Novak: The real global emergency is the falling birth rate

Today, 75% of the world's countries have fertility rates below the replacement level, and it is urgent to reverse this trend to avoid economic and social disaster. In the West today it is not worth it to have children, governments must prevent this discrimination and create an environment favourable to family and life. These are the words of Katalin Novak, former President of the Republic of Hungary and founder of an international NGO dealing with the demographic crisis.

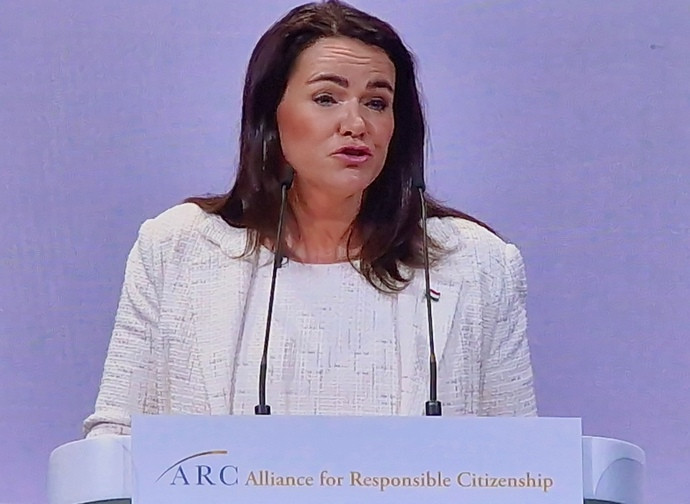

'The demographic collapse is a global emergency and should be at the top of the list of priorities in international relations'. So says Katalin Novak, former Minister for Family Affairs and former President of the Republic of Hungary, where family and birth policies have been very successful over the past 15 years. We met her in London last February at the ARC conference, of which she was one of the organisers, and where she presented the newly formed NGO X-Y Worldwide, which she set up with demographer Stephen Shaw. If it is true that the demographic winter is particularly severe in the developed countries, where the birth rate has been falling for decades, 75% of the world's countries now have fertility rates below 2.1 children per woman, the population replacement level. At this rate, all countries will be at this level by the end of the century, with serious economic and social consequences. The global fertility rate is already 2.2 children per woman, and the UN predicts that it will fall to 1.68 by 2050 and 1.57 by 2100. By then, the world's population will have been declining in absolute terms for at least twenty years.

Katalin Novak, married with three children, the real architect of Hungary's pro-family and pro-birth policies, decided to move from the Hungarian laboratory to global politics after her forced resignation as President of the Republic in February 2024.

Mrs Novak, Hungary is often cited as an example by supporters of pro-family and pro-birth policies. What are the real results of your experience?

I was responsible for family policy for eight years and the results were very positive. When I started in 2010, the fertility rate in Hungary was very low, and in 2011 it reached an all-time low of 1.21 children per woman. Since then there has been a turnaround: the fertility rate has increased by 25%, so it's a great success. In the same years, the number of marriages has doubled and the number of abortions has halved. Unfortunately, the trend was halted by the Covid pandemic and then by the war in Ukraine, with all its economic consequences. However, a pro-family culture has been created which I believe will allow us to get back on track.

However, I am now dealing with these issues on a global level because this is a global emergency and we want to address it as such.

What are you planning to do with your association?

First of all, we do research to understand and explain the reasons for these low fertility rates, then we work on communication and therefore act as advisors to governments, states, local authorities; also to companies, because companies are interested in changing the climate around the decision to have children and better understand the negative consequences of these low fertility rates.

What are the most successful policies in Hungary that you think could be replicated globally?

The decision to have children is not primarily a question of money, but it is also a question of money. In modern societies, from an economic point of view, it is not worth it to have children. It's a harsh statement, but it's true. Having children is very expensive, it takes a lot of time, it takes a lot of energy and there is no economic return. And having children or not having children makes no difference in terms of access to social services. So having children is anything but worth while from an economic and social point of view. That's why we need social and family policies that reduce the economic imbalance between those who have children and those who don't. This means tax relief, housing support, financial support for children's education (such as parental leave); and then other health services for children, support for single-parent families - because we must be aware that unfortunately many families split up - and financial support for those who care for sick children. In addition, it is essential that governments, family associations and companies contribute to creating a mentality that is more favourable to families and children than the current situation.

Many in Europe believe that the solution to the demographic collapse is immigration.

I am well aware of this approach to the problem. Of course, it is up to each country to decide on its own immigration policy, but immigration is certainly not the solution to the problem of falling birth rates. For two reasons: firstly, because it is a global problem and this means that it is a zero-sum game if you move people from one place to another, so nothing changes; secondly, we have to bear in mind that there is an internal demographic gap, which means that on average young couples want to have more children than they actually manage or are able to have; therefore, we in the West have to do what we can to reduce or eliminate this gap and thus help young people to fulfil their desire to be parents.

You have rightly pointed out that the decision to have children is not primarily an economic one, but a cultural one. How can we promote a culture of life?

It is very difficult for a state. That's why I'm happy to be working in a broader field now, because I can also focus on the emotional aspects. I'm a mother of three and I know that having children is above all an emotional decision, not an economic or rational one. But I also believe that it makes a difference to a country facing a low fertility rate whether the fertility rate stays low or rises. Although it shouldn't interfere in personal decisions, it is important that the state encourages parenthood, the time devoted to children, helps those who want to have children and creates a favourable climate, for example by favouring companies that create a family-friendly environment, or local authorities and anyone else who is in favour of families. And it also makes a difference if large families are favoured.

It also depends on the local situation. In Italy, for example, the demographic situation is very negative, and it's really sad to see Italy slipping so much, but even though Italy has very few births at the moment, Italians still have a positive attitude towards children and family life, so you can hope to reverse the trend because you are a family-oriented nation. There is a chance that young people will also realise that family life is something they will miss if they wait too long.

It must also be said that not all births are the same. Today there are those who use the decline in the birth rate as an excuse to promote artificial fertilisation techniques.

I don't want to go into the ethical question, but here too we have to say that assisted fertilisation is not the answer. Infertility problems are mainly caused by delaying the decision to have children. If you decide to have children at the age of 40 or over, it may be too late; the biological clock doesn't follow ideologies.

The problem here is mainly educational; young people need to be made aware that there is a fertility window that must be respected. There is also the problem of increasingly unstable relationships.

But the real solution is to make this problem a priority in global politics and to make young people aware of it. Unfortunately, today this issue is hidden, people only talk about professional success, only individual careers count, and no one is challenged about their personal and family future, how to achieve it. Even if you think you might have children in the future, but you're between 30 and 40 years old and you always say 'yes, yes, but not now, later, because now I have to concentrate on this or that project, I want to finish this school', or there's always something to finish, if you don't stop to think about it, you'll end up never having children.

Birth control, a war against the poor

Contraception, abortion and euthanasia are not conquests of civilisation but weapons in a war against the poor. This is what emerges in a recently published book, Exterminating Poverty by Mark Sutherland. His book tells the story of the legal battle between his grandfather, the Scottish doctor Halliday Sutherland, and Marie Stopes, founder of the first family planning clinic over her eugenic plan to get rid of the poor. The Daily Compass spoke to the author

Britain’s first birth control clinic, 100 years of eugenics and racism

17th of March 1921 Marie Stopes opened Britain’s first eugenic family planning clinic in London. It’s considered one of the greatest humanitarian success of the last century even though the Eugenics Society established the clinic to eliminate the poor and sick. Critics are urging for a debate on the influence eugenics has had on birth control programs currently in use because under the slogans choice and freedom the racial discrimination of women continues today.