Ireland in 20th century: cruel and harsh but the Church wasn’t to blame

Ireland in the 20th century may have been cruel and harsh, but the Church wasn’t to blame. The report on Catholic "Mother and Baby Homes" of the twentieth century largely disproves the black legend about the mistreatment and exploitation of women and children. It makes us reflect on the Church's inability to counter social norms and to create a culture of respects for all persons.

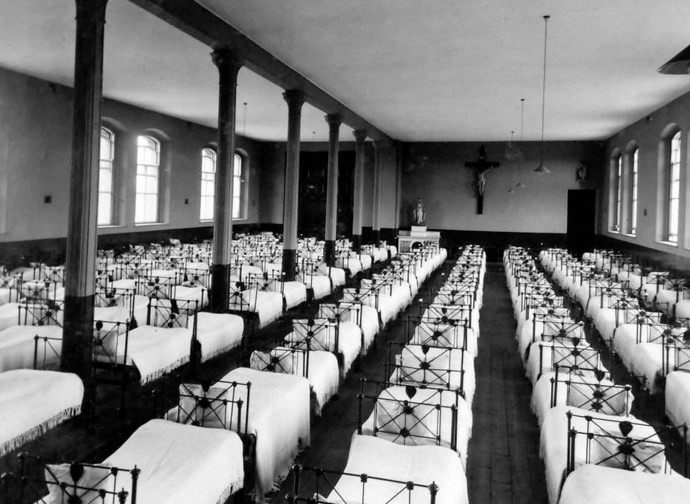

A new report on institutions which were run by the Irish Catholic Church has fired up debate around Ireland’s treatment of unmarried mothers in the 20th century. ‘The Final Report for the Commission Investigating the Mother and Baby Homes’ was released on Tuesday January 5 – it came to 2,800 pages and covered 76 years (1922-1998), studying 18 of the mother and baby homes. The homes were an institution for unmarried mothers to give birth without ‘respectable’ society knowing about it, and for the adoption of the children by new families.

The homes have been a source of ongoing controversy for the best part of 15 years, when a local historian Catherine Corless, discovered that 800 children had died in the Bon Secours Mother and Baby Home in Tuam, County Galway. The infant mortality rates in many of these homes was very high and the facilities were poor – to our modern eyes, they seem barbaric, serving a society which stigmatised the most vulnerable in society, namely poor single mothers and their children.

If you were to believe the coverage from the secular media, you would assume that the Church and Catholicism were wholly responsible for their creation. The Church is accused of subjugating the Irish people, while its emphasis on sins of the flesh and their latent misogyny is apparently represented in these homes, where the children of illicit relationships and their mothers were effectively abandoned by society and abused by the Church.

The report paints a subtler picture, however, which doesn’t easily fit this narrative. The report does not shy away from laying the blame on the Church, which must reflect on how it failed in its Christian mission. But it also points out the complicity of the state and lays much of the blame on “the fathers of their children and their own immediate families”, who meted out a harsh treatment on unmarried mothers.

The report found that “Ireland was a cold harsh environment for many, probably the majority, of its residents during the earlier half of the period under remit”. The commission found Ireland was “especially cold and harsh for women”. While the report highlights that the mistreatment of unmarried mothers “was supported by, contributed to, and condoned by, the institutions of the State and the Churches”, at the same time, the commission found that “that the institutions under investigation provided a refuge – a harsh refuge in some cases – when the families provided no refuge at all”.

One of the key undertakings of the report was placing the homes in a global and local historical context. In doing this, the report put to bed the idea that the Church was solely responsible for creating the culture which was so harsh on women. For example, the report highlights that Ireland established homes much later than Britain, and there were comparable institutions across Europe and the United States: “By 1900 mother and baby homes were found in all English-speaking countries, and similar institutions existed in Germany, the Netherlands and elsewhere.”

The report also places the conditions of the homes in the context of Ireland in the 20th century, a country that verged on being ‘third world’ in terms of poverty and infant mortality. The report found that “while living conditions in the mother and baby homes were basic, there is no indication that they were inadequate by the standards of the time, except in Kilrush and Tuam”. The report contrasts the mother and baby homes with the county homes, which were run and staffed by the Irish government: “Conditions in the county homes were much worse than in any mother and baby home, with the exceptions of Kilrush and Tuam. In the mid-1920s most had no sanitation, perhaps no running water; heating, where available was by an open fire; food was cooked, badly, often in a different building, so it was cold and even more unpalatable when it reached the women.”

Finally, the report puts to bed a number of rumours about the behaviour of the nuns who ran the institutions. Nuns did not make money from the homes; they did not work women to the bone; they did not systematically abuse the women and children. Even with regard to infant mortality, which was high even by the standards of the time, it shows how the infant mortality rates were not the result of deliberate neglect, but of a combination of poverty, overcrowding and poor sanitation.

The reaction of those who expected the report to pillory the Church and, to a lesser extent, the state were confounded by the fact that blame was laid on society entirely. The response of a number of commentators and politicians has been that the report is a deliberate effort to shift blame from the Church and State. However, they cannot escape the implication of the report that our grandparents and great-grandparents were as much to blame in shaping the culture as the institutions which supported it.

However, it is important to reflect on and acknowledge the Church’s role in condoning and perpetuating a culture that stigmatised women in this way. The most senior archbishop in Ireland, the Archbishop of Armagh Dr Eamon Martin, released a statement in which he “apologised unreservedly” for the Church’s maltreatment of unmarried women and their children. Speaking of his deep sadness at reading the report, he said "we are shamed, really, to realise and think of the number of vulnerable women and their unborn children and then their infants who were stigmatised and shamed and excluded from their homes and families”.

What Archbishop Eamon Martin reflected was that the Church had not lived up to its own standards. He said the Church must continue to acknowledge before God and others its part “in sustaining what the Report describes as a ‘harsh … cold and uncaring atmosphere’”. The mother and baby homes are a stain on Irish society, one to which all its various members and bodies contributed. The Irish Church, as the pre-eminent social institution of the time must bear its fair share of the blame – had it been more counter-cultural, had it preached and practiced the full extent of the Gospel, then we could look back on our actions with a sense we did all we could. But that isn’t so, and we must reflect on how it is we can repair the damage and move forward in the light of Christ.

* The Irish Catholic