Bread, symbol of life

Today we begin a long journey into food in biblical times. Food in general and meals in particular play an important role in human history and thus in biblical history. We will start with bread, food par excellence: it is mentioned 361 times in the Bible, and Jesus himself self-identifies with bread.

- THE RECIPE: CHEESE-FILLED BREAD

Go, eat your bread with joy,

And drink your wine with a merry heart;

For God has already accepted your works.

(Ecclesiastes 9:7)

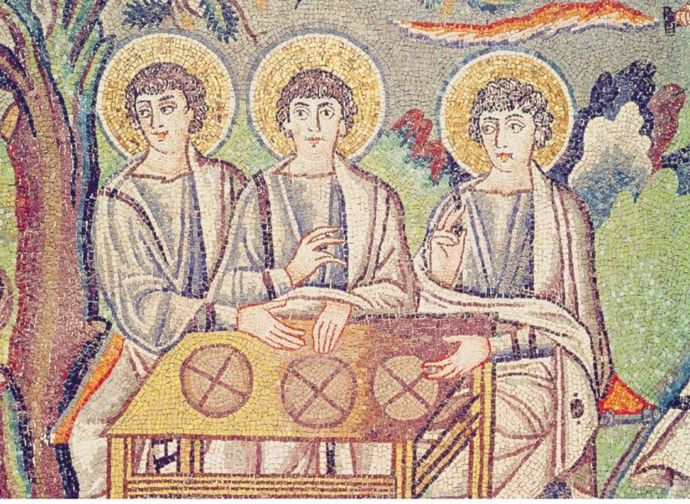

(Pictured above: The three angels, detail of ‘The Hospitality of Abraham’, 5th century mosaic, Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna).

With this article today we begin a long journey, full of interesting discoveries and reflections. We will read, through the verses, the history of food in biblical times. We will also visit the habits of the peoples who preceded the time of Jesus.

Food in general, and meals in particular, play an important role in human history and thus in the biblical story. From the fruit picked by Adam and Eve (the Bible never says it was an apple) to the Eucharistic meal, the manna in the desert, and the wedding banquet at Cana: many decisive moments are played out around a meal.

On several occasions, we find Jesus sharing a meal with very different people: Lazarus’ family, a Pharisee, publicans, Zacchaeus, and even with sinners. This last category of diners was at the centre of much friction between Jesus and the priests of his people (Mark 2:13-17, Matthew 11:18-19).

Our journey will begin with the staple food: bread, which is mentioned 361 times in the Bible. Note that the account of the multiplication of the loaves (and fishes) and the huge meal that follows is the most frequent text in the four Gospels, since we find no less than six narrations: two in Matthew, two in Mark, one in Luke and one in John.

A simple and modest food, bread was a dietary staple, known for a long time in the Middle East. Bread has accompanied mankind since the dawn of time; it is a symbol of life at all latitudes, in all centuries, and in all languages. In Hebrew, ‘to eat his bread’ meant ‘to partake of a meal’.

A simple and modest food, bread was a dietary staple, known for a long time in the Middle East. Bread has accompanied mankind since the dawn of time; it is a symbol of life at all latitudes, in all centuries, and in all languages. In Hebrew, ‘to eat his bread’ meant ‘to partake of a meal’.

It was therefore necessary to treat bread with respect: although hardened bread was sometimes used as a plate, it was forbidden, for example, to put raw meat or a jug on the bread or to place a hot plate next to it. It was even more forbidden to throw it away: crumbs ‘the size of an olive’ had to be picked up and eaten. Bread was not cut: it was broken. Let’s remember the words of the Mass: “Jesus took bread, blessed and broke it” (Matthew 26:26).

Jesus is often symbolic of bread and He Himself self-identifies with bread:

“This is the bread which came down from heaven: not as your fathers ate the manna, and are dead. He who eats this bread will live forever.” (John 6:58). / “This is my body which is given for you; do this in remembrance of me” (Luke 22:19).

Moreover, let us not forget that Jesus was born in Bethlehem, the city of David, which etymologically in Hebrew means “house of bread” (בֵּיִת לֶחֶם, Beit Leḥem). He is swaddled and placed “in a manger”, Saint Luke specifies (2:7). A very important detail: the child Jesus is the one who will be called “the bread of life” (John 6:35).

To emphasize the symbolism of the bread identified with the person of Jesus: those who prepare the wafers make incisions in the dough. The inscriptions reproduce the letters IHS which are the first three capital letters of the Greek name Iesous. Others read IHS as an acronym for the Latin Iesus Hominum Salvator (Jesus Saviour of mankind), which in this form has the same meaning. The host is unleavened bread, which is the subject of much biblical and theological discussion, but we do not have the space to discuss it here. As a reading, I recommend Exodus 12:1-51, which gives an overview of the subject.

To emphasize the symbolism of the bread identified with the person of Jesus: those who prepare the wafers make incisions in the dough. The inscriptions reproduce the letters IHS which are the first three capital letters of the Greek name Iesous. Others read IHS as an acronym for the Latin Iesus Hominum Salvator (Jesus Saviour of mankind), which in this form has the same meaning. The host is unleavened bread, which is the subject of much biblical and theological discussion, but we do not have the space to discuss it here. As a reading, I recommend Exodus 12:1-51, which gives an overview of the subject.

In the biblical world, bread was not the same for everyone: the poor ate barley bread, the rich ate wheat bread, always ground between two millstones, a job usually carried out by women. The grains of wheat were also roasted and served as a garnish for meat: somewhat coarsely ground, it produced the equivalent of polenta or couscous. This method was used even earlier, in ancient Egypt, as it was frequently eaten with cheese, either as a filling or separately, or used in the bread dough itself.

Bread filled with cheese (see recipe in the linked article) is a substantial dish with a very ancient history. The Romans already prepared it more than two thousand years ago, accompanying it with honey and fresh figs. The ancient Egyptians also loved bread filled with soft cheese and honey. The ancient Greeks had their own variation, a simple loaf of bread filled with feta cheese.

And although it is an ancient dish, it also lends itself very well to modern palates.

In France, there is bread with Gruyère, a dish that originated in Switzerland (canton of Fribourg) and was ‘transferred’ to Savoy; in Italy, it is typical of various regions (Campania, Tuscany, South Tyrol, Veneto); in Germany, the bread is filled with cheese and caraway seeds; in the Balkans, cheese is mixed with onion and black pepper and this composition is used to make a bread similar to Greek pita; in Alsace, bread filled with cheese is brushed with goose fat.

The variations, from one country to another, lie in the variety of fat used (butter, olive oil, lard, or duck fat), flour (cassava, wheat) and cheese: gruyère, parmesan, mozzarella, ricotta, feta or suluguni in Georgia (Caucasus).

In this case too, and once again, food is an element of continuity, linking human beings, places and eras. While characterising each of these realities (time, nations, territories), there is a common thread in the transmission of culinary tradition that gives it a divine value, due to its timelessness, which in some way brings it closer to God. Food is, for most religions, not only a product, but a value: yesterday as today, the faithful recognise in eating and drinking actions charged with a strong religious significance. Even ‘no-food’ - abstinence and fasting - are characteristics that religions have in common.

Like the consumption of food, the renunciation of food also has a sacred value, which is often also communal: in addition to sharing meals, the faithful observe a time of fasting together, in which attention is paid to the sacred and to belonging to a community in everyday life.

In addition, one must be aware that food is a gift that many do not have; feeling hunger can help us to be more generous towards those who cannot afford even one meal a day.

And at this time of year, more than ever, we must act accordingly: it is a tribute to God and to our humanity.