Evangelium vitae, 30 years later there is nothing to celebrate

Thirty years ago, on 25 March, John Paul II published his encyclical Evangelium vitae 'on the value and inviolability of human life'. Today there is nothing to celebrate: morality is subject to compromise and dialogue, there is little is left of the 'people for life'.

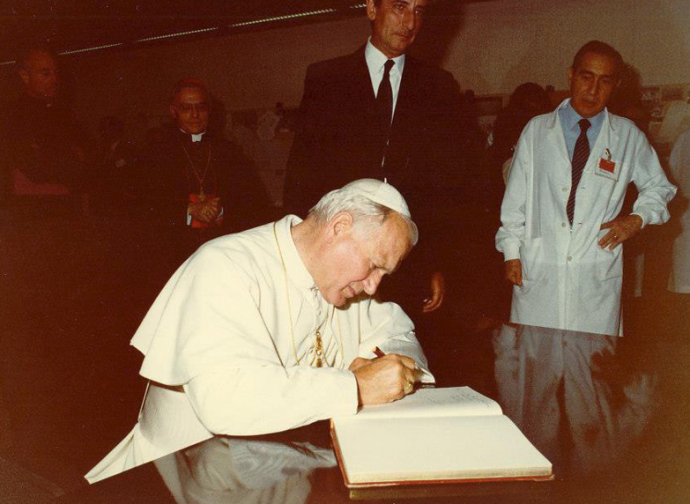

Thirty years ago, on 25 March, John Paul II published his encyclical Evangelium Vitae 'on the value and inviolability of human life'. The subject was the legalisation of abortion, but the encyclical didn't just deal with bioethics; it extended its teachings to morality, law and politics, creating a complete picture of a 'culture of life' that was to inspire a 'politics for life'. Evangelium vitae was closely linked to Veritatis splendor on morality and Fides et ratio on the relationship between faith and reason. Together, these three encyclicals of John Paul II constituted a doctrinal and orientational summa for the practice of Catholics and all people of good will in politics. The papal magisterium thus shone with clarity, depth and coherence; it did not chase after the existential phenomena of the moment, it did not let others dictate what it had to say, it was not afraid that the truths it taught might be divisive. It was only concerned to speak the truth that would set us free.

The relationship with the other two encyclicals is fundamental. If, as Veritatis splendor said, there is no moral good that can be known by reason and taught by revelation, and if there are no acts that are always evil regardless of intention and circumstances, as is the case with abortion, then the will of the individual becomes unquestionable. If, as Fides et ratio maintains, reason is incapable of recognising the natural and definitive order of being, which faith in revelation considers to have been created by a provident God and to be its ultimate end, then freedom would be a useless and harmful faculty. Today it is not possible to recover the teaching of Evangelium vitae without re-examining the entire triad of these encyclicals. In fact, all the wounds inflicted on the others are the cause of the neglect on this one on life.

Paragraph 20 is the heart of Evangelium vitae. It would be enough to reread it to get the whole picture. Society, it says, is not a collection of individuals placed side by side, but a community ordered and united by the pursuit of its natural ends. In a society seen as the sum of individuals, everything is conventionally agreed and negotiable; in a society seen as a community organised according to its natural and supernatural ends, on the other hand, the fundamental bonds are not available to the citizens, and the ends are not chosen but given to us by our very nature. In the first case, morality is considered to be satisfied by compromise, the law to be denied by a parliamentary vote; democracy, "contradicting its own principles, effectively moves towards a form of totalitarianism", while the State is transformed into a tyrant. As we can see, the picture is organic: from the natural order we move to morality, then to law, and finally to politics.

The teaching of Evangelium Vitae on the foundations of a culture of life does not stop at this natural level, but goes deeper in its critique of secularism, which involves the eclipse of God. There is no place for a humanism without God, because "when the sense of God is lost, the sense of mank is also threatened and poisoned". The process is circular. The loss of the sense of the true and only God also obscures the vision of the natural moral law, which is incapable of standing on its own, and the systematic violation of the latter, in the fight against the dignity of life in its infancy, entails the loss of the sense of God. The question of life in the face of the powerful attacks of inhuman laws, promoted by worldly powers well equipped for this purpose, requires people that proclaim life by proclaiming the Gospel. It will never be possible, then, to betray the truth about human life by putting forward ideas contrary to the Gospel and collaborating with them through personal and political action.

Thirty years on, we wonder what has become of these "people for life" and how much of the teachings of the Evangelium vitae they still have in their consciousness. At the moment, the link between the three encyclicals mentioned seems to have weakened. Instead of speaking of a society united by its natural ends, we prefer to speak of an existential situation of being in the same boat, which would make us all brothers. In this way, conflicts over life disappear and are replaced by dialogue and mutual support. In ethics, absolute negative norms are replaced by processes of discernment which, by their very nature, exclude the irrevocable condemnation of behaviour. Even the plans of law and politics no longer seem to require consistency with natural and divine moral law, believing that such attitudes are contrary to charity, understood as acceptance of all who are different because they are different. Overall, the picture has become fragmented, case by case, and has lost depth, while other dramas of life have been added to the drama of abortion, which has not diminished. In particular, the relationship between social and political commitment to life and evangelisation seems to have been greatly weakened.

Thirty years later there is nothing to celebrate.