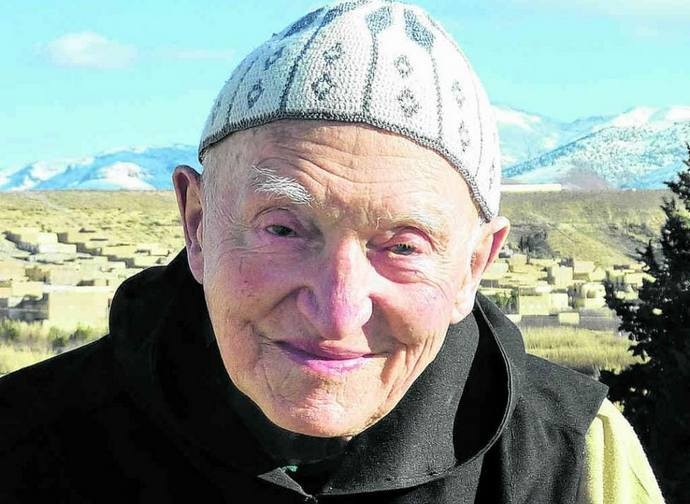

Father Jean Pierre, man of peace and prophecy

The death and funeral in Morocco of the 97-year-old Trappist monk who escaped the massacre in Tibhirine (Algeria) in 1996 showed how friendship can be born between Christians and Muslims when faith is lived in daily fidelity to the Gospel, without compromise, even at the cost of one's life. The embrace of Christians and Muslims around his tomb was the miracle of a friendship possible when the sincere search for God inhabits the human heart.

Father Jean Pierre Schumacheur now rests, buried in the bare earth as the Trappist tradition dictates, in the cemetery of the Notre Dame de l'Atlas monastery in Midelt, Morocco, alongside seven Franciscan Missionary Sisters of Mary who dedicated their entire lives to the Maghreb people. He died on Sunday 21 November, while the community was celebrating the Eucharist, with the nurse-monk by his bedside in prayer. Fr Jean Pierre is the first Trappist to be buried in this cemetery.

And to take care of his burial, immediately after the Requiem mass presided over by the Archbishop of Rabat, Cardinal Cristobal Lopez, in the late morning of 23 November, were his Muslim friends, who treated him like a father, already venerating him as a saint.

And to take care of his burial, immediately after the Requiem mass presided over by the Archbishop of Rabat, Cardinal Cristobal Lopez, in the late morning of 23 November, were his Muslim friends, who treated him like a father, already venerating him as a saint.

What did this humble Trappist do that was so extraordinary, having escaped the 1996 massacre in Tibhirine, Algeria, when seven monks, declared blessed in 2008, were martyred? From the many messages that continue to arrive from all over the world, it is clear that the life of this 97-year-old priest was a testimony of peace and a “prophecy of the future”. This is how I would define his death and the burial rites. A 'man of peace', this is what is written and said about him by all those around the world who comment on his death in the Notre Dame d'Atlas monastery, a solitary place of Christian presence in the middle of a territory inhabited by Berbers, Islamised by the occupation of the Arabs

Since September, I too have been living in the monastery, having taken over for the celebration of the Eucharist from Prior Fr Jean Pierre Flachaire who is in France for medical treatment. This gave me the opportunity to experience the atmosphere of care with which the five monks, plus a hermit, surrounded their elderly brother, whose health was becoming increasingly fragile but whose temperament was that of a leader on the battlefield until the very end.

His apostolate was dialogue by correspondence: he received and always replied personally to the thousands of letters from friends and acquaintances with whom he maintained constant spiritual contact. He told me one day, showing me a parcel of letters, "I have been in regular correspondence with these people for 17 years, even though I do not know them and have never met them. My mission is to listen, pray, and console. But now I can't do it anymore”.

It was true. Reluctantly, he had had to come to terms with it because he couldn't even write anymore, so his one commitment became prayer. He was at my side in the choir and I often caught him in the darkness of the chapel in silent contemplation. He was gradually losing his strength, the fatigue and weakness of age was palpable, but from his face transpired the peace within him that he communicated to everyone. Yes, this was his charism: to live in peace and to transmit it to everyone he met.

It was true. Reluctantly, he had had to come to terms with it because he couldn't even write anymore, so his one commitment became prayer. He was at my side in the choir and I often caught him in the darkness of the chapel in silent contemplation. He was gradually losing his strength, the fatigue and weakness of age was palpable, but from his face transpired the peace within him that he communicated to everyone. Yes, this was his charism: to live in peace and to transmit it to everyone he met.

His death, like his life, is a witness to peace and his funeral represents a "prophecy of the future" because it appears to be the logical conclusion of a difficult but fruitful path of evangelical witness in a Muslim context, first in Algeria and then in Morocco since 2000.

Something solid and lasting cannot be built without the commitment of daily fidelity to one's ideal, even at the cost of one's life.

When in the 1960s Fr Jean Pierre entered the monastery of Tibhirine, Algeria, the intention was clear and certainly courageous: to be monks among the Algerians, to bear witness to the Gospel as prayerful people inserted among the Muslim people, a people that prays.

A mission not easy to understand and particularly to accomplish. Alongside the cordial sympathy of the local people, there have been risks and threats from Islamic extremists. The first abduction attempt took place on the evening of 24 December 1993, just as they were preparing for the Christmas Vigil. The attempt was averted because the Prior told the leader of the commandos that this was a sacred night for Christians and the kidnappers released the monks, but promised to return.

The community had chosen to stay together despite the risks and uncertainties of the time. And together they lived through the drama of the abduction and killing, which took place between the night of 26-27 March and 30 May 1996 when only the heads of the seven monks were recovered. He often wondered why he had been spared martyrdom and concluded by saying that it was so that he could bear witness to the spirit of the Community of Tibhirine and continue its mission. Forced to move in 1997 for security reasons, Fr Jean Pierre joined the Trappist community in Morocco, first in Fes and then in 2000 in Midelt, where he left a tangible sign of his passage and above all of his death, which enabled many to discover him or to get to know him better.

The community had chosen to stay together despite the risks and uncertainties of the time. And together they lived through the drama of the abduction and killing, which took place between the night of 26-27 March and 30 May 1996 when only the heads of the seven monks were recovered. He often wondered why he had been spared martyrdom and concluded by saying that it was so that he could bear witness to the spirit of the Community of Tibhirine and continue its mission. Forced to move in 1997 for security reasons, Fr Jean Pierre joined the Trappist community in Morocco, first in Fes and then in 2000 in Midelt, where he left a tangible sign of his passage and above all of his death, which enabled many to discover him or to get to know him better.

In fact, the embrace of Christians and Muslims around his tomb will remain in the minds of all those present as a 'prophecy of the future'; a single family in prayer, the miracle of friendship possible when the sincere search for God inhabits the human heart. Professor Faouzi Skali, a well-known author of texts on Sufi spirituality and a man strongly committed to spiritual dialogue between the two religions, as well as being a long-standing friend of the monks and Fr Jean Pierre in particular, spoke about friendship and dialogue.

After giving his testimony, he asked the Muslims present to pray the 'Fatiha', it was an amazing sight to witness and hear. Someone rightly said that for a few minutes, the time of the prayer, the dream of the deceased seemed to come true: brothers seeking God in different ways and invoking Him with different styles but with the same heart.

What spiritual testament does Fr Jean Pierre leave behind? In these years when the confrontation with Islam has raised the question of whether it is possible to be Christian in a Muslim country, his example adds to the precious legacy of the martyrs of Tibhirine. Their example, and above all their testimony, which follows in the footsteps of Charles de Foucauld (who will be proclaimed a saint in May next year) and other precursors of this dialogue, proves that it is possible to seek a way of encounter.

However, it is not a question of cultivating theological dialogue because it would be impossible to reconcile the two different visions of God and religion. However, it is always possible for debate to become an embrace and for it to help people become friends in mutual respect, a spiritual friendship between people in search of God and a daily commitment to break down prejudices to build a fraternity made up of small gestures of respect and cooperation. This is the mark of the brotherhood that has been established between the monks and the Muslim community surrounding the monastery.

But for dialogue to take place in truth, it is indispensable, as the monks show by their presence, to live in the Church, faithful to the Gospel without compromise, and willing to give their lives so that Love may triumph. And so, these monks become signs of love and hope, "praying among praying people", silently making Jesus Christ present among a population that knows Him but does not recognise Him as God. A presence that is a sign of fidelity to the Gospel, to the Church, and to the Muslim population, a simple way of seeking and building Islamic-Christian dialogue in daily life, the dialogue of life.

The problem, the most worrying difficulty for dialogue is instead the weakening of faith in those communities that, for a false ecumenical spirit or useless do-goodism, renounce their Christian identity.

* Bishop emeritus of Ascoli Piceno (Italy)