Cop29, another flop: talks about money not climate

Three hundred billion dollars a year by 2035 from industrialised countries to developing countries is the only agreement that came out of the climate conference (contested by the poorest countries). The climate emergency is a pretext for financial speculation.

The step-by-step energy transition is a flop, and the money is not there. This is the sad reality that explains the umpteenth failure of the annual Conference of the Parties (COP, i.e. the countries that have ratified the Framework Convention on Climate Change), now in its 29th edition, which has just ended in Baku (Azerbaijan), two days later than planned, precisely because of the difficulty in finding any concord. In the end an agreement was reached on the amount that has to be transferred from developed countries to developing countries: 300 billion dollars a year by 2035, i.e. three times more than previously agreed.

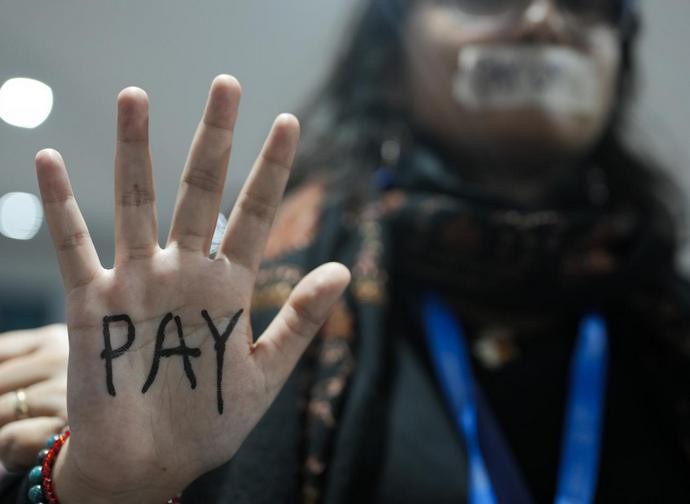

But it is an agreement that saves face, not substance. First of all, because the USD 300 billion still has to be found: the developed countries are essentially taking the lead in this search for funds ‘from a wide variety of sources, public and private, bilateral and multilateral, including alternative sources’. But above all, the figure is well below what the poorest countries considered fair and requested: on the eve of the Cop29, there was talk of figures ranging from one thousand billion a year to several thousand billion; and after weeks of tough negotiations, the G77+China group (which includes most of the countries of Latin America, Africa and Asia) had come to indicate 500 billion dollars as the insurmountable line below which it was not possible to fall.

In the end, however, they had to settle for an agreement on USD 300 billion, which was, however, fiercely contested by the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS in the English acronym) and the Least Developed Countries (LDCs), whose delegations even left the negotiating room at one point. And India's representative strongly criticised the ‘appallingly low’ figure, which makes ‘climate action necessary for our country's survival’ impossible.

Precisely this last stance gives an idea of a short circuit that has been created in the world by taking CO2 emissions as a fundamental criterion even for financial relations. In the negotiations, in fact, one of the requests of the developed countries was to include the countries that are part of the enlarged BRICS group among the subjects that must feed the ‘compensation’ fund in favour of poor countries; China, India, Brazil and the others instead conceive of themselves as developing countries, damaged, and therefore recipients of the funds. The fact is that China is the country that emits the most CO2, about 31% of the total; and right after the United States (13.5%) is India (7.3%) in third place. And India is the one that is registering the fastest increase in emissions: doubled over the last 15 years, it promises - hand in hand with development and the need for energy - to multiply them still further in the coming years; suffice it to say that India's main source of electricity is coal (70% of the electricity mix), with a production capacity that has quadrupled in the last five years, which it plans to double even further between now and 2032.

In other words, the situation that has been created is so paradoxical that the European Union and the United States should also finance countries like China and India, which alone account for almost 40% of global emissions and which for their development make extensive use of energy sources that have become taboo for us. And just when the strict ‘green’ targets embraced by the European Union - and only by the European Union - are putting both industry and agriculture in crisis. The case of the crisis in the automobile industry is there to prove it. The European Union, which, moreover, risks being left alone since with the Trump presidency, the United States has already announced that it is pulling out of the Paris Agreements (2015) of which this financial plan is also an offspring.

It is increasingly clear that the whole business of climate policy is being reduced to a financial mega-transaction: transfer and speculation. On the basis of the existence of an alleged climate emergency, for which the rich countries would be responsible to the detriment of the poor ones, compensation plans and policies are being put in place that envisage the transfer of huge sums of money from industrialised countries to developing ones, as in fact envisaged in the Baku agreement. On the other hand, the carbon market is being extended globally, under the auspices of the UN, which is already functioning in the European Union (provided for in the Paris agreements, agreement was reached at Cop29 on the standards of this financial market).

It is an artificial construction that is based on scientific theses that have yet to be proven - that climate change is caused by human activities that must necessarily have catastrophic outcomes - and on political choices that are strongly flawed by the ideology of Third Worldism: the poor are poor because of the rich who exploit them. Not only is the basis of this construction false, but its outcome far from favouring the development of poor countries will be to destroy the economy of developed countries.

Catastrophes will not be caused by the climate but by climate politics.

Valencia floods: problem is anthropological change not climate change

The tragedy of Valencia, where floods are recurrent, suggests how dangerous the ideology is that blames mankind for climate change and forces sound land management programs to be neglected in favour of green policies which are as expensive as they are useless.

"Code red” UN climate alarm denied by facts

The IPCC's Sixth Report, published yesterday, is sounding climate emergency alarms with its usual catastrophic predictions, unless political and economic measures are not immediately taken. However, current data refute claims on the continuous rise in global temperatures. Meanwhile it is useful to remember that in 1989 the UN launched an alarm in which governments were given just ten years to reverse the trend. Thirty years later, those catastrophes have never come true.