Müller: Benedetto XVI was Saint Augustine of our times

“Pope Benedict did not speak of Christ but spoke to Christ. In him there is a profound unity between theological reflection at the highest level and spirituality that entered directly into people’s hearts.” “He was well aware of his expertise, but he used it not to elevate himself above others, but to serve the good of the Church and the faith of simple people.” “About confusion? Today there is too much political, ideological thinking in the Catholic Church.” “Is the Church 200 years behind, as Cardinal Martini said? Impossible, Jesus is the fullness of all times.” Cardinal Müller, editor of Ratzinger-Benedetto XVI theological works, speaks to the Daily Compass.

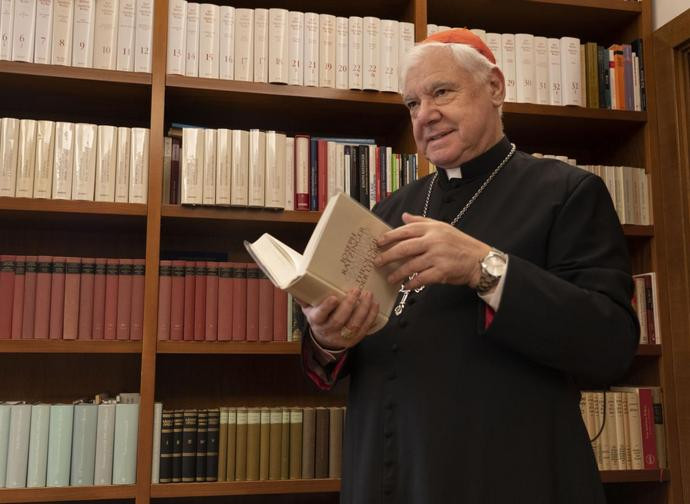

"For me Pope Benedict is almost a born-again Saint Augustine, regardless of a possible canonisation process he is already a de facto Doctor of the Church”. Cardinal Gerard Ludwig Müller ogical work of Joseph Ratzinger-Benedict XVI, as well as being one of his successors as Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. He welcomes us in his apartment near St Peter's, once habited by Cardinal Ratzinger's for 24 years, from the time he was called to Rome by St John Paul II in 1981 until April 2005, when he succeeded him as pontificate. All that remains in the apartment from that period are the stained glass windows in the small chapel, which were gifted to Cardinal Ratzinger and depict the Eucharist.

Cardinal Müller, in what way do you see St Augustine in Pope Benedict?

I believe that Pope Benedict represents for the theology of the 20th and 21st century what Augustine represented for his time; his writings are the Catholic faith explained in a way that is appropriate for contemporary people, a form of reflection far removed from the style of the theological textbook. Likewise with Augustine, it is not a matter of mere intellectual capacity, even though he was a great theologian.

What then is the 'secret'?

Like Augustine, Benedict did not deal with Christ as a subject to be developed, he did not speak of Christ but spoke to Christ. In St Augustine's Confessions, everything is a dialogue with God, man in dialogue with God, the explanation of his life. So also in Benedict there is a profound unity between theological reflection at the highest level and spirituality that entered directly into hearts, unity between intellect and love. He always said, our Catholic faith is not a theory on a subject, but it is relationship, relationship with Jesus, we participate in the Intra-Trinitarian relationship. So Benedict was able to open people's hearts. And we saw this in these days after his death and at the funeral: he remained very much alive in the hearts of the faithful, of many people. Many thought that ten years after his renunciation the world had forgotten him; instead, he is very much present in people’s memory.

In your opinion, is there a work by Ratzinger-Benedict that best expresses this unity?

He has written many books and essays, but I believe that the trilogy on Jesus of Nazareth (published when he was already pontiff, between 2007 and 2012, ed.) is the key to interpreting everything else. This book on Jesus expresses the unity of cognitive theology and affective theology, and when I say affective I do not mean sentimental, but an expression of love, of the relationship with God. This is why millions of the faithful who have not studied theology, who are not experts in philosophy, or the history of European thought; those faithful who pray every day, who go to church and have a relationship every day with Jesus, have been able to read and understand this trilogy as the intellectual, cognitive, and affective key to encountering Jesus.

You who have edited all of Ratzinger-Benedict's theological work, can you tell us what is the unifying element of his theology?

Certainly the relationship with Christ, although it must be specified that it is within a Trinitarian horizon, not the Christocentrism typical of Protestantism. And then the relationship between faith and reason. Throughout history there have always been attempts to oppose reason to faith, you just need to read and reread the controversy between Origen and Celsus, or the discussion with the Neoplatonic intellectuals. But certainly this tendency has taken root especially since the Enlightenment, the exaltation of the light of reason against the light of Revelation. As he also says in his Spiritual Testament, there was the claim that all the results of the natural sciences and historical research, i.e. the historical-critical method of interpreting the Bible, went against revealed Christian faith. False claim, as Benedict proved. He grew up and formed his conscience in times dominated by aggressive atheism, by an anti-humanism that found its application in the Nazi regime. His Catholic upbringing made him immediately aware that there was no possible reconciliation between faith and this Nazi ideology, as well as with other ideologies that deny God. When Pius XI's encyclical against Nazism, Mit brennender Sorge, came out, Joseph Ratzinger was ten years old, but the contradiction between Christianity and Nazism, as well as other atheistic ideologies, was clearly explained there. When one denies God, the consequences are clear: Jacobin terrorism, gulag terrorism, Auschwitz, the Killing Fields, Katyn, but also abortion and euthanasia. These are the effects of atheistic humanism, as Henri De Lubac called it, that we still see today: in China, in North Korea. But the same applies to Islamic countries: they say they believe in God, but in another sense....

And here we come to the famous Regensburg speech.

Exactly, it was the central point of his pontificate. Not acting with the Logos, that is, according to reason, is contrary to the nature of God. And one ends up justifying violence in the name of God, who is our creator.

You had frequent contact with Pope Benedict, even after his resignation. What struck you about him?

He was a very humble, very simple man; he was not proud nor did he pose as an important person. He did not have that arrogance typical of intellectuals who, having knowledge, consider themselves superior to others. Pope Benedict was well aware of his expertise, but he used it not to elevate himself above others, but to serve the good of the Church and the faith of simple people.

In his spiritual testament, Benedict invites all the faithful to remain firm in the faith and not to be confused. What do you think is causing confusion in the Church today?

From what I see from my experience, there is too much political, ideological thinking in the Catholic Church. I remember when Cardinal Martini - who was also an excellent exegete - shortly before his death said that the Church is 200 years behind. This is an absolutely false hermeneutic. The Church founded by Jesus Christ cannot be behind the times, Jesus is the fullness of all times. Christ is the same yesterday, today and always. St Irenaeus of Lyons, to the Gnostics who claimed to have a novelty, to be ahead, replied that if the Logos of God has revealed himself there is no other novelty. This is the point of reference. There was Christianity in the Middle Ages and there was Christianity in earlier times, but Christianity is not tied to a particular time. When I read the writings of St Augustine, St Basil, St Irenaeus, I see that it is my own faith. Styles, circumstances may change, but not the faith. One must not be confused by so many voices, the clear orientation is in Jesus Christ and the truth.

In these times we see that much confusion is also generated around the figure of the Pope.

The Magisterium serves Revelation, it is not above it, as Dei Verbum says in number 10. It is not that something is truth because the Pope says it, but the opposite: since this is the truth, the Pope must present it and explain it to the Church. That of the Pope is not a political power, neither absolute nor relative. He has the authority to teach God's people but in the name of Jesus Christ, not his own authority. The Pope cannot say that homosexual relations can be blessed, or that divorce can be accepted, or adultery justified because it is less serious than murder. The Church's teaching is clear, one cannot confuse objective evil with the weakness of persons. Conversion does not consist in relativising God's commandments.

Yet strong pushes in this very direction are coming from the German Church, and Rome's attitude is not very clear.

The documents of the Synodal Way are openly heretical, they contradict Revelation as it is expressed in the Bible and in the anthropology of Gaudium et Spes, that is, the conception of mankind created in the image and likeness of God. The unity of body and soul excludes this absolutisation of sexuality, only as a source of sexual pleasure.

But why is it that the majority of German bishops are far from Benedict's position?

An important part is played by the officials of the Central Committee of German Catholics (Zdk, the committee that represents all forms of laity in Germany and has a very important influence on the direction of the Church, ed), who put pressure on many bishops, supported also by the liberal, socialist, and communist press, obviously very happy when the Church destroys itself. But there is unfortunately also an anti-Roman complex that has existed in Germany for 500 years and has Prussian Protestantism as its reference, which considers itself intellectually superior to all the peoples of the South. Hegel wrote that the Prussian state is the culmination of the self-development of the absolute spirit, as if God had incarnated Himself in the Protestant Prussian state. These are foolish ideas but very deeply rooted. So this group claims to be the locomotive of the universal Church, as if they had invented the Church all over again. When the president of the German bishops says “we are Catholic Church but different”, what does he mean? St Irenaeus said: the faith of the Apostolic Church is the same throughout the world, Libya, Egypt, the Celts, France, Spain. The customs are different, the languages are different, but we are all united in the same faith, which is not a programme developed by a committee, but the revealed faith in Christ. It is this that unites.