Fratelli tutti, a vision in contrast with John Paul II

We’d like to compare the vision of "Fratelli tutti" with the homily delivered by St. John Paul II at the beginning of his pontificate, when he cried out “Open wide the doors to Christ”. These are two completely different visions, and Pope Francis’ encyclical marks a break in continuity with the social encyclicals prior to it. What is the simple person in the pew supposed to think and do?

In a nutshell: our selfsame nature lets us know we are all brothers and are called to forge universal fraternity; this is why we have to overcome our individual forms of egoism, and our self-isolation in order to be able to create an open society based on inclusion, love for each person, and enhancement of the poor and the last of the last; necessary in sundry fields in order to help all nations to this end is a “global governance”, an international authority able to get individual countries moving in the right direction and impose sanctions on them when they close themselves off; all religions also have a vocation to universal fraternity and must help pursue that end; an example of this is the document on human fraternity signed in February 2019 by Pope Francis and the Great Imam Ahmad Al-Tayyeb ( The Abu Dhabi Declaration) which is the primary source of inspiration for this encyclical.

This in summary is the basic thought underlying “Fratelli tutti” the encyclical of Pope Francis rendered public on Sunday, the 4th of October.

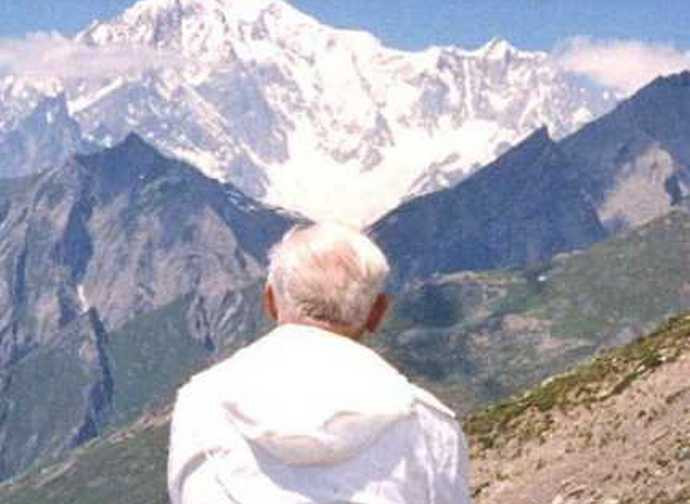

Coming to mind is the famous excerpt from the homily delivered at the beginning of St. John Paul’s pontificate (22 October 1978), which is also the programme and the synthesis of his pontificate

“Do not be afraid. Open wide the doors for Christ. To his saving power open the boundaries of States, economic and political systems, the vast fields of culture, civilisation and development. Do not be afraid. Christ knows "what is in man". He alone knows “

A brief homily resolutely announcing the power of Christ over the world and the Church’s evangelising mission as defined by Vatican Council II. As John Paul II said, there is only one response to the uncertainty, the despair of both individuals and entire peoples, and that is Jesus Christ. “We ask you therefore, we beg you with humility and trust, let Christ speak to man. He alone has words of life, yes, of eternal life.

Therefore, the formulation of the encyclical “Fratelli tutti” could not help but bring to mind those words of John Paul II we just heard, and this because they project two radically different and even opposing visions. This is something that necessities some questions.

In the mind of Pope Francis, the ultimate end of each person, with Christians in the forefront, is to construct universal fraternity: human reason alone suffices to conceive it and recognise the instruments needed to bring it about. And all religions without distinction must be of help in this, because each and every one of them is called to pursue this end.

For St. John Paul II, however, Christ alone is the comprehensive response to the questions of both man and peoples at large. The entire world is under His power. He alone has “words of eternal life”.

The vision Pope Francis depicts in “Fratelli tutti” is not a version of that certainty voiced by St. John Paul II, and is clearly something else. Instead, it seems to be on the same wave length as the thinking that inspired “Our Global Neighborood” , the Report of the UN Commission on Global Governance. Published in 1995, this Report outlines a global ethics for a fraternal world, a world at peace. The inspiration and the constituent values of this global ethics may be clearly assimilated to the ones set forth in “Fratelli tutti”. What we have is a manifest with a socialist and utopian bent that claims to encompass each “country, race, religion, culture, language, and style of life”. Religions, which may well concur on these common values, are obviously necessary in this plan because they are able to exercise control over a very high percentage of the world’s population.

Quite natural, therefore, is the first question: is this perspective compatible with the Catholic vision? If we side with John Paul II, who evokes Vatican Council II, not at all. Peace, fraternity is possible – says St. John Paul II – if the boundaries of States open to the power of Christ, not immigrants; if economic and political systems, culture and every aspect of society open to the power of Christ. The Church exists only to live and announce this.

It doesn’t take that much reasoning to realise that the encyclical “Fratelli tutti” is a reversal of this vision. It clearly isn’t a matter of two diverse sensations, or a stressing of different aspects of one and the same vision driven by living during two different times of history. Evident when reading the Rerum Novarum of Leo XIII and the Centesimus Annus of John Paul II are the one hundred years separating these two encyclicals, but equally clear is the seamless nature of the vision shared by the two pontiffs.

Here we are faced with something that interrupts this continuity, and it cannot be by chance that approximately two-thirds of this encyclical’s references are citations from Pope Francis’ previous speeches, messages, and encyclicals

At this point, a further question becomes inevitable: what must we in the pew think and do if we don’t want to shut our eyes in the face of this evident lack of continuity?