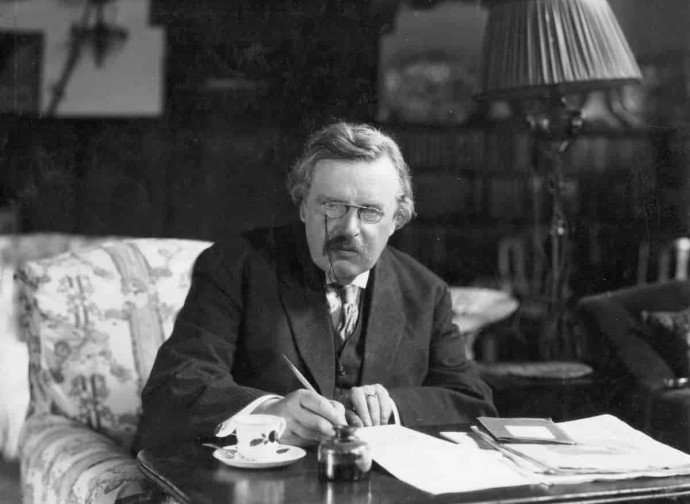

Chesterton turns 150, an antidote against rampant evil

On 29 May 1874, Gilbert Keith Chesterton, the great Catholic author who wrote the reasons for the Faith in his novels, was born in London. Today he is more relevant than ever, a real medicine for the soul.

One hundred and fifty years ago, on 29 May 1874, Gilbert Keith Chesterton was born in London, a brilliant author about whom not enough has been either said or written. Yet, a century and a half after his birth, Chesterton is more relevant than ever, with his defence of reason, with that masterly use of paradox that always characterised him. A paradox never an end in itself, not an intellectual game, but a method to awaken the mind and conscience.

Chesterton defended the beauty of Faith, the proclamation of Salvation that is a person: Jesus Christ. And he did it with passion, with decision, with sympathy, even. He was truly a Manalive, like the title of one of his famous novels. A Christian against the tide. And that is why after so many years he is still relevant: because the conflict between the Church and the World is taking on - in recent times - dramatic dimensions. When Chesterton was born, in 1874, London was the largest, most populous and important city in the world: the heart and mind of Western civilisation and the order it established. Chesterton's adolescence corresponds to the desperate, twilight years of symbolism and decadentism, of the nationalisms that led to the tragedy of the First World War and the totalitarianisms of the 20th century.

Faced with the spread of evil, Chesterton's work is a kind of medicine for the soul, or rather, more accurately, an antidote. The writer himself had actually used the metaphor of the antidote to indicate the effect of holiness on the world: the saint is meant to be a sign of contradiction and to restore sanity to a world gone mad. ‘Still each generation seeks by instinct its saint,’ he had said, ‘and he is not what people want, but rather the one whom people need... Hence the paradox of history that each generation is converted by the saint who contradicts it most. The way Chesterton succeeded in contradicting the generation of his time was by being happy. An authentic happiness, which to be such does not at all prescind from pain, toil and tears.

Reading Chesterton, abbreviated to GKC, whether novels or essays, always leaves the reader with a great serenity and a feeling of hope that springs not from an irenistic and worldly optimistic view of life (which is in fact the furthest thing from Chesterton's thought, which denounces in detail all the aberrations of modernity) but from the Christian, virile fortitude of religious experience. Chesterton's proposal is to take reality seriously in its entirety, starting with man's inner reality, and to confidently use the intellect - that is, common sense - in its original sanity, purified of all ideological encrustation.

Rarely does one read pages like his, in which he speaks of faith, conversion, doctrine, as clear and incisive as they are devoid of any sentimentalistic and moralistic excess. This derives from Chesterton's careful reading of reality, who knows that the most deleterious consequence of de-Christianisation has not been the serious ethical loss, but the loss of reason, which can be summed up in this judgement of his: ‘The modern world has suffered a mental collapse, much more substantial than the moral collapse’. Faced with this scenario, Chesterton chooses Catholicism, and affirms that there are at least ten thousand reasons to justify this choice, all valid and well-founded, but all traceable to a single reason: that Catholicism is true, the responsibility and the task of the Church therefore consist in this: in the courage to believe, first of all, and then to point out the roads that lead to nothingness or destruction, to a blind wall or prejudice. ‘The Church,’ says Chesterton, ‘defends mankind from its worst enemies, those ancient monsters, hideous devourers that are the old errors.’

Chesterton was neither a philosopher, nor a theologian, but he led readers to reflection through his stories. And among the stories he most cherished were the detective stories.

He defended the reasons for detective stories in one of his essays, The Defendant: ‘It is not true that vulgar people prefer mediocre literature to works of great merit, nor that they like detective stories because they are literature of the lowest order. (..) It must be acknowledged that many detective stories overflow with exceptional crimes, just like a Shakespeare play. (..) Not only is the detective story a perfectly legitimate art form, but it has certain definite and real advantages as an instrument of the public welfare.’ For Chesterton, the detective novel offers us a realistic insight into human life, and is based on the fact that ‘morality is the darkest and boldest of plots’.

He learned to love and appreciate Catholicism before its doctrinal content, for those qualities of humility, simplicity and intelligence that he placed in the character of the detective priest.

In Father Brown there is never complacency about his own achievements: there is sorrow for all the evil in the world, a serene sorrow mitigated by the three theological virtues that he embodies with simplicity: faith, which never fails and which he communicates and transmits with naturalness; hope, which animates his activity as priest and investigator, with the intention of saving the sinner, if not preventing sin; charity, that is, love, the ability to offer God's forgiveness, the desire to see not the death (or punishment) of the guilty, but their conversion.

‘The Church rejuvenates while the world grows old.’ So wrote Chesterton in one of his essays, noting that Christianity is a madness that heals while the whole world goes mad. What makes the Faith always young and attractive is the fact that Christ has given us a more reasonable way of living, more lucid and balanced in its judgments, healthier in its instincts, happier and more serene in the face of fate and death.