Mortara case film at Cannes arouses anti-Catholic sentiment

Yesterday at Cannes was the day for Bellocchio's film (Kidnapped) on the Mortara case, the Jewish child baptised in articulo mortis and then separated from his parents. Already in the trailer, the mystification of facts is clear. Facts that Edgardo Mortara himself, who died in the odour of sanctity, effectively reconstructed in a memoir indigestible to the enemies of truth.

Yesterday, the Cannes Film Festival screened Kidnapped Marco Bellocchio's film centred on the Mortara case, the child who was separated from his Jewish family of origin in 1858 following a Christian baptism which took place because of exceptional circumstances. The film is loosely based on a book by Daniele Scalise (Il caso Mortara, Mondadori, 1996), which helped to revive the black legend against the Catholic Church. Apart from the title of the film, one can tell from the trailer the kind of mystifications that will be shown later on the big screen.

In the trailer we see an ecclesiastical messenger who goes in the middle of the night, accompanied by some guards, to the Mortara house to tell them for the first time that their son Edgardo has been baptised and that there is an order to “take him away”. The father is then seen suddenly taking the child in his arms and heading for the window, shouting: “They want to take him away from us!”. It has to be said this is a fictionalised version, but the sensational distortion of the facts - for a film that claims to refer to a true story - remains nonetheless. As will remain the mental conditioning of those who will see similar scenes, ignoring precisely the many truths withheld, to the detriment of the Catholic Church.

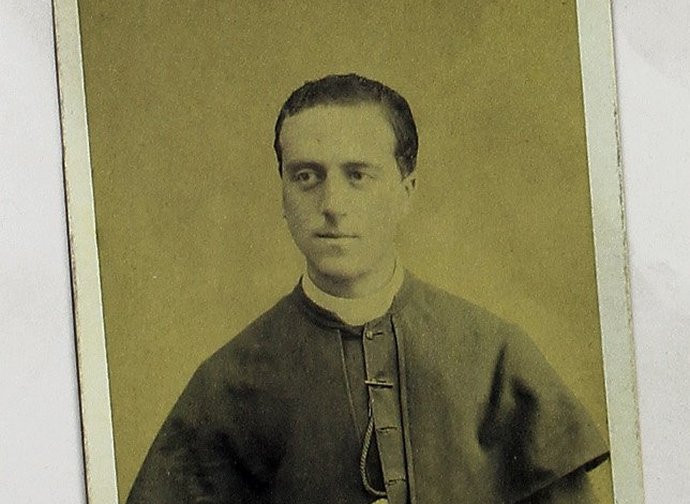

Yet, it would suffice to read the exhaustive memoir that the protagonist of the affair, Edgardo Mortara, wrote in his prime, in 1888, when he was 37 years old. A memoir written in Castilian during his apostolate in Spain and then kept in the Roman archives of the Canons Regular of the Most Holy Saviour of the Lateran, the order into which Don Pio Maria Mortara, his religious name, freely and sincerely wished to enter as soon as his age allowed him to do so. Translated into Italian, the memorial was published in full in 2005 in a book by Vittorio Messori «Io, il bambino ebreo rapito da Pio IX». Il memoriale inedito del protagonista del «caso Mortara» [«I, the Jewish child kidnapped by Pius IX». The unpublished memoir of the protagonist of the «Mortara case», Mondadori; this book was later translated into English and published by Ignatius under the title: Kidnapped by the Vatican? The Unpublished Memoirs of Edgardo Mortara], which dismantles the black legend piece by piece and gives an exemplary account of the reasons of faith. It is therefore curious that certain cultural elites continue to prefer partial reconstructions in order to propagate their ideology. So let’s examine the facts.

We are in Bologna, then one of the Papal States. Edgardo, ninth of Marianna and Salomone Mortara's 12 children, was little more than a year old when he is struck down by a terrible illness with violent fevers. The illness progresses with such symptoms that within a few days the doctors give him up for dead. Death appears imminent. It is in these circumstances that the young Anna Morisi, the Mortara family's Catholic maid, remembers what the Church teaches about baptism of necessity, i.e. in articulo mortis. Secretly, with a glass of water in her hand, she baptises the child by sprinkling him, thinking that this gesture would soon give little Edgardo access to Paradise. Only, the expected death does not come. Little by little, in fact, the child makes a full recovery. Anna panics, realising the possible consequences of her revelation. And she decides to keep silent.

About five years pass. This time, it is Edgardo's little brother, Aristide, who falls ill. He too is in mortal danger. Anna's friends beg her to baptise him, but she refuses, and finally confides what happened five years earlier with Edgardo. Meanwhile, little Aristide dies, unbaptised. On the advice of her friends, Anna reveals the incident with Edgardo to her confessor and shortly afterwards the chain of communication, with the young woman’s consent, reaches the pope. Blessed Pius IX wastes no time. He gives orders that all possible attempts at conciliation be made, to make the parents understand that the Church has a duty - as Edgardo had been extraordinarily but validly baptised - to give the child a Christian upbringing. The pope himself assured that he would keep the child in a Catholic boarding school in Bologna at his own expense, where he would remain until he came of age and where the parents could visit him at their leisure.

It must be added that in the papal territories there were at that time laws forbidding Jews to have Christian servants in their service: these laws were intended to protect the Jewish community itself, avoiding complicated situations at the outset, as had already happened under other popes. Edgardo’s parents knew, in short, what 'risk' they were running by taking a Catholic into their home.

But in spite of everything, the Mortaras, grief-stricken and angry, rejected the various attempts at conciliation that followed over time, even when they were informed by the good Father Pier Gaetano Feletti (in charge of handling the case) that the Church would be forced - with regret - to proceed with the forced kidnapping of the child in the event of further refusal. This happened, after further preparation, on 24 June 1858. The unexpected 'kidnapping' filmed by Bellocchio is therefore a historical fake.

Moreover, the kidnapping was necessary because of the danger that Edgardo would be driven to a forced apostasy and because of the heated climate that the broad faction opposed to the Church had created, to the point of threatening bloody clashes. On the pretext of wanting to defend the Jewish community, but in reality to humiliate the Church, governments, the press, Masonic lodges, and politicians from halfway around the world pounced on the case. Leading the opposition, as Don Pio Mortara himself explains, was Napoleon III, manoeuvred by the aforementioned lodges and annoyed by an ecclesiastical attitude that he considered anachronistic. He was followed closely by the Count of Cavour and others, who saw in the case of that child - as emerges from the letters of those same figures - a unique opportunity to put an end to the Church's temporal power. In fact, the Mortara case helped to accelerate the 'Roman Question' that culminated in the breach of Porta Pia. But above all, that attack was directed at the Church's spiritual mission.

What the secularists and even liberal Catholics of the time refused to accept was the meaning of the sacrament of Baptism, which was instead well known to Pius IX and would later be explained with extraordinary effectiveness by Edgardo. Despite the fact that for the first seven years of his life he had been brought up in the strictest observance of Judaism and had never heard of Jesus, Don Pio Mortara testifies, with various examples, how the invisible action of Grace was at work in him even before the kidnapping, arousing in him as a child a supernatural attraction towards churches and Christian services.

Even the docility he showed from the first hours after the kidnapping, albeit amidst some understandable signs of rebellion at being separated from his parents, is inexplicable to a merely human logic. On the journey to Rome, he had been taught the Our Father and the Hail Mary, along with the first rudiments of the Christian faith. The working of Grace in the soul of the little Mortara was such that when his parents arrived in Rome a short time later - visiting him for at least a month in the hope of bringing him home - it was the child himself who looked at that prospect with horror. And this despite the fact that he felt a great love for his parents and would continue to feel it all his life. But even then, as a seven-year-old boy, he prayed for them to accept Jesus. Edgardo was and already felt himself to be a Christian in every way, and from then on, until the end of his earthly life, at the age of 88 and a half, he would try to win souls to Christ, dying in the odour of sanctity.

All this after a life lived in profound gratitude to the men and women who had made him a son of the Church, from Anna Morisi to Pius IX. A pope who - to quote one of the many eulogies contained in Mortara's memorial - “postpones everything, forgets everything, in order to take care of the future of a poor child whom a young maid has made a child of God, a brother of Christ, an heir to eternal glory in the bosom of an Israelite family. To save the soul of this child, the great pontiff endures everything, exposes himself to everything, sacrifices everything, even puts his States at risk, before the fury, the infernal fury of the enemies of God”. A pope, therefore, who was moved by a single awareness: not even the whole world is worth a single soul.