Abu Dhabi, one year later: The ambiguity about religions remains

One year after the signing of the Abu Dhabi Declaration, two fundamental ambiguities remain: the will of God regarding the plurality of religions and the way in which religions ought to collaborate for peace. But the point is this: the way in which religions see God determines the way they see the human person, the family, woman, law, and freedom, as well as peace.

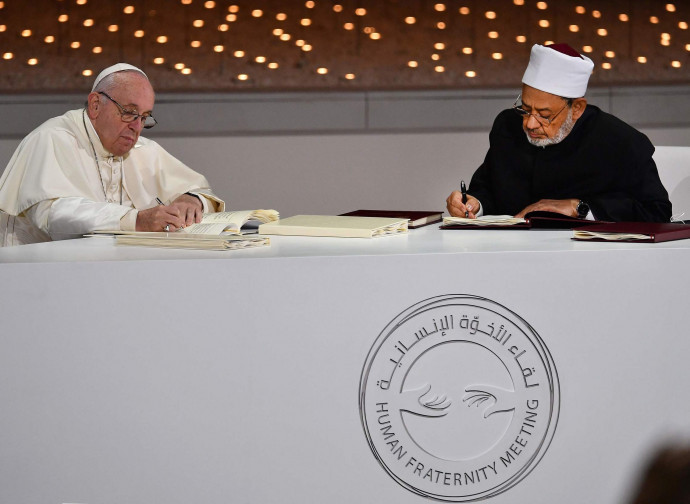

One year ago, on February 4, 2019, the now famous so-called “Abu Dhabi Declaration on Human Fraternity for World Peace and Living Together” was signed. The document bears the signatures of His Holiness Pope Francis and the Grand Imam of Al-Azhar Ahmad Al-Tayyeb, which were placed on it at the conclusion of the inter-religious meeting at the Founder’s Memorial of Abu Dhabi during the apostolic journey of Pope Francis to the United Arab Emirates from February 3-5, 2019. Following this signing and in continuity with it, the Committee on the Declaration on Human Fraternity was created. Last December this committee filed a proposal with the Secretary-General of the United Nations on behalf of Catholics and Muslims, asking that February 4 be declared “World Day of Human Fraternity.” This coming May 14, Pope Francis has called a world meeting at the Vatican entitled “Reinventing the Global Educational Alliance” which will teach about “universal solidarity” and a “new humanism.”

The signing of the Abu Dhabi Document and the program which follows it has enthused many and deeply worried others. The text of the document presents two points that are very problematic, both from the doctrinal as well as the pastoral point of view. The first is the statement: “The pluralism and the diversity of religions, colour, sex, race and language are willed by God in His wisdom.” Further clarifications made by Pope Francis saying that the statement referred to the “permissive” will of God were not sufficient to mend the doctrinal rift the statement contains. If God wills all the different religions, then they are all indispensable for salvation, Christ is no longer the One Universal Savior, and people who follow other religions do not need to be evangelised.

The second ambiguity concerns the collaboration between religions for peace and common coexistence. The Catholic Church may certainly propose a fraternity between all people and a common coexistence, based either on the natural law or on the truth of Christ. On the natural level we are all human beings, and we carry a moral law in our human nature that guides our common life. Leveraging this natural unity of the human race is a positive thing, even if the Christian knows it is not enough, since nature without grace will end by deteriorating, as is seen in nature. But basing collaboration for unity and common coexistence on religions is very problematic, because not all religions respect the natural law, either in whole or in part, and also because, obviously, not all religions accept Christ and the purification of the natural law which He has accomplished. The compass that guides the Catholic Church when it speaks about peace and human coexistence is twofold: first, the natural law which is a result of creation and known by right reason, and secondly the salvation brought about by Christ. In the Abu Dhabi Document neither one of these is present: Catholic and Muslims think very differently about the natural law, and even more differently about Christ.

From the Catholic point of view, there is an ambiguity in the Abu Dhabi Document: it maintains that it is possible to agree with all other religions, if not on doctrinal aspects, then on practical ones such as peace, tolerance, religious freedom, respect for the dignity of woman, the protection of minorities, and so forth. Such a pretext, however, has no foundation, because doctrinal questions are not only doctrinal and do not exist only in an abstract heaven without any connection to practical questions.

The vision that religions have of the face of God determines their visions of the human person, the family, woman, law, freedom, politics, authority, the common good...each of which has a very different definition in different religions. For example, there is no small divergence between the Catholic vision and the Muslim vision on these topics we have listed here. It is strange to maintain the salvific unicity of Christ, the unicity of the call to salvation, the necessity of coherence in the life of a Catholic between the faith that he professes and his behaviour…and at the same time to support a worldwide convergence of all religions. If the Church does not want to propose a convergence based on Christianity then it should propose a convergence based on natural law, knowing however from the outset that not all religions will be able to join such a union.

These observations make us understand that the fear of going down a path towards a generic universalist post-religious humanism is not unfounded. What will be the basis for the “Educational Alliance” and the “New Humanism” if not the natural law or Jesus Christ? Education always serves a certain purpose, and what will this purpose be if it is neither the natural law nor Jesus Christ? How can the “new human coexistence” be prevented from being based on the lowest common denominator and on a forced elimination of all of the “rough edges” of different religious identities, in order to construct an artificial Decalogue that will be imposed on a planetary level by those with the power to do so?