenty on my credit card. Why not another Florentine beefsteak, it’s only 50 euros more and besides I am still not that full. Why not another Moto Guzzi, I just got a big bonus and I just crashed my old one.” If we can afford things by way of abundant residual income, then they are justifiable expenses. If there is temptation, we give in to it. So we concede our will to acquire what we immediately desire.

However, when temperance, together with prudence, enter our lives as virtuous consumers, there is no longer a “quantitative easing of our willpower” for “easy spending” on anything and everything. In this case our self-controlled resistance to lower goods (i.e. saying “NO, not another Florentine steak!) must be wedded to hen-pecking, nagging prudence ( thinking “Don’t forget! The extra 50 euro is best for the winter gas bill.”).

Temperance and prudence are the dynamic marriage that animate our Lenten sacrifices that ultimately moderate our use and enjoyment of lower goods so as to focus our intelligence and will on higher goods. They mitigate idolatrous screen time so as to spend more time in Eucharistic adoration and prayerful contemplation. They diminish our thirst for whiskey in order to thirst for sacramental wine. They curb our shopping sprees so as to spring clean our wardrobe and give away our extra clothing to the poor. We become more pious, worship more often, and more charitable.

Of the two, temperance is especially not practiced today since it is vastly misunderstood. We focus too much on the “brakes” – on the powerful will to stop and restrict. No one likes being coerced. Yet, temperance is not about a radical stopping of everything pleasurable. When coupled by prudence it actually validates that “this pleasurable thing is excellent” but only up to certain point or amount or according to a very specific use and purpose. When we accept a wholesale rejection of bodily pleasures, it turns our faith into Puritanism and Gnosticism. These are heresies and, worse still, they have a very ill effect on the market of many goods and services on which much of people’s income depends.

When temperance becomes overzealous by itself it actually rejects God’s own creation and our own creative economic cooperation within it. We reject enjoyment of snow-topped mountains and thus despise the ski resorts, clubs, winter condos and restaurants we build on top of them. We reject enjoyment of the sea, hence we scoff at the yachts and cruise ships we produce to sail on it. We reject viticulture, so we dump out the sumptuous wines sold in beautiful bottles.

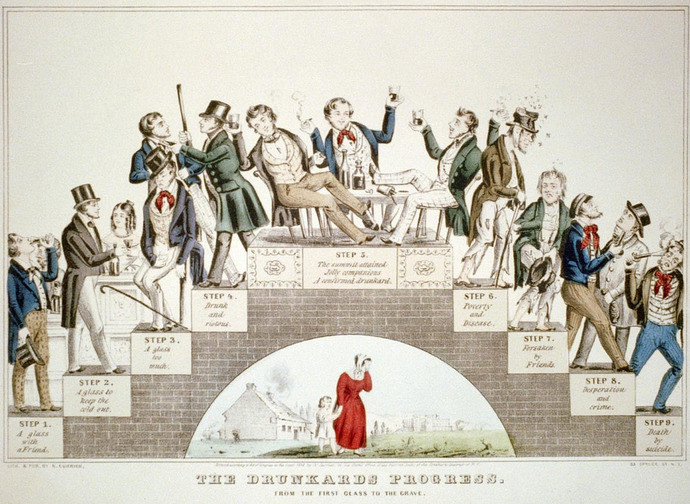

So this, of course, is another fine economic point. Temperance and prudence inform us that the material world is in itself excellent (it comes from God), but not so when used immoderately or for false ends (which comes from vice). Consequently, material goods are grossly misinterpreted as inherently evil and removed from the market. This is what happens with alcohol is not sold in certain “dry” counties and municipalities in America, where public drunkenness and drink-induced violence was once a deep cultural problem and security issue. This was the overreaction behind the American Prohibition in the early 20th century that banned sales of alcohol nationwide. Some material products are evil in themselves, like pornography, and should be removed. But certainly not all material goods.

Finally in crises, as in the one we are presently suffering, we see why temperance and prudence help shape our moral and economic culture. This is particularly the case when seeking to diminish hoarding and prevent artificial price hikes.

When temperance is coupled with prudence, our powerful will resists grabbing packets and packets of toilet paper, among other bare essentials, because our prudent intelligence rejects the “why not another” tendency in us. We rationalize that while we are not poor, others might well be. So we stop grabbing and stuffing our carts. In this way highly sought after retail goods – toilet paper, milk, cheese meat, rubbing alcohol, gloves and masks – are readily available to others. We do our little part to effect distributive justice.

The other fringe benefit of not hoarding is helping to keep prices relatively low when goods are in very short supply while demand is still very high. When very limited bottles of hand sanitizer or masks are snatched up all at once, thousands of local retailers run out their supply and issue massive reorders all at once, overwhelming manufacturers. Often the product comes back at much higher “shock” prices. Why? Reflect on this. Vendors sell with increased price tags often because the rapid resupply of goods from factories often comes with increased costs of production but with much lower volume. This is a double negative.

Factories in crisis economies can’t wait for cheaper boat shipments of raw materials from abroad when reorders for products are urgent, so they purchase the same raw materials locally (but far more expensive) or pay more for shipping by rapid airfreight. Factories can’t shut off the electricity and save when production lines are engineered to run 24 hours a day. Sometimes the sudden stopping and restarting causes severe and far more expensive mechanical damage to mechanical plants, so they don’t risk it. A union-protected workforce can’t be laid off either so easily or paid less, so the manual labor quotient remains invariable.

Furthermore, the warehouses and lorries that factories half fill still have the same lease per month and cost per trip. Now we understand the real economic sin of hoarding, as egotistic consumers place extraordinary stress on factories’ abilities to be efficient, abundant and profitable. The trickledown effect from producers, to wholesalers, to retailer, and finally to eagerly waiting consumers results in high inflation. Crisis economies literally pay a high price because of our irrational intemperance.

Make sense? We cannot pretend that if we hoard, factories will fill their supermarket shelves the very next day with same amount of abundant product and at the same exact low cost of production and thus with the same low pricing as before. In the meantime, I have 20 bottles of hand sanitizer (good enough for a year or two) while my 19 neighbours have none. And everyone suffers in the marketplace.

In summary, temperance and prudence serve not only to self-regulate our passions, but also to self-regulate economies for production, just distribution and fair pricing. Together the two cardinal virtues help us grow spiritually and seek higher goods, but they do not totally reject bodily pleasures. In fact they help avoid economic blacklisting of pleasurable goods. They also help avoid economic bubbles and unwarranted price fixing or rationing by governments. Temperance and prudence keep both persons and economies from imploding and self-destructing. They are more important than ever right now.