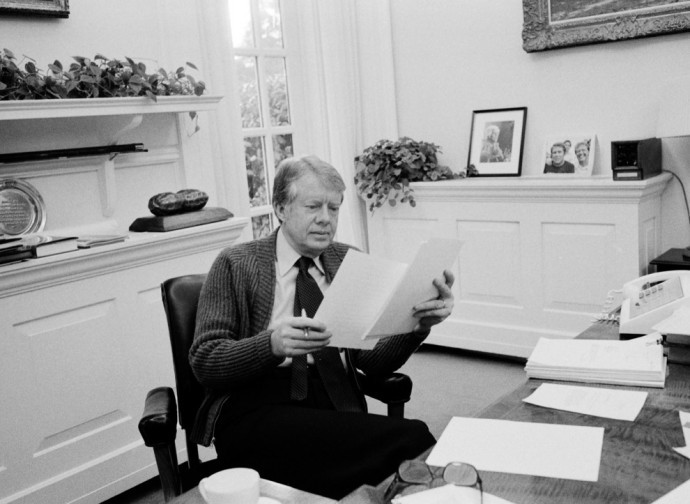

Carter, the president who launched the new left, dies at 100

James Earl 'Jimmy' Carter has died after a long illness. Remembered for his diplomatic triumph, the Camp David Accords, he failed to be re-elected to a second term due to the revolution in Iran. He led the American left towards a post-Christian vision.

Former President James Earl 'Jimmy' Carter has died at the age of 100 after a protracted illness and with his last wish half fulfilled. He wanted to live long enough to vote for Kamala Harris in the November elections and witness the victory of America’s first woman president. He made it to vote, but his hopes were dashed when the Democratic candidate lost to Donald Trump. Carter died 22 days before the inauguration of the new Republican president.

Carter was the longest tenant of the White House. His presidency coincided with the worst foreign policy crisis in the United States and a severe economic crisis. Despite some historic successes, such as the peace between Egypt and Israel negotiated under his auspices at Camp David, he was also associated with several serious defeats, notably the failed attempt to free US hostages in Tehran, and lost re-election in 1980. Living his Baptist faith as a mature Christian, he marked more than others the Democratic Party's transition from a Christian to a post-Christian vision, embracing all the 'new rights'.

A former Democratic governor of Georgia, Carter was elected the 39th president of the United States in 1976, at a critical time in American history. Two years earlier, Richard Nixon had been forced to resign in the wake of the Watergate scandal (he was accused of spying on the 1972 Democratic convention). A year earlier, in April 1975, communist North Vietnam had completed its conquest of the south, ending a ten-year war in which the Americans had lost over 50,000 men in a failed attempt to defend the government in Saigon. Since 1973, the OPEC (Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries) oil strike, organised to force the US and European governments to withdraw their support for Israel after the Yom Kippur War, had triggered a spiral of recession and inflation. Carter inherited all these problems, but only solved a small part of them, due to the unfortunate international conjuncture, but also to his own weak management.

The economic crisis was tackled with a welfarist approach, notably a $30 billion stimulus package. After a recovery in the first two years, the crisis returned with a vengeance at the end of the 1970s, with double-digit inflation and a return to recession. The international crises in the Gulf and rising prices by Opec were blamed, but also a very expansionary fiscal policy and strong monetary expansion by the Fed. In 1980, when Americans were asked the fateful election question "Are you better off today than you were four years ago?", the answer was a resounding no.

Foreign policy was the workhorse of the 39th US president, who went down in history as the man who negotiated the Camp David peace agreement between Egypt and Israel, ending thirty years of hostility. Despite all the vicissitudes that followed (two wars in Lebanon, two Palestinian uprisings, two revolutions in Egypt and the ongoing war in Gaza), that peace still holds today.

However, there were many setbacks that made Carter a 'weak' president in the eyes of Americans. Firstly, the Cold War entered a new critical phase and the USSR continued to expand throughout his term, with military interventions in Angola, Ethiopia, Mozambique and Yemen, support for the revolutions in El Salvador and Nicaragua, the deployment of SS-20 medium-range missiles in Europe and, finally, the devastating invasion of Afghanistan in December 1979. Carter inherited from his predecessors Nixon and Ford a policy of détente with the Soviet Union aimed at bilateral nuclear disarmament. But he ended his presidency with a resumption of tensions in what became known as the 'Second Cold War'.

As a Democratic president and heir to Kennedy's 'new frontier', Carter focused on respect for human rights, starting with the Helsinki Accords with the Eastern bloc, signed by his predecessor Ford in 1975. The agreements, which were not legally binding, recognised the 1945 borders, including the division of Germany and the annexation of the Baltic states by the USSR. But they also provided for a controlled protection of human rights in the Eastern bloc. From the first year of Carter's presidency, however, the Soviet regime, with Brezhnev as president, intensified its repression of dissent. The Jewish refusenik Anatoly Sharansky was arrested in 1977, and the dissident physicist Sakharov was imprisoned in Gorky in January 1980 (for demonstrating against the invasion of Afghanistan), having been denied the right to collect the Nobel Peace Prize. The human rights treaty turned out to be a sham; every US protest was met by the Brezhnev regime's claim that it was an 'internal affair'.

The worst defeat, however, came from Iran, a traditional US ally in the Persian Gulf. A revolution that the regime of the Shah of Persia failed to manage, confining itself to unleashing brutal violence against its opponents, led to the overthrow of the monarchy. At the decisive stage, Carter, in the name of democracy, sacked his monarchist ally and facilitated his flight from the country. But it was not democracy that replaced the monarchy, but (after a very short interregnum) the far more repressive Islamic regime led by Ayatollah Khomeini: the Islamic Republic, which is still in power today. In order to facilitate the establishment of the new regime, the Iranian Revolutionary Guards stormed the US Embassy in Tehran and took the entire staff hostage. After diplomacy failed, Carter authorised a show of force, an attempt to free the hostages with a naval raid. The attempt failed miserably in April 1980, with the destruction of four helicopters, one plane and eight dead. All without ever striking the enemy. It was a humiliation that cost Carter dearly in an election year.

In November of that year, Ronald Reagan won, promising to restore US prestige in the world, defeat the Soviet Union and revive the American economy. All these goals were achieved in Reagan's two terms, relegating Carter to the historical role of a weak and defeated president.

After his time in the White House, however, Carter's political activity did not end. He reinvented himself as an ambassador for peace, on behalf of the Clinton administration and then with a group of former world leaders called 'The Elders'. However, it is difficult to find any successes in the peace and mediation work, albeit meritorious, of post-president Carter. In 1994, in an attempt to end the military crisis between North and South Korea, he made the mistake of allowing the then dictator Kim Il-sung to bring home a nuclear deal that allowed his successor Kim Jong-il to develop the atomic weapon over the next ten years. He travelled the world, from Sudan to Syria, from Cyprus to Zimbabwe, but in none of these countries did he succeed in ending conflict or human rights abuses. However, his personal diplomacy won him the Nobel Peace Prize in 2002. He was then mentored (in confidence) by another Nobel Peace Prize winner: Barack Obama.

It would be an exaggeration to call Carter a post-Christian president: he remained a Southern Baptist all his life. But he paved the way for the transformation of the Democratic Party. During his presidency, he opposed abortion but implemented the Roe vs. Wade ruling that legalised it nationwide. In the 2000s, long after his presidency, he wrote a book in support of abortion rights, demonstrating his personal commitment to the cause. In 2000, he broke with his Southern Baptist church over its refusal to allow women to be pastors, and in the years that followed he campaigned for women's equality in the church. When the debate about gay marriage arose, Carter was immediately in favour. Even Jesus would be for it," he wrote in one of his editorials on same-sex marriage. He was a mentor to Obama, who began to introduce sexual 'new rights' as fundamental principles. For this, Carter can be remembered as the president who led the American left into a post-Christian vision.