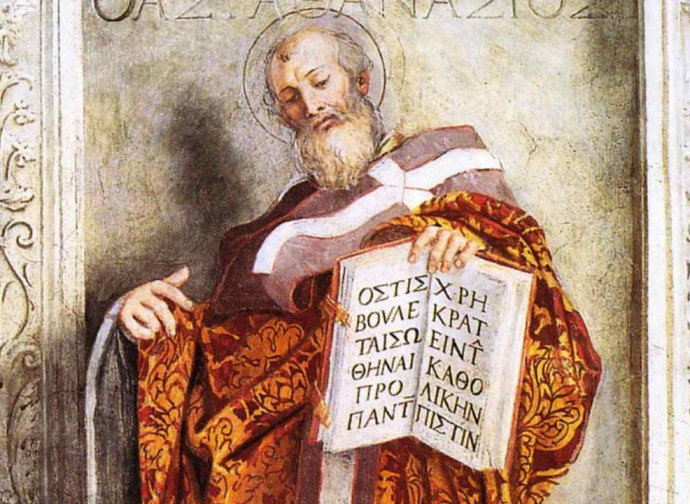

Church crisis favours false St Athanasius pretenders

Today's ecclesial crisis resembles, in some ways, that caused by the Arian heresy. But the parallel between St Athanasius and some of today's schismatic prelates does not hold up: the holy bishop of Alexandria, exiled several times, defended the faith and at the same time remained obedient to Rome.

Is what we are experiencing the worst crisis in the history of the Church? Or have there been or will there be worse ones? It is difficult to give an answer to this question as far as the past is concerned, because our more or less historical ignorance, on the one hand, and the simple fact that each one of us can only live and perceive from our direct experience, on the other hand, make it difficult to compare different historical periods. Realistically, each situation is worse than another in some respects, and better in others. As for the future, that is in the hands of God's omniscience and mercy.

Currently, it is believed that the current crisis, of all those that have occurred in the history of the Church, finds its twin, perhaps heterozygous, in the Aryan crisis. This parallel, which has its reasons, at least in terms of the vastness of the problem, has led and is leading many to find ‘new Athanasius’ in bishops and presbyters who have placed themselves in a position of rupture with the Catholic Church. Indeed, even St Athanasius, it is claimed, had been exiled five times because of his strenuous and unyielding resistance to Arianism. Not only that, but he had also been unjustly excommunicated by Pope Liberius, although the latter had acted under heavy duress while in exile because of his opposition to Arianism (for the story of Liberius, see here).

The context of the Arian crisis is indeed as close as one can get to today's situation; St Gregory Nazianzen's description of it in his extraordinary Oration XXI (no. 24), dedicated to Athanasius, appears eloquent: ‘Indeed “shepherds have become senseless”, as Scripture says, and “many shepherds have destroyed my vineyard, disfiguring the desirable part”: I am referring to the Church of God, brought together by many labours and sacrifices both before and after Christ, and also by the great sufferings that God has endured for us. For, except for a very few - and these were those who were left aside because they were unimportant or those who endured because of their valour and were to be left as seed and root for Israel to flourish again and come back to life with the infusion of the Spirit - all adapted themselves to the circumstance, differing from one another only in that some before, others after, had this fate. Moreover, some were the first combatants and leaders of ungodliness, others, on the other hand, took sides in the successive ranks, either because they were shaken by fear or because they were enslaved by necessity or because they were allured by flattery or, and this is the best case, because they were deceived as a consequence of their ignorance, assuming that this is sufficient to exonerate those who had been entrusted with the task of leading the people”.

The landscape was bleak then, as it is now. But the similarities between St Athanasius and the more recent episcopal or presbyteral figures who have decided to ‘set themselves up on their own’, end here, while radical dissimilarities arise that do not allow today's schisms to be justified by the example of the Holy Doctor. And not only for the fact that none of the ‘dissidents’ had to endure exile, precariousness, mistreatment, or slanderous accusations of deeds never done, such as that of having killed a person, all of which became daily bread for Athanasius.

Let us start with a background. Because of these false accusations, Athanasius was deposed from the See of Alexandria by the Eusebian bishops (followers of Eusebius of Nicomedia), who notified the Pope, Julius I, of the decision. The Pope made the accusations and the measure against him known to Athanasius so that the bishop of Alexandria could explain himself. In the end, he decided to summon both parties to Rome so that a fair judgement could be made. Athanasius came to Rome in the company of other bishops deposed by the Eusebians, including Paul of Constantinople and Marcellus of Ancyra. The pope not only acquitted Athanasius on the grounds of inconsistent evidence, but also reprimanded the Eusebians for deposing bishops without involving the bishop of Rome. Socrates Scholasticus, in his History of the Church (2. 17), explains that the Eusebians had violated the fundamental principle that no Church can make decisions contrary to the judgement of the bishop of Rome, by virtue of his primacy of jurisdiction, as would later be expressly recognised at the Council of Sardica (343-344). It should be noted that the Pope did not at that juncture enter into the merits of the doctrinal question, i.e. whether Athanasius' doctrinal position or that of the Eusebians was right, but claimed the primacy of Peter's successors: “Are you ignorant of the fact that custom required that we should first write to us and then that a just decision should pass from this place?” (Apology against the Arians, 1. 35). Thus, Athanasius was ‘saved’ by the Petrine primacy: the pope enjoyed (and enjoys) the right to have the last word on the appointment or deposition of a bishop, as the foundation and guarantor of the unity of the Church.

With Pope Liberius, this primacy turned against Athanasius, who, as is known, was excommunicated by him. There is no doubt about the injustice of this excommunication, which, by the way, was not taken freely by Liberius, as Athanasius himself had occasion to emphasise in his Apologia contra Arianos (cf. VI, 89). But - and this is the point - the Doctor of the Church did not for this reason question the legitimacy of Liberius' authority, nor did he continue to perform his episcopal ministry once deposed by the Pope, and even less did he confer sacred orders during this period. On the contrary, he accepted exile and deposition, without sharing their reasons, and even less bending to espouse the Arian position. And yet, while he held firm to the doctrine of the faith - he never claimed that Liberius had done the right thing in excommunicating him and signing the pro-Arian compromissory formula - he submitted to the unjust sentence, without creating a parallel church, by virtue of a state of necessity that certainly existed. Athanasius by his word confessed and defended the consubstantiality of the Son to the Father, while by his conduct he professed and upheld the primacy of Peter, in the one Church of Jesus Christ. And so, in a holy manner, he did not lose faith, nor was he overcome by cowardice or human calculations, but at the same time he did not stretch out his hand against the Lord's Anointed (cf. 1 Sam 24:6), rejecting that sentence which came from the Apostolic See. Against him.

In the quoted passage from St Gregory, we find the logic of this submission: Athanasius was to be left ‘as seed and root to Israel, that Israel might again flourish and come to life with the infusion of the Spirit’. And the seed, to bear fruit, must accept death, like our Lord (cf. Jn 12:24). This is the highest testimony, the greatest and most fruitful work we have to do in this life. It is only faith that makes us believe that the acceptance of death (not only physical death), even for an unjust condemnation, is able to bear more fruit than any other work or foundation accomplished in the break with the successor of Peter.

We should never stop reading and re-reading this passage from John's Gospel: ‘But one of them, named Caiaphas, who was high priest in that year, said to them, ’You understand nothing and do not consider how it is better that one man should die for the people and the whole nation not perish. This, however, he did not say for himself, but being high priest he prophesied that Jesus should die for the nation, and not for the nation only, but also to gather together the children of God who were scattered’ (John 11: 49-52). This is a text of unimaginable depth. The death of the Lord, the most blasphemous act that men could perform, the act most constitutively contrary to the purpose for which the high priesthood had been instituted by God, was decreed by an authority that was profoundly iniquitous, but recognised as legitimate, to the point that from that mouth God did not disdain to draw the substantial prophecy that reveals the meaning of the Incarnation. An authority before which the Lord not only deigned to be judged, but to which he surrendered himself. He left us an example, so that we might follow in his footsteps (cf. 1Pt 2:21).

A profile of the next Pope, writes Cardinal

Two years after the text signed 'Demos' (later revealed to have been written by Cardinal Pell) a new anonymous document, linked to the first, defines the seven priorities of the next Conclave to repair the confusion and crisis created by this Pontificate.

- L'identikit del prossimo Papa (I) II "Retrato robot" del próximo Papa (ES) II L'identité du prochain pape (F) II Identität des nächsten Papstes (D) II Identyfikacja następnego papieża (PL)

Crisis generates schisms: also Monsignor Viganò goes his own way

The announced episcopal re-consecration marks a point of no return for Bishop Carlo Maria Viganò, former apostolic nuncio to the USA and great accuser of Pope Francis in the McCarrick scandal. After illicitly ordaining priests throughout Europe, he intends to make a monastic structure in Viterbo the centre of his movement. But, it’s a mistaken and unsuccessful response to the crisis of the Church.