Francesca Cabrini, an intransigent saint

Foundress of the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, on the advice of Leo XIII she left for America to evangelise and help Italian emigrants. She set up nurseries, schools, boarding schools for students, orphanages, rest homes, and hospitals. She gave extraordinary value to female religiosity and practised charity in a thousand ways. She never compromised with evil.

Granada, Minnesota, USA, 1895. The man is sitting on a hard wooden chair, his head bowed. The nun, sitting on the other side of the desk, is giving him a lecture such as he hasn't heard since he was a boy. The nun, Mother Superior of the posh Catholic school where his daughters study, is sterner than his parents ever were when they scolded him. She isn't even scolding him: she speaks in a calm, almost velvety voice, while telling him terrible things. She reproaches him for not having obeyed God's law by breaking the sacred marriage vow of fidelity. He, who repeatedly cheated on his wife, is also the father of an illegitimate daughter, conceived with a black prostitute, the daughter of slaves. He wanted her mother to "donate" her to the monastery.

But the nun does not compromise: she will take the child in, but he must officially recognise her, give her his name and a dowry. The man is in a quandary: while he spasmodically clutches the hat on his lap, he explains to the nun that he is married and has four legitimate children. But the nun will have nothing of this. She threatens to expel his two "legitimate" daughters from the school she runs. Finally, the man agrees. They agree on everything: legal recognition, the baptism of the child, the notarial deed awarding the dowry. Once these acts are completed, the school will take charge of the girl's education, and he will have to pay the (very high) fees. The nun smiles and he cannot help thinking that it is a pity that such a charming woman is a nun. She gets up to dismiss him, while congratulating him on his decision (as if he had a choice, he thinks) and telling him that he has acted like a good Christian. He is a rich Italian-American importer, in his fifties, elegant and handsome, used to being in charge. But not with her. He has known her for years and she has always intimidated him.

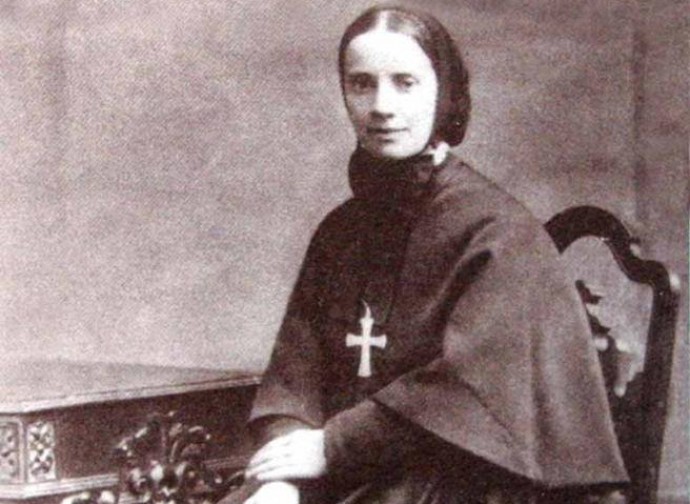

She is Francesca Saverio Cabrini, an Italian nun, born in 1850, the last of thirteen children. She is the founder of a religious congregation that has the characteristic of being completely autonomous, that is, not parallel to a male order: the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart of Jesus.

She is Francesca Saverio Cabrini, an Italian nun, born in 1850, the last of thirteen children. She is the founder of a religious congregation that has the characteristic of being completely autonomous, that is, not parallel to a male order: the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart of Jesus.

With a strong vocation felt from an early age, Francesca took her vows at the age of 24. Then her strong-willed character and thirst for justice led her to surpass herself: she not only founded a religious congregation, but also moved, at the suggestion of Pope Leo XIII, to the Americas, with the idea of evangelising those distant lands. Here, she helped the many Italian immigrants in particular and immediately realised that what they needed were schools. Especially for the girls, who were rather neglected. And she knew something about this: even as a child she had suffered inequality with her male siblings. And a desire was born in her to do justice, in the good sense of the word.

And so, after founding the Missionaries and arriving in the Americas, she learned English and Spanish and, on the back of a mule, arrived in the most inaccessible places in South America to evangelise entire tribes that had never come into contact with whites. Being a missionary was a male prerogative, but Cabrini made the women's society she founded very active in missionary work. Her charitable initiatives soon developed into economically self-sufficient works of assistance, through the parallel provision of paid services. The Missionaries provided immigrants with language courses, bureaucratic assistance, correspondence with their families of origin, reaching out to the most marginalised either logistically or because they were ill or housebound.

She set up schools for girls of all social classes - the rich paid for the poor - admitting girls of any religion to study there: for her it was an opportunity to transmit the Word of God to them and make them fall in love with Jesus. She forced men to recognise illegitimate children, appealing to their sense of honour, as we saw in the episode described earlier. On feast days, she opened the Congregation’s institutions and invited the poor to eat the "Sunday dish" par excellence of Italian immigrants, spaghetti and meatballs. At Christmas time, she would send a cloth bag containing a piece of Parmesan cheese, a bottle of wine, a panettone, and a salami from Calabria to the homes of the less well-off, gifts that she obtained from the many importers of Italian products, who were already prosperous at the beginning of the 20th century.

Her schools were prestigious because of the quality of teaching and the variety of subjects that prepared girls for the many different aspects of life. She was convinced that a woman should work, if only doing charity work, even if she was 'well married', because work gave her self-confidence. She passed this idea on to her disciples and stood up to their parents who sometimes criticised her for these 'liberal ideas'. It became a (good) fashion for rich families to have their daughters study in the College of the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart of Jesus opened by Cabrini in Granada. But there were also other institutes she created: kindergartens, schools, boarding schools for students, orphanages, rest homes for lay and religious women, hospitals in New York and Chicago, operating in seven countries with 80 institutes. In 1909 she became a US citizen. Cabrini was also a great traveller: she crossed the Atlantic 28 times. She also travelled to the Andes from Panama.

She was able to enhance women's religiosity in an extraordinary way, far beyond the times in which she lived, responding to issues that are still relevant today because of the migration. For her initiatives she is considered one of the references of modern social service. She saw in the principles of American democracy a means of integration and social advancement for Italian immigrants. She promoted the emancipation of women's initiative in a thousand ways and lived her devotion to the Sacred Heart by interpreting the concept of reparation for the "offences done to Jesus" as a reason for commitment to charitable works.

She died in Chicago on 22nd December 1917 and on the day of her death her body was moved to Mother Cabrini High School in New York. In 1938 she was proclaimed Blessed, in 1946 Saint (the first US citizen), in 1950 Patroness of Emigrants. Her liturgical feast day is 22 December. Today her body is in the Saint Cabrini Shrine in New York. St Frances Xavier Cabrini is remembered in various ways. Here are some of them. In Sant'Angelo Lodigiano, where she was born, there is a bronze statue of her by the sculptor Enrico Manfrini (1987). In November 2010, Milan Central station was named after her. In 2021, a statue of her was erected in Battery Park in New York, created by the artists Giancarlo Biagi and Jill Burkee.

She died in Chicago on 22nd December 1917 and on the day of her death her body was moved to Mother Cabrini High School in New York. In 1938 she was proclaimed Blessed, in 1946 Saint (the first US citizen), in 1950 Patroness of Emigrants. Her liturgical feast day is 22 December. Today her body is in the Saint Cabrini Shrine in New York. St Frances Xavier Cabrini is remembered in various ways. Here are some of them. In Sant'Angelo Lodigiano, where she was born, there is a bronze statue of her by the sculptor Enrico Manfrini (1987). In November 2010, Milan Central station was named after her. In 2021, a statue of her was erected in Battery Park in New York, created by the artists Giancarlo Biagi and Jill Burkee.

St Frances' life is a guide for all of us: no matter what condition, latitude, or family we are born into, if we embrace God we can rise above our condition and dedicate our lives to doing good. To honour Him.